13.2BRT Operating Contract Types

Simple, genuine goodness is the best capital to found the business of this life upon. It lasts when fame and money fail, and is the only riches we can take out of this world with us.Louisa May Alcott, novelist and poet, 1832–1888

The number of different types of vehicle operating contracts used in BRT systems continues to grow, but these types can generally be grouped into the typology of vehicle operating contracts listed in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1Contract Forms Typical of BRT Systems and Their Pros and Cons

| Contract Type | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profit sharing | Operator is paid a predetermined share of total system revenues, based on a pre-agreed-upon formula (usually linked to bus kilometers, customers served, or a combination). |

|

|

| Service contract (gross cost) | An operator is paid to operate a minimum number of kilometers of public transport services over the life of a contract anywhere directed by the municipality. Revenues are owned by the municipality, though may be collected by the operator. |

|

|

| Area contract (gross cost) | An operator is paid to operate a set of services within a zone, anywhere instructed by the municipality, usually by the bus kilometer or the bus hour. Fare revenue is owned by the municipality. |

|

|

| Area contract (net cost) | A private operator provides a set of services determined by the municipal authority within a specified zone, and owns all fare revenue in that zone. |

|

|

| Design-build-operate forms | Concessionaire is given a long-term contract to design, build, and operate a public transport system. Contractor owns fare revenue. |

|

|

| Route contract (gross cost) | Operator has a license with a city authority to provide bus services specified by the municipality on a route or a particular route, but revenue is owned by the municipal authority. |

|

|

| Route contract (net cost) | Operator has a license with a city authority to provide bus services specified by the municipality on a route or a particular route and all fare revenue is owned by the operator. |

|

|

| Unregulated entry with quality control | A private operator can get a license to operate anywhere, any time, so long as the vehicle is the right type, and it is properly maintained. |

|

|

| Unregulated entry without quality control | A private operator can get a license to operate anywhere, any time, with any quality of vehicle so long as the vehicle is the appropriate type. |

|

|

+ The term municipality in this context refers to whatever public authority is responsible for the administration of the municipal public transport system

Source: Modified from PPIAF Urban Bus Toolkit at: https://ppiaf.org/sites/ppiaf.org/files/documents/toolkits/UrbanBusToolkit/assets/3/3.4/34(i).html

While there is more than one way of grouping contract types, the typology in Table 13.1 groups them based on the following characteristics:

- Geographic share of the market: A contract may cover only one route (route contract), an area of the city (area contract), or have no specific geographic range (service contract);

- Ownership of the fare revenue: A contract may assign ownership of the fare revenue to the private operator (net cost) or to the public authority responsible for public transport in the city (gross cost). A city might allow a private operator to collect the fare revenue on behalf of the public authority, but if the revenue belongs to the public authority it is still considered in this typology a “gross cost” contract;

- Payment method: Any form of payment of the vehicle operator based on an operating characteristic, such as payment per bus kilometer, or per passenger kilometer, or per bus hour, or any operating characteristic other than the direct receipt of fare revenues, is considered in this typology as a “gross cost” contract;

- Degree of financial ring-fencing: A new category, “profit sharing,” was created to describe those contracts where a BRT system is financially ring-fenced, and all system profits are shared by a formula. Net cost contracts are also generally financially ring-fenced, whether subsidized or not, while gross cost contracts are not financially ring-fenced;

- Degree of infrastructure construction and maintenance in the contract: Any contract that includes some element of infrastructure construction and maintenance together with an operating contract has been grouped together as a “build-operate-transfer form” of contract. Even if the payment to the operator is based on an operational characteristic, if infrastructure is involved the terms of the contract tend to be much longer, and the nature of the contract quite different, so they have been classified separately.

The distinction between whether there is competition “within” a defined public transport market or competition “for” a particular public transport market is taken up separately in two later sections. The sections deal specifically with whether or not there are multiple operators serving the same BRT system, and whether or not the contracts were competitively tendered or negotiated. The presence or absence of quality of service contracting is also treated separately, as its inclusion created too complicated a matrix of types.

