31.2Bicycle Infrastructure

The bicycle is the most civilized conveyance known to man. Other forms of transport grow daily more nightmarish. Only the bicycle remains pure in heart.Iris Murdoch, author and philosopher, 1919–1999

This section focuses on the design and operation of bicycle facilities—bike lanes, greenways, or low-speed streets—along BRT corridors and the infrastructure required for a successful bicycle network, namely parking and riding facilities. A BRT corridor is an ideal place to construct a bike lane. The primary reason is that the corridor is typically designed to facilitate through traffic; turns are banned, signals are timed to give priority to the BRT vehicles, and so on. Cyclists can benefit greatly from this. A second reason is that the BRT corridor can double as a spine of the bicycle network, especially if none exists. Lastly, co-joining the bike and BRT routes helps to integrate service. A cyclist riding to the BRT station may enter the corridor at a number of points, then ride along the corridor to the station. He or she might choose to bypass a local or crowded station in favor of an express station. BRT lines in Los Angeles; Eindhoven, Netherlands; Cape Town, South Africa; Delhi, India; and Guangzhou, China, all have parallel bicycle facilities.

31.2.1Bicycle Infrastructure Planning

Collecting information about existing cycling activity and cyclist behavior is a useful first step before designing cycling facilities. Methodologies for doing this are roughly equivalent to methodologies for designing pedestrian facilities, starting with a review of existing cycling facilities, the identification of locations dangerous or illegal for cyclists to operate, mapping of popular cyclist routes, major origin and destination locations, identifying major severance problems, reviewing data about locations of high levels of cycling crashes, and targeting interventions to these locations. Engaging the public can identify unsafe cycling environments and preferred routes.

A few simple rules should be considered when planning cycling facilities:

- Cyclists are more sensitive to road surfaces than motorists, and prefer smooth surfaces. Cobblestones and rough brick may be aesthetically pleasing, but such surfaces can discourage cycling;

- Cyclists want to go straight. Cyclists want to get where they are going as fast as anybody else, and do not want to have to meander around trees and park benches;

- Cyclists will not use substandard, poorly maintained, obstructed, narrow bike lanes unless they must. Build high-quality bike lanes, greenways, off-street paths, or redesign the road for safe mixed bicycle and motorized vehicle traffic operation;

- Having a large vehicle bearing down upon a cyclist can be quite stressful. Stress-free cycling facilities encourage higher ridership, especially among women, older adults, families, and youth. Relocating buses into the central median resolves one of the most pressing conflicts faced daily by cyclists.

31.2.2Bicycle Infrastructure Financing

Ideally, bicycle infrastructure, including parking, is seen as an integral part of an intermodal public transport system. Bicycles can substitute, augment, and expand the public transport network at little or no cost to the public transport agency. Nevertheless, there are a number of opportunities to finance bicycle parking:

- Advertising;

- Retail concessions in exchange for providing security, maintenance, and service;

- Public-private business partnerships;

- Sponsorship by public-health organization seeking to increase fitness;

- Cross-subsidies from auto-parking fees, congestion charging, and fuel taxes;

- Conversion of underutilized auto parking (ten bike parking spaces equal one auto parking space).

31.2.3Design of Bicycle Facilities on BRT Corridors

BRT corridors tend to be located on reasonably wide primary or secondary urban arterials. In developing countries, which frequently lack a strong secondary road network, these arterials often serve a great diversity of trip types and modes, from intercity bus and truck trips, to medium- and long-distance intercity public transport trips, to short-distance cycling and walking trips. This complex multifunctionality of a BRT corridor makes road design reasonably difficult. As the lane widths and the number of lanes increase, vehicle speeds tend to increase, and hence the desirability of segregating modes of significantly different operating speeds increases.

Just like motorists on such an arterial, some cyclists are going longer distances and value uninterrupted higher-speed travel over access, while others are only going a short distance and value access to adjacent properties over speed. For motorists on such arterials, this conflict is frequently resolved by providing separate through lanes for long-distance vehicle travel and service lanes for property access. Adding BRT on such an arterial into the central road verge introduces no particular problems for motorists. Excluding bike lanes, the standard cross section would have bus lanes in the median, then higher-speed traffic lanes, a side median, a service lane for local-access trips, and then a walkway on the outside.