Most of the contractual forms being used in BRT systems were first developed for normal bus services, or for metro systems, with the exception of the “profit sharing” type of contracts, which are an innovation that was introduced by the TransMilenio BRT system and subsequently replicated in some other BRT systems.

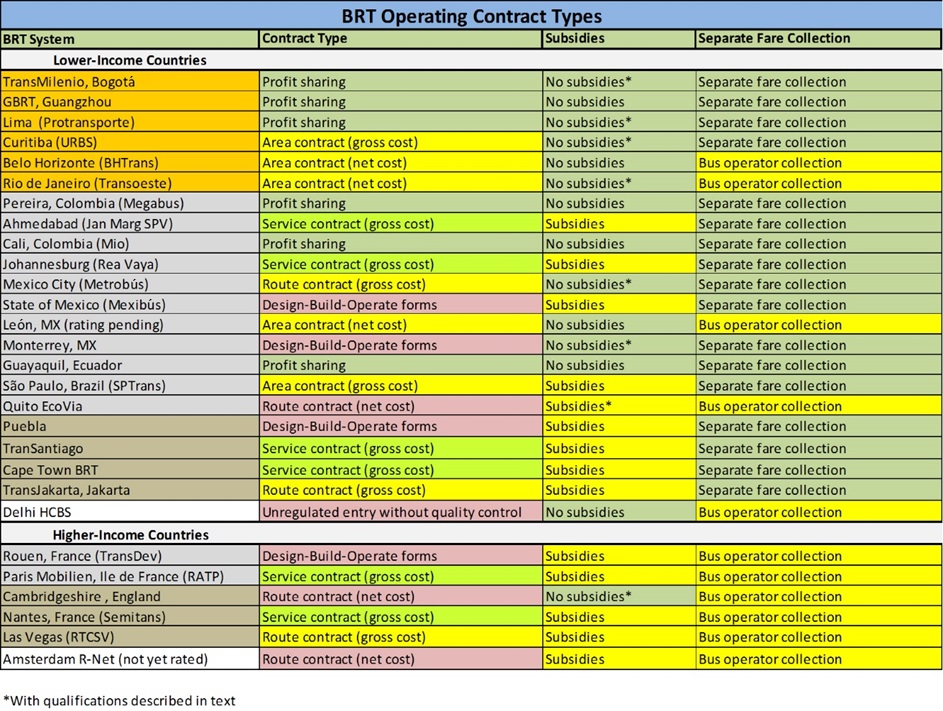

Figure 13.3 lists many of the better BRT systems by the type of contracts that govern their vehicle operation. It also lists those systems that are subsidized or not, and those systems for which fare collection is separated from the vehicle operator. In Figure 13.3, there is a correlation between the better quality systems and those that do not require subsidies. Systems not requiring subsidies are coded green and systems requiring some subsidies are coded yellow. Generally BRT systems are built on the corridors with high levels of demand where preexisting bus services tend to be more profitable. This is likely to be where user benefits are also maximized. It also appears to be true that the systems that are designed for full cost recovery also tend to be the better designed systems overall.

There also tends to be a correlation between the better BRT systems and those with separate companies managing the fare collection system. Separating fare collection from the vehicle operators tends to give the municipality more control over the private operators. Systems with separated fare collection are coded green and those where fare collection is managed by the vehicle operators themselves are coded yellow.

As can be observed from Figure 13.3, there is a clear relationship between “net cost” contracts in lower-income economies and direct collection of fare revenue by the vehicle operator. In lower-income economies, gross cost contracts always involve a separate fare collector, whether it be the government or a separate private contractor.

In higher-income economies, by contrast, gross-cost contracts are the norm, and fare revenue is generally collected by the operator, though the fare revenue is owned by the public authority in charge of the system and not the vehicle operator. This contract structure can work when fare collection systems are largely electronic, and it can work where the public authority or its third party auditors can effectively monitor the integrity of the fare collection system. In lower-income economies, where familiarity with electronic fare systems and the sophistication of public authorities is generally lower, this sort of contract form has yet to emerge.

There is a growing consensus among most experts that certain contractual forms work better than others, providing a safer and higher quality of service at the most reasonable price to consumers and taxpayers. The best contracts distribute risks and profits fairly between the public sector and the private sector, minimize the risks to the public sector of open-ended financial commitments, create incentives to operate efficiently but continue to provide a high quality of service. In Figure 13.3, the contractual forms that perform the best are coded green, those that perform the worst are coded pink, and those that have problems that can generally be addressed within the same contract structure are coded yellow. It should be noted, however, that any contract can be written well or poorly, and that most of the problems of each type of contract can be overcome by a good contract, and most of the best forms of contracts can be undermined by a poorly written contract.

13.2.1BRT Operating Contract Types in Lower-Income Economies

In lower-income economies, where BRT systems have been financially self-sufficient and ring-fenced, it has been possible to set up contractual relationships between private BRT operators and public authorities in such a way that the system profits are shared by the public interest and the private system actors. If done correctly, this contractual form creates incentives for cost savings, minimized subsidies, safe operations, and high quality of services. This new contractual form, defined here as “profit sharing,” is a contractual innovation that emerged out of the Bogotá TransMilenio BRT system, on the advice of McKinsey. It will be explained in detail below. It has since been copied in most of the Colombian BRT systems, in Guayaquil, in Lima, and in Guangzhou, China. As these systems have tended to have better services (though they are far from perfect), this contractual form has been coded green. There are also some very good BRT systems in lower-income economies that operate with a service contract (gross cost) that is not linked to any specific corridor or zone. These contracts, if properly supervised, can function well inside BRT systems, and cause relatively few problems, and as such have been coded light green. Ahmedabad, Johannesburg, Cape Town, and the latest contractual forms in Santiago, Chile use this form of contract.

There are, however, gold- and silver-rated BRT systems in lower-income economies (primarily Brazilian systems) operating with area contracts (gross cost), such as Curitiba’s BRT system and São Paulo’s Expresso Tiradentes, which have had problems, but they are problems that can be overcome. These are coded yellow. There are also some very good area contracts (net cost) such as Rio’s TransCarioca and TransOeste, and Belo Horizonte’s Cristiano Machado and Antonio Carlos BRT corridors, that have known operational problems but that are correctible within the same general contractual framework. They have also been coded yellow. There are a few Build-Operate-Transfer contracts in lower-income economies, primarily in Mexico (Puebla, Monterrey, State of Mexico), where the fare revenue is owned by the private builder of the infrastructure. In these examples, this form was generally built on faulty financial assumptions and is unstable. As such, it has been coded pink. There is also one route contract (net cost), the Ecovía line in Quito, which had significant contractual problems and as such was coded pink. There is also one example of a BRT with unregulated entry without quality control, the Delhi HCBS system, which has had significant operational problems, and as such this contractual form is coded pink.