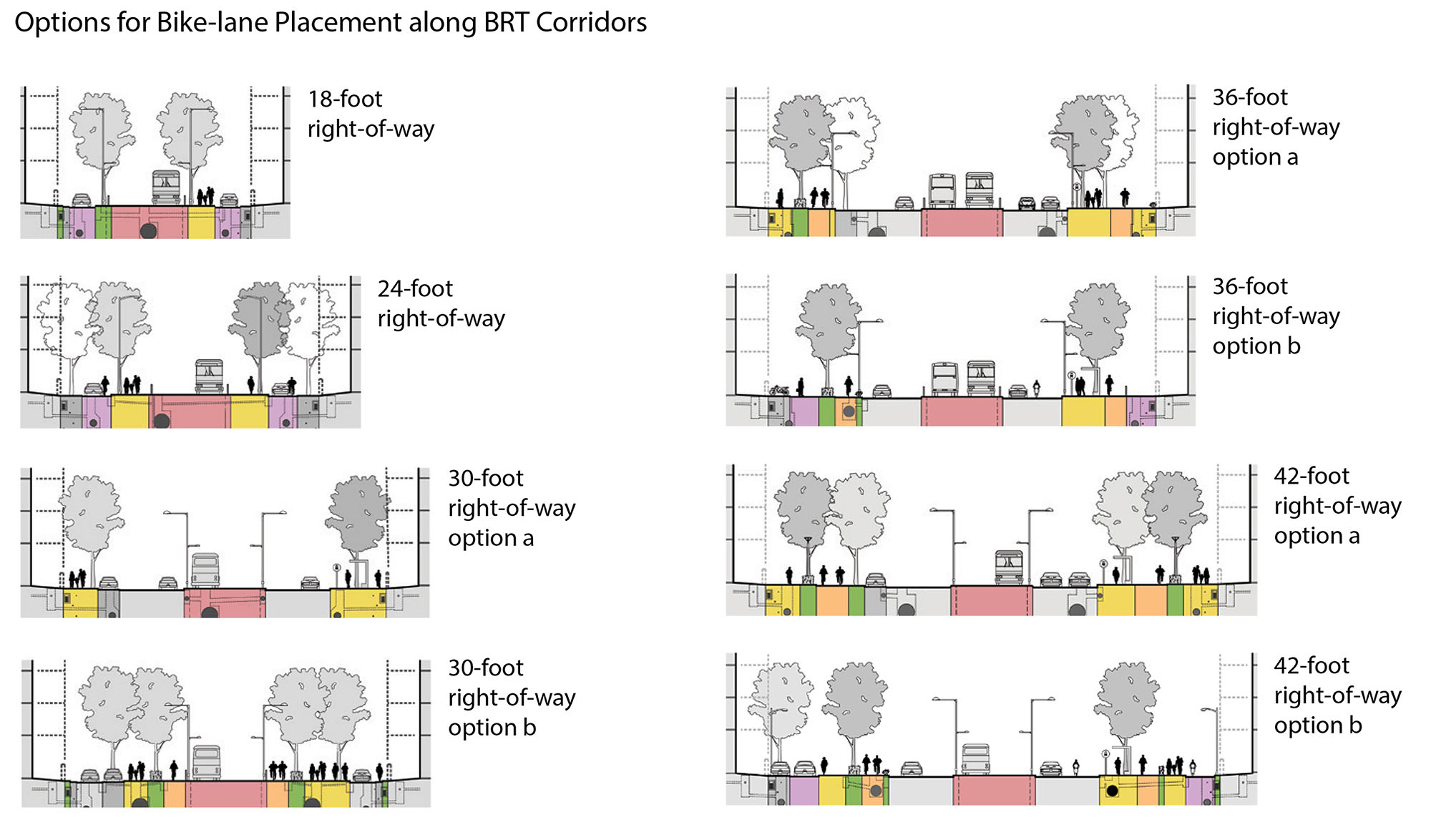

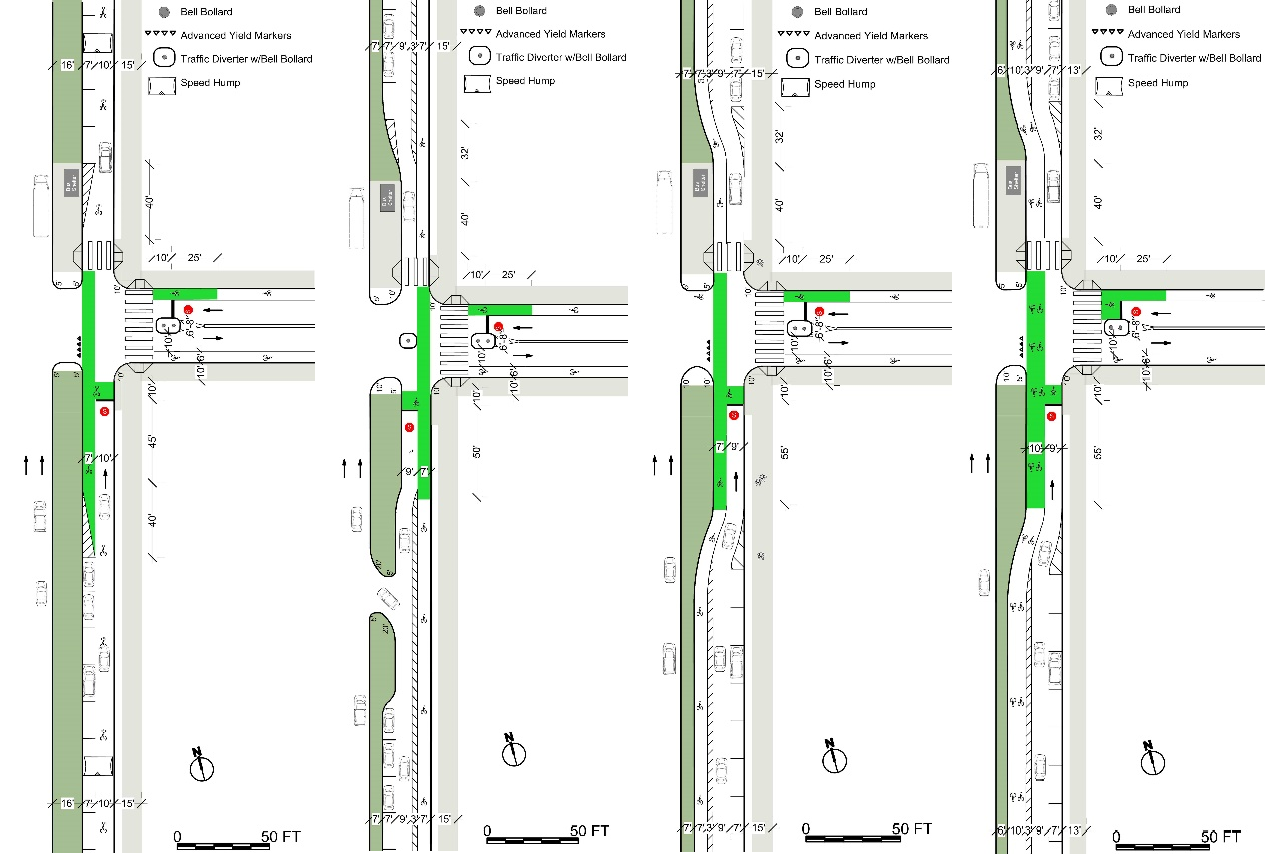

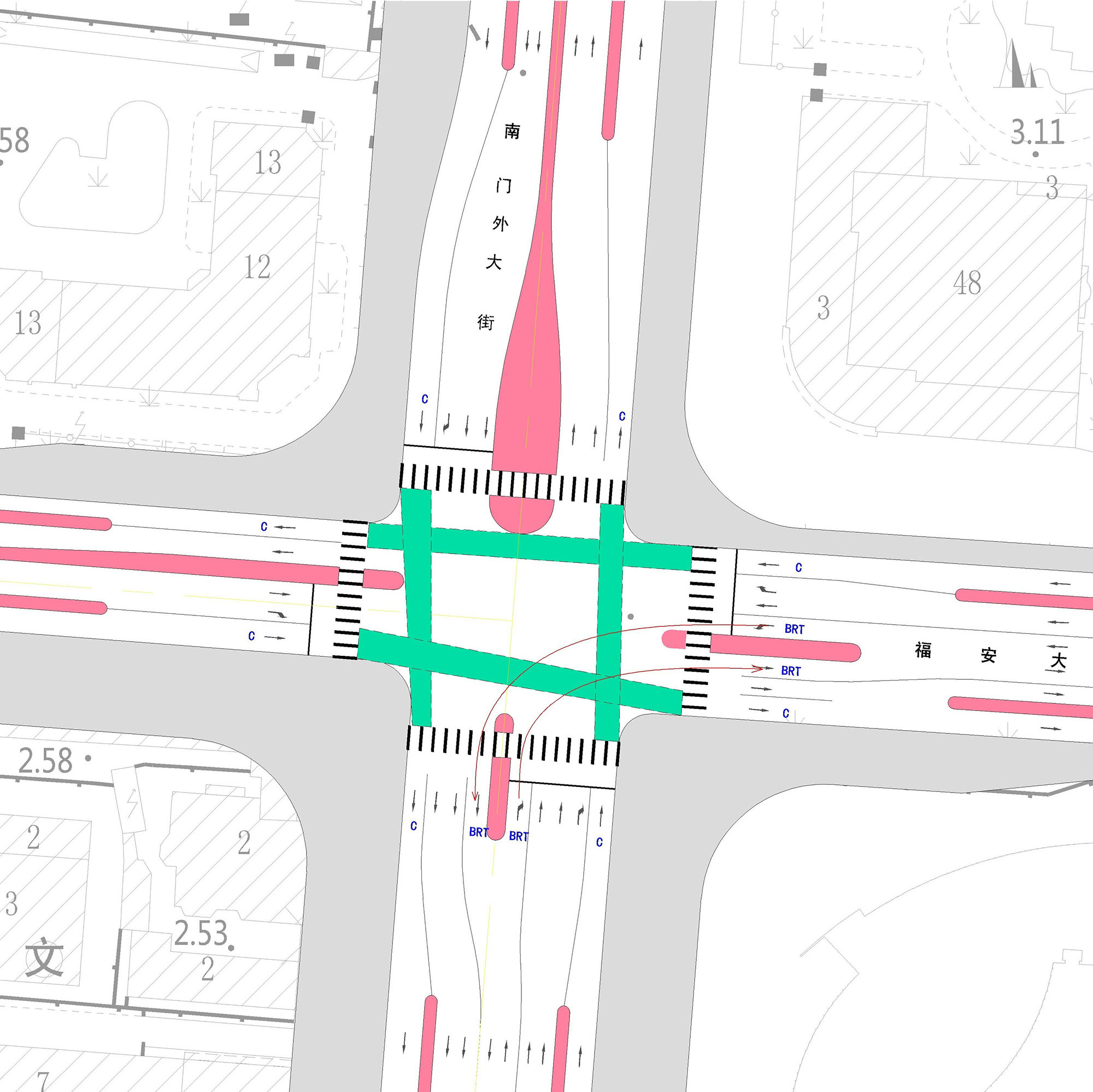

Generally, bicycle facilities are placed in the side median or service lane. The exact location and type of the facility (bike lane, shared street, etc.) depends on a number of factors, including the amount of space available, volume and speed of motorized traffic, number and location of cross streets and driveways, amount of bicycle traffic, and parking, among others. The images in Figure 31.12 and Figure 31.13 illustrate various options.