13.2.1.1Profit-Sharing Contracts

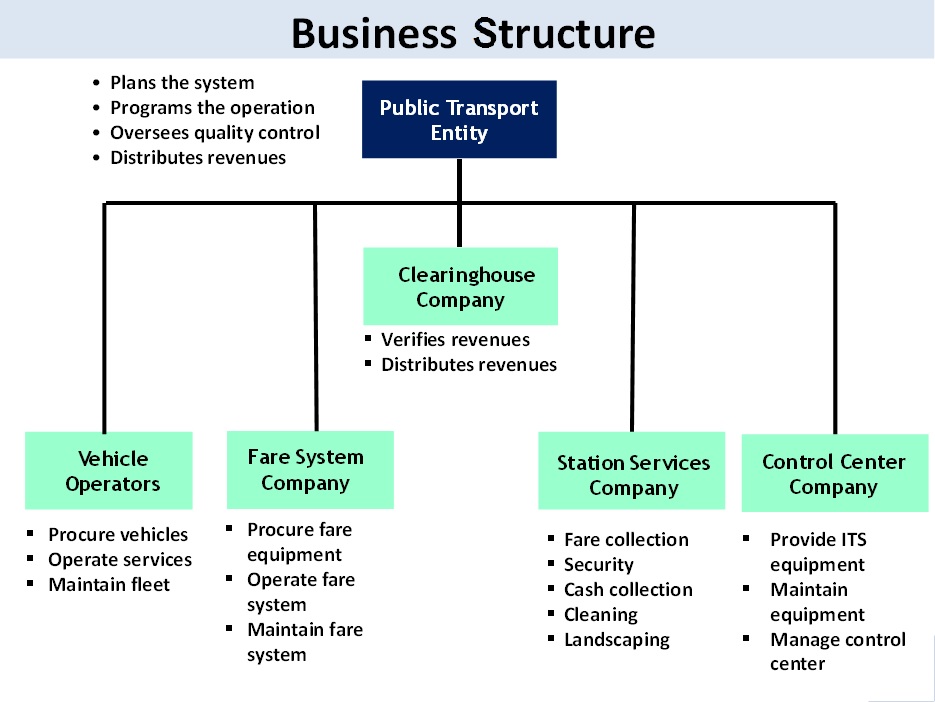

Many of the gold-, silver-, and bronze-rated BRT systems in lower-income economies in our survey use a contractual form identified here as “profit sharing.” In almost all of these contracts, the vehicle operators are paid based on an operating characteristic, such as the number of bus kilometers, the number of customers served, or some combination of system characteristics. In this way, a profit sharing contract is similar to a service contract (gross cost). The important difference, however, is that ultimately the total payment to the vehicle operators is a fixed percentage of the system’s total operating revenue. The more revenue the system makes overall, the more the operators are paid. In this important sense, it is a profit sharing contract, and not a gross cost contract. How this works is best made clear by an explanation of the TransMilenio profit sharing contracts work, as most of the other profit sharing contracts were based on TransMilenio.

In the case of the contracts within TransMilenio, there is a public BRT authority, TransMilenio SA, which is a BRT system specific public authority. It contracts out vehicle operations to vehicle operating companies. These vehicle operating companies are paid on the basis of a combination of operating characteristics, mainly per bus kilometer and per customer. The amount that the vehicle operators are paid per kilometer is agreed upon in the contract for the life of the contract, and it is only increased based on certain external price indexes; increases in the fee per kilometer are in this way not related to the operator’s actual costs, but to general costs in society. The operator’s contract therefore allows them to make a big profit if they can lower their operating costs. This has been achieved primarily through the optimization of maintenance regimes, returns to scale in the procurement of spare parts, and the optimal deployment of labor.

Importantly, the vehicle operators never touch the fare revenue. The independent concession for fare collection helps ensure the system’s revenues are properly controlled and administered. If anyone with a vested interest were to be handling the revenues, then there will always be suspicion among the different stakeholders. An independent fare collection process means that none of the vehicle operators have any relationship to handling the fares. Further, through the use of real-time sharing of fare information, all parties have an open and transparent view of revenues. In TransMilenio, fare data is streamed simultaneously to all relevant parties, creating an environment of confidence in the system.

This company deposits all the fare revenue into a trust fund managed by a bank, also under contract to TransMilenio. The bank certifies that the amounts deposited by the fare collector are the same as the amounts collected at the point of sale terminals. It also distributes the payment to the vehicle operators and their creditors, as well as to the fare collectors, without the funds ever passing directly into a government bank account. In this way, the multiple vehicle operators are not worried that one operator is stealing from them, nor do they need to worry that the government is stealing from them. All of the revenue in this way is financially ring-fenced so that all money earned is paid back to the joint profit sharing companies of TransMilenio. If the fare revenue is enough to cover the operating costs of the BRT authority, they are also paid a share of the profits. And if the money is enough to cover the operational control center, or station security, all the firms engaged in these functions can become part of the profit sharing scheme.