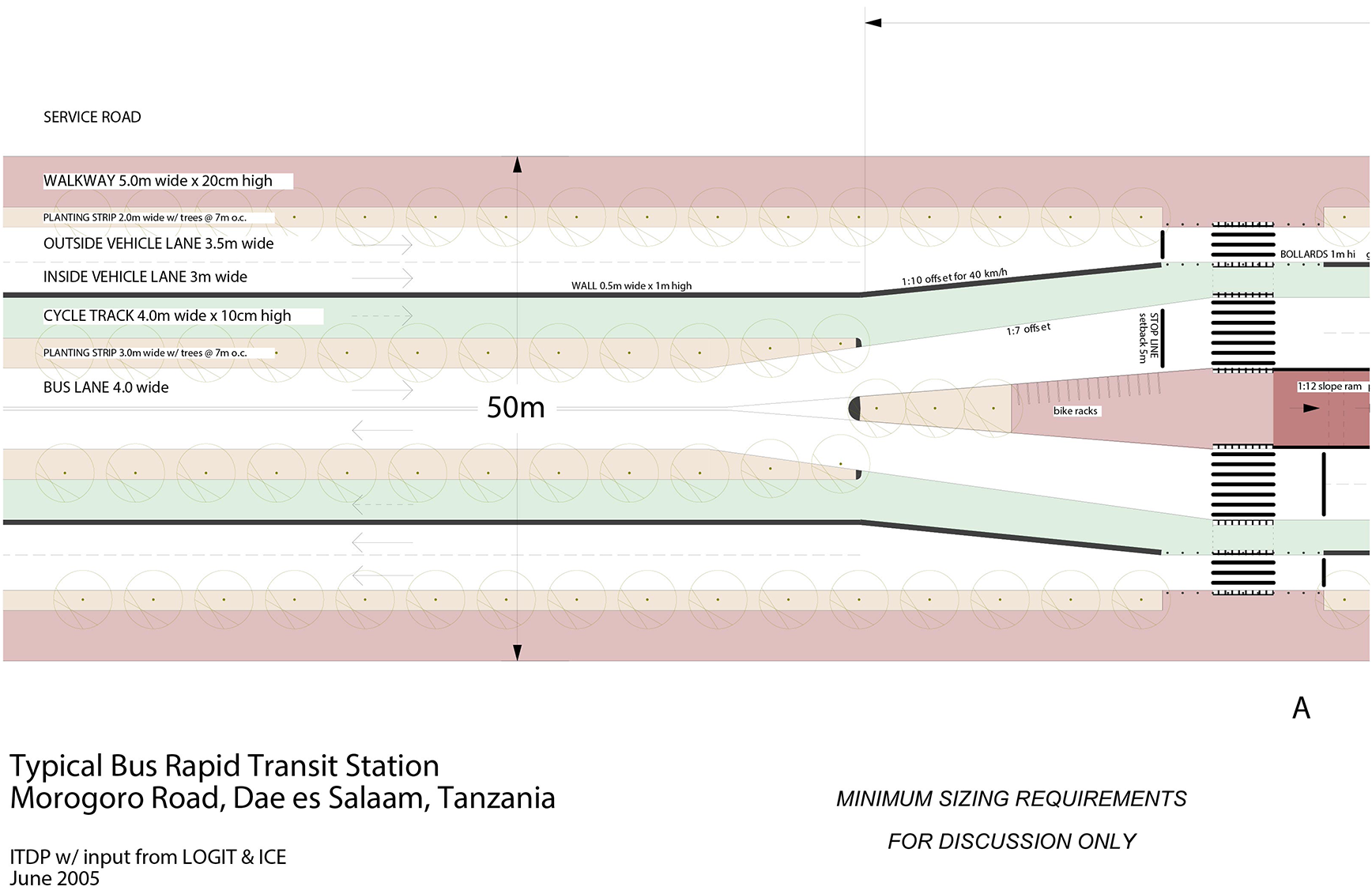

31.2.3.1Bike Lane in the Central Median

Another configuration is to give cyclists the same advantages that buses enjoy from central-lane operation: priority at intersections. Here, the bike lane is integrated along with the BRT in the central median. Accommodations must be made at the stations (to allow customers to access the stations), at U-turns, and at intersections. Signal priority is generally given to cyclists so that they can turn ahead of motorists.

This configuration removes many of the turning conflicts between bicycles going straight, and turning and stopping vehicles. It significantly reduces the risk of encroachments into the bike lane by street vendors. It provides a very high-speed cycling corridor. Bicyclists wanting to make local-access trips would simply exit the bike lane at the intersection or pedestrian crosswalk closest to their destination, and use the service lane or sidewalk for the remaining distance.

31.2.3.2Bicycle Facilities at Intersections

Wherever the bicycle facility is placed, its treatment at intersections is crucial. The basic principles to consider include:

- Reduce auto speeds, especially turning speeds;

- Highlight bike facilities via markings, signs, and lights;

- Provide mixing and merge zones so that drivers and cyclists may interact with each other at low speeds;

- End visual obstructions before the intersections, so that drivers, cyclists, and walkers may have good visibility;

- Give preference to cyclists over motorized traffic via signals and advance stop lines;

- Provide road space for queued cyclists.

31.2.4BRT Corridors without Bicycle Facilities

If no cycling facilities are provided, the likelihood of bicyclists using the busway as a bikeway is fairly high. Cyclists take advantage of the limited cross-traffic, favorable signal progression, and separation from auto traffic. This has led to serious bus-bike crashes in BRT corridors, especially along hilly corridors. As a matter of safety, it is preferable to either construct bike lanes within BRT corridors or design the busway such that BRT drivers can safety pass cyclists. Additionally, cities should develop strategies for enforcing lane violations, without discouraging cycling. Informational ticketing, public information campaigns, and using mascots or other humorous tactics are all positive means of enforcement and education.

31.2.5Types of Bicycle Parking

Bicycle parking ranges from a simple rack to a bike station, where you can park your bike, have it repaired, and take a shower. The best type of bicycle parking is indoors, in a secure location. Yet, like cars, bikes are often parked on the street, as close to the BRT station as possible. Parking types are defined and compared below.

31.2.5.1Bike Racks

Bike racks are the most abundant type of parking facility and generally the least expensive to install. Spatially, they are the most efficient and can accommodate the greatest number of bicycles. There are many different styles and forms of racks. The most effective racks:

- Support the bicycle while locked. The rack design should hold the bicycle upright while locked, without it falling or being able to be knocked over. It should also be oriented to allow sufficient access when locking the bicycle;

- Are immovable. Racks should not be able to be lifted, dragged, or removed from the site. They should be firmly secured or permanently installed;

- Accommodate locking both wheels. Racks that only hold one wheel require users to remove a wheel to lock it or risk having it stolen;

- Have no moving parts. These break and require maintenance.

31.2.5.2Bicycle Lockers

Bicycle lockers provide a higher level of security than racks and protect bikes from weather. Users can also sometimes store clothing, helmets, and other bicycle accessories in lockers. Access to lockers varies, from single-key individual long-term use, to electronic card locks that allow for multiple users over an extended time period. Lockers are made of a variety of materials, including fiberglass, plastic, and steel.

In some areas, problems have been encountered with lockers being used for unintended purposes—for storage of items other than bicycles, or even people sleeping in them. These abuses can be prevented by using lockers with openings, which can also facilitate periodic cleaning.

31.2.5.3Shelters and Garages

Shelters generally consist of rows of bicycle racks protected underneath a structure that is either fully or partially enclosed. Shelters and garages require more space than racks or lockers and have higher installation and maintenance costs, but provide a significantly higher level of security. If a sufficient number of cyclists are utilizing the station, it may be economically viable to offer a formal cycle storage area with a permanent attendant. This also allows for a valet system in which the bicycle can only be taken by providing the appropriate “claim ticket.”

31.2.5.4Bicycle Stations

A bicycle station is a combination of a bicycle repair shop, paid parking, and dressing facilities. There are a number of configurations, including being paired with gyms, bicycle rental, and retail opportunities.