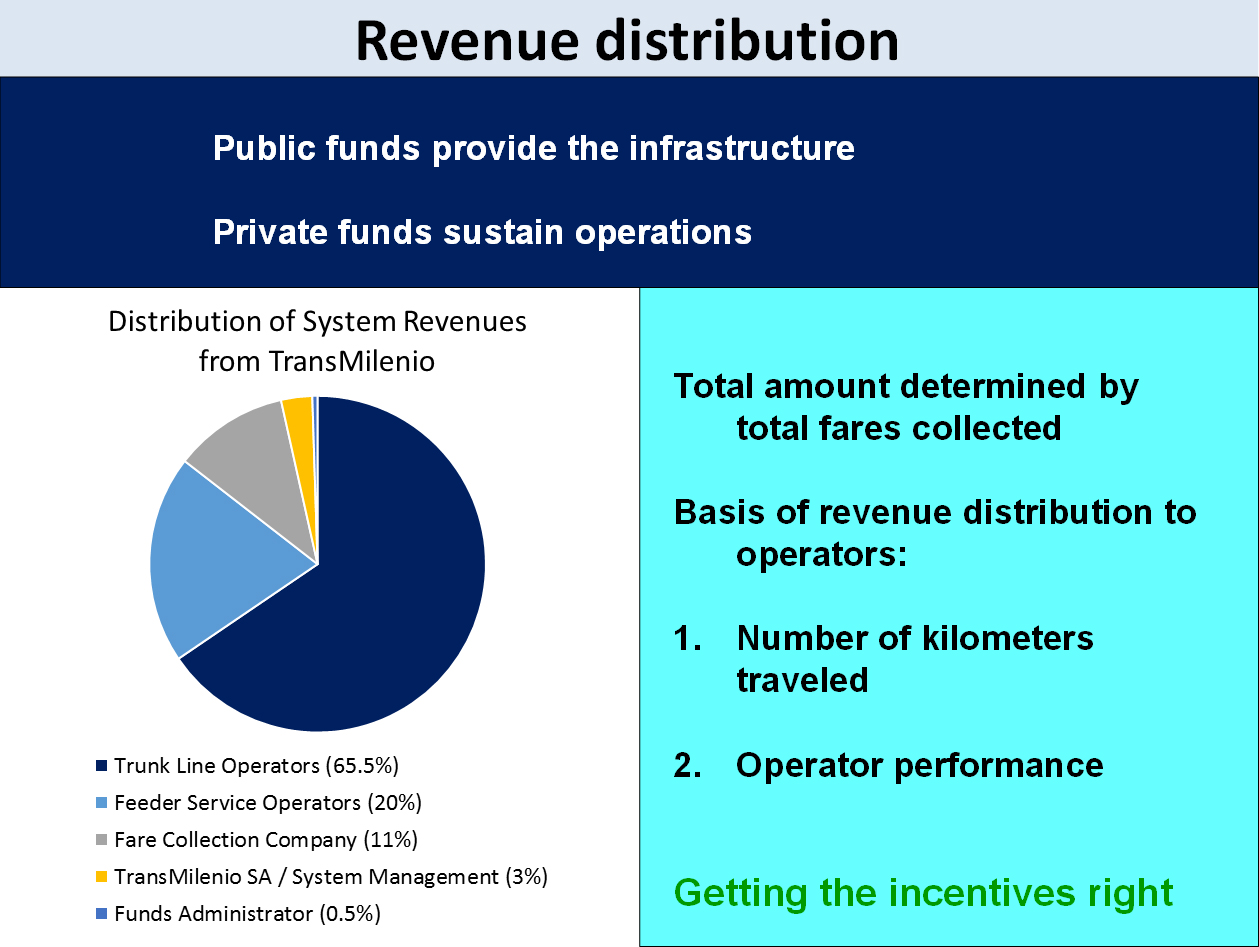

In the case of TransMilenio, the vehicle operators were responsible for procuring their vehicles and operating them. The fare collection system operator was responsible for buying the fare collection equipment and operating it. These costs were all seized by the operators in the monthly fee per bus kilometer (in the case of the vehicle operator) and by the flat percentage of the total revenue (as was the case of the fare collector). The specific profit sharing ratios for TransMilenio are shown in Figure 13.5.

To the customer, the services all look the same. The tight product delivery specifications ensure that the look and feel of each vehicle is quite similar, regardless of which operating company is managing the vehicle. Even though there are several operators, none have an incentive to operate in an overly competitive manner on the street. Each operator is making its revenues from the services that he or she operates and his or her share of the collective profits of the system.

TransMilenio SA controls the scheduling of trips and the routes of the operators. In theory, TransMilenio can assign any operating company to operate any route, but in practice it tends to program most route kilometers to the company with the closest depot. This allows flexibility for TransMilenio to move services from a corridor that is less than anticipated to one where it is anticipated.

The reason the contracts are not simple gross cost service contracts is that TransMilenio SA is contractually bound to increase the number of bus kilometers it assigns to the vehicle operating companies if the ridership increases beyond a certain level. Similarly, if ridership falls below a certain level, TransMilenio can cut services. In this way, unlike in a typical service contract (gross cost), the operators are partially exposed to demand risk. TransMilenio SA is contractually obligated to distribute all of the fare revenue based on the formula.

This contractual form has been extended to other less profitable systems by having the government pay one or more elements of the system’s costs. For instance, if the total system is not as profitable as TransMilenio, the government can cover the cost of the staffing for the BRT authority and still retain the basic integrity of the profit sharing contractual structure. If it is still not profitable, the government can subsidize the cost of all or part of the vehicle procurement and still retain a profit sharing contract structure.

In this model, the infrastructure was paid for by the government and handled separately. A separate public works agency issues the tender documents to competitive bidding for the infrastructure components (busways, stations, terminals, depots, etc.). The construction work is conducted entirely by the private sector but paid for out of general tax revenues.

TransMilenio operated without subsidies for more than a decade. While a populist mayor eventually decided to freeze the fares, creating the need for subsidies, the financial soundness of TransMilenio was protected by a contractual obligation. This was an obligation on the part of the city to compensate any losses that result from the failure of the city to approve fare increases necessitated by increases in publicly published input costs, such as the price of fuel and the consumer price index.

The profit sharing agreements of TransMilenio have been criticized in a number of ways. The fare collector, receiving 11 percent of the profits, is receiving far more than could generally be justified by the cost of the equipment and the service provided. TransMilenio did not increase the services sufficiently to avoid overcrowding on the system in order to cut costs and increase the profits of the operator. The operational control system, a government position directly under TransMilenio, ended up hiring a lot more staff than necessary, and probably should have been contracted out as well. But in general, the contractual structures devised for TransMilenio overcame a lot of the problems with previous contract structures.

For this reason, similar profit sharing contracts were developed in BRT systems in Lima, Peru; Guangzhou, China; Guayaquil, Ecuador; and in most of the Colombian systems. In Lima, there were problems that the contracts were written on the assumption that another 10 kilometers of trunk infrastructure would be built to support the operations, but they were never built, throwing the contracts into confusion. In Guayaquil, municipal officials have had to deal with a nationally mandated US$0.25 fare. Nonetheless, though still in need of refinement, most experts consider profit sharing to be a best practice.