Table 31.2Comparison of Bicycle Parking Facilities

| Facility type | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Bicycle Racks |

|

|

| Bicycle Lockers |

|

|

| Bicycle Shelters and garages |

|

|

| Bicycle Stations |

|

|

31.2.6Bicycle Parking at BRT Stations

The challenge with bicycle parking facilities for BRT systems usually relates to the space available. For BRT stations located in the median of the roadway, space may be available in front of or behind the station structure. Underneath the entry ramp of a pedestrian bridge may also be a possibility. Alternatively, bicycle parking could be provided adjacent to the station, on the side of the road. At terminal sites, BRT systems typically have sufficient space to provide a higher-quality parking area for bicycles. In all cases, the security of the bicycle becomes an overriding consideration in order to encourage confident use.

31.2.6.1Case Study: Bogotá, Colombia

When the Bogotá BRT system was originally planned, the bicycle network was seen as a separate system from the BRT. By the time the Avenida Americas terminal was built, cycling integration was clearly on the agenda. A covered, guarded, eight-hundred-space bicycle parking facility was built at the terminal, and bicycle users could leave their bicycles at no additional cost. A 4 percent increase in BRT ridership has been attributed to the addition of this facility. To date, no bicycle has been stolen. The increase in bicycle connections to BRT has also reduced the need for feeder vehicles to the terminal. Following this success, bicycle parking was implemented in most terminal stations.

31.2.6.2Case Study: Guangzhou, China

The system in Guangzhou, China, has bicycle-parking stations at every BRT station, and the facilities include double-decker bicycle-parking infrastructure. After a rigorous study of current and future bicycle parking demand, the system planners built 5,500 covered bicycle parking spaces (3,500 covered and double-decker, 2,000 single with roof). This is the largest bicycle-parking integration in a BRT system in the world.

31.2.6.3Bicycle Parking away from the BRT Station

Besides being provided at stations, bicycle parking can be required in building, zoning, and development codes. This will increase the overall supply of parking, which is important because parking should be at one’s origin and destination, not just at the BRT station.

31.2.7Operations and Management of Bicycle Parking

When bicycle parking is considered in BRT systems, there is the question of who will operate and manage it. In general, the three main options are: 1) Include bicycle parking as part of the overall BRT management; 2) Place bicycle parking with another government agency; or 3) Outsource bicycle parking to a private company.

It is beneficial to include bicycle parking within the responsibilities of the BRT management agency. The primary reason is that this agency has a better chance to accurately compare the costs of bikes versus public transport service (bike is much cheaper). Introducing an external party tends to duplicate certain costs (personnel, marketing, fare collection), and tends to bias the decision-making process. At the end of the day the consumer is key, and whether he or she rides a bike or the bus is immaterial.

31.2.7.1Bicycle Parking Fees

Where the BRT system wants to encourage cycling, bike parking should be free. If there is a need to charge additional fees, these should be included in the cost of the fare. For example, one could offer a combined monthly BRT and parking pass.