Decision makers wanting to use a profit sharing contract structure should decide from the beginning to design the BRT system to be financially self-sustaining. This decision should drive the technical design process, rather than the other way around. The administrative and organizational structure of the system will have profound implications for the system’s efficiency, the quality of service, and the system’s cost over the long term.

13.2.1.2Service Contracts (Gross Cost)

In a number of lower-income cities, most of the contractual forms developed in TransMilenio were copied but without being able to achieve the same financially ring-fenced cost sharing. Ahmedabad’s JanMarg, Cape Town’s MyCiti BRT, Johannesburg’s Rea Vaya, and Santiago’s TranSantiago are all operated by vehicle operators under a general service contract that pays them based on service parameters (mostly by the bus kilometer), though in the case of TranSantiago the formula is based on many service parameters (Gómez-Lobo, 2013). These systems, however, did not specifically link the payments to the operators to the profitability of the system.

This contract structure avoids a lot of the typical problems with vehicle operating contracts in BRT systems. First, because the contracts are to operate a fixed minimum number of bus kilometers over the life of the contract, and because these can be operated anywhere within the system at any time, the public authority responsible for managing the system can easily reallocate services from one part of the system to another without needing to renegotiate the contracts. Since payment is largely based on bus kilometers, there is no destructive competition for customers at the curb, no waiting until vehicles are full, no shortage of service in off-peak periods or less popular routes. There are no problems of providing services between zones. There are no problems with multiple operators using the same infrastructures, so the operator with a service contract is less entrenched than in an area- or route-based contract. As the operators are paid a fixed amount per kilometer, set for the life of the contract, the government knows in advance what its costs will be, and the operator has an incentive to operate more efficiently to increase profits. As such, this contract structure is fully compatible with BRT operations.

Nonetheless, this sort of contract does not provide a strong incentive for the vehicle operator to ensure that the fares are collected, attract more customers to the system, or optimize their services. This is because they get paid more the more kilometers they operate, and they do not really care if the system overall is profitable. In all three cases where this contract structure was implemented in higher-income economies, there are continuing problems with fare evasion, as well as with ongoing and escalating operating subsidies.

13.2.1.3Area Contracts (Gross Cost)

Curitiba and São Paulo, two of the cities where some of the most important innovations in BRT system development occurred, both operate their BRT systems under area-based contracts (gross cost). In these contracts, private vehicle operators have control over a large part of the city, including both BRT and non-BRT routes, but the fares are collected by a third party, in both cases the transit authority of the city. This form emerged after decades of efforts on behalf of the municipality to gain more quality control over the vehicle operators.

When BRT was introduced into Curitiba and São Paulo, most of the city’s bus services had already been granted to large bus companies. These contracts were based on the “selective area principle.” They gave all bus routes in a zone of the city to a single bus franchise. This contractual form had been in place since at least the 1960s. Initially, these were area-based contracts (net cost) where the operators collected the fare revenue and kept it. In both cities, these private bus companies were formal companies, but not with the same degree of transparency as would be required in the first world. The financial performance of these firms was never clear, in part to avoid paying corporate taxes.

Before the BRT was implemented, these same private bus companies had area based (net cost) contracts. They charged their own fares, set their own rates, and collected the fares directly. One of the main problems with area contracts (net cost) is that it is hard to introduce routes that pass from one zone to another, and it is hard to introduce a free transfer from one route to another. More than one operator would use certain BRT stations, particularly on corridors between zones and in the downtown and there was no clear way to distribute fare revenue between the operators.

In 1980, during his second term, Curitiba mayor Jaime Lerner wanted to introduce a single unified “social” fare and eliminate the paid transfers. With bus companies collecting their own fare, however, if a free transfer was implemented, the bus company carrying the customer for the second part of the trip would not get paid. To some extent this problem is mitigated by the fact that most journeys in the evening would pay the company that provided the free trip in the morning trip. Nonetheless, there were winners and losers. The problem was ultimately resolved by the creation of a “compensation fund” that was managed by a new public authority, URBS (Urbanizacao de Curitiba). Initially companies making extra profits paid into a compensation fund managed by URBS, who then paid the loss making companies. This proposal worked out well, and the separate companies began to trust the government handling this process.