31.2.7.2Bicycle Parking Publicity

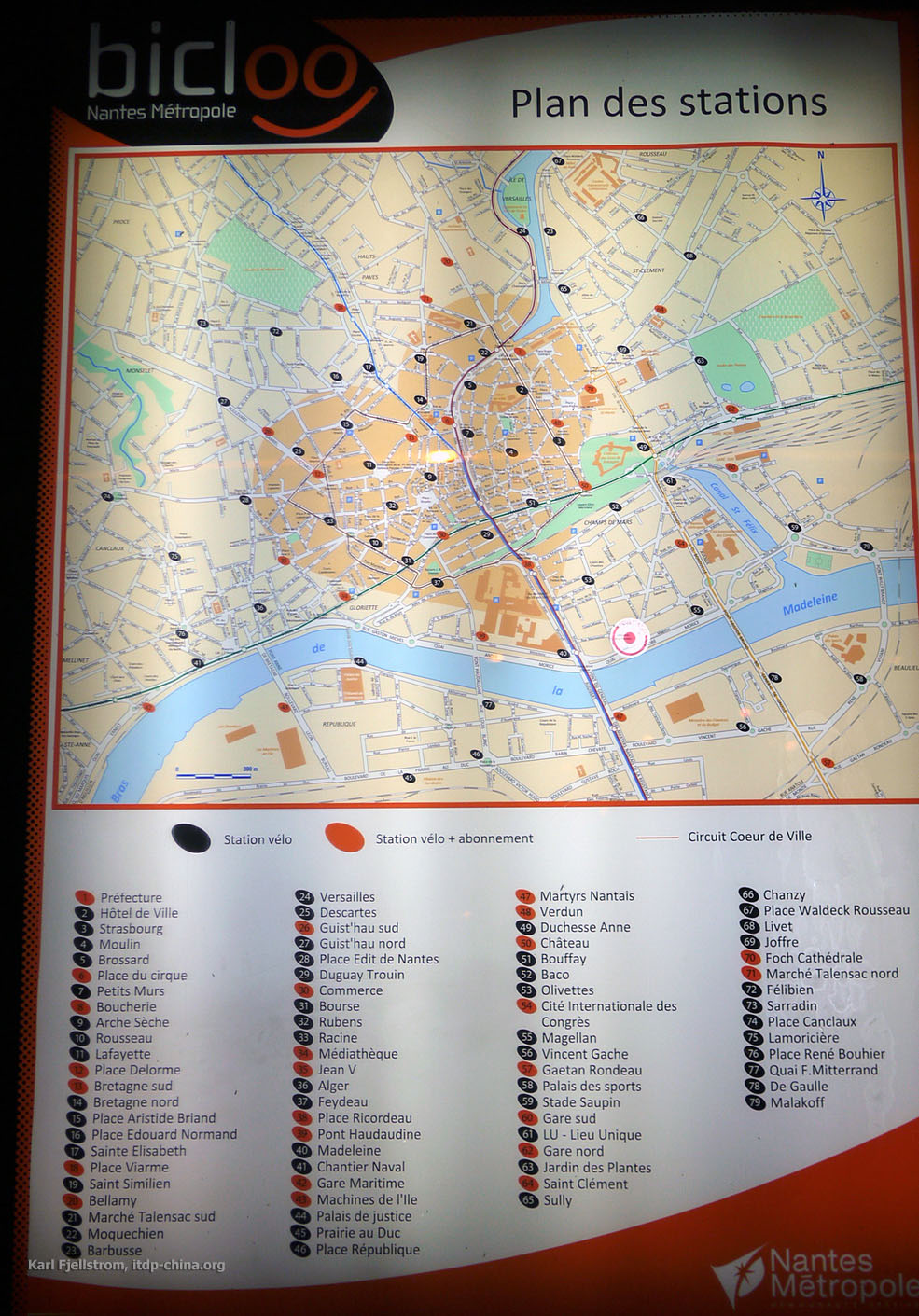

It is important to inform the riding public where bike parking and BRT access are. This information should be on maps, apps, and signs.

31.2.7.3Bicycle Parking Security

Since bicycles are typically parked for six to eight hours, or longer, every day, in the same place at BRT stations, concerns about theft and vandalism are particularly strong. The tenets of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) offer guidance for creating secure and comfortable parking facilities.

- Locate the parking in view of security or public transport staff;

- Locate the parking inside the paid area;

- Locate the parking in full view of the public (which has the additional effect of a marketing tool to encourage bicycle use; potential patrons will see the parking and decide to try it on their next trip);

- Provide clear exit paths from the parking area, with no hidden corners or obstructed areas;

- Ensure there is enough space so that customers can lock and unlock their bikes without tripping over other bikes;

- Install security cameras if other measures are insufficient to deter theft and vandalism;

- Provide sufficient lighting, perhaps motion sensitive;

- Charge a fee for the parking, which can be used to fund a dedicated security person.

Cyclists may be willing to pay a fee for greater security, or the public transport operator can provide security as part of the service. The latter is preferable, since additional fees become barriers and, given a choice, fewer people will use this option if there is an additional cost involved. Some prefer to travel their whole route by bicycle rather than pay a fare and parking costs.