In a later round of reforms, when Curitiba decided to introduce more interzone routes, after some struggle, the private vehicle operators agreed to shift to an area-based contract (gross cost) where URBS took over direct collection of all of the fare revenue and paid each operator by the bus kilometer. This emerged over time, after trust with the private operators had been established (Ardilo-Gomez, pp. 140-147, 2004).

In Curitiba the fares were allowed to rise high enough that the bus services managed under URBS, including the BRT routes and inter-corridor routes, remained as a whole profitable. Curitiba ended up with public transport fares considerably higher than in other parts of Brazil, but to date has avoided the need for public subsidies.

São Paulo has a lot of corridors that would qualify as BRT were taxis not allowed to operate in the bus lanes. It has one elevated silver-rated BRT, Expresso Tiradentes, which is a full-featured grade-separated BRT with off-board fare collection. The area-based contracts have led to weak inter-area public transport services, including through the central business district. The nature of these contracts changed over time from gross cost to net cost. After most of the bus services in São Paulo were privatized in the early 1990s, the new private operators that sprung up were under area contracts (gross cost), and vehicle operators were paid on a fee per kilometer basis. Fares were collected directly by the public authority SPTrans. This had the advantage of encouraging operators to drive more safely as they were not competing for customers. However, it gave too much latitude to private bus companies to set their own routes, which inevitably were longer than they could commercially justify. Subsidies began to escalate, and by the late 1980s one-third of public transport operations costs were subsidized by the Municipality of São Paulo. Thus, gross cost contracts in São Paulo came to be associated with government deficits and weak regulation. Facing unsustainable deficits, São Paulo shifted in 1991 to area contracts (net cost), paid by the customer. However, fare collection remained with SPTrans, mainly as a control so the city knew how much money the system was making. This shifted the demand risk back onto the vehicle operator. This helped to control subsidies for a time, but vehicle operators began cutting services to lower demand areas and during off-peak periods. Profits suffered. Competition from minibuses worsened, and the average age of the vehicle fleet began creeping up from three to seven years, and service quality began to decline. Hence, this net cost contract was associated with declining service quality (Golub and Hook, 2003, p. 14).

When the new “Passa Rapido” bus corridors were introduced in the Martya Suplicy administration (they did not qualify as BRT once they allowed taxis to use the lane), the interligado integrated fare system was introduced, which allowed for free transfers between routes. By the time that the Expresso Tiradentes BRT opened during the Serra administration, the contracts had already returned to an area-based (gross cost) contract based on kilometers operated. The integrated fare system significantly increased public transport mode share in São Paulo but at a significant cost to the municipality in additional subsidies to the system.

13.2.1.4Area Contract (Net Cost)

Two of the best new BRT systems in Latin America, the new Gold Standard BRT systems in Rio de Janeiro and Belo Horizonte, are operated by area licenses on a net-cost basis. In these two cities, as in other Brazilian cities, the zones of the city were divided into separate area licenses for different vehicle operators. In these two cities, however, the vehicle operators never turned control of the fare revenue over to a public authority. As such, they continued to collect and keep the fare revenue.

When the BRT systems were opened in the two cities, they passed through the historical territory of more than one vehicle operating company with area licenses (net costs). The vehicle operators maintained control of their operating territories by forming a consortium of the companies in the affected areas. They turned off-board fare collection over to a third party—the same company that already managed fare collection for their conventional vehicle operations in each city. This third party company then splits the fare among the BRT consortium partners based primarily on boarding customers. It is noteworthy that this fare collection company was created by the same historical vehicle operators. That is, in the final analysis, the fare is collected by the vehicle operators themselves.

This operating arrangement has similar benefits to the profit sharing arrangements of TransMilenio, but it is entirely in private hands. It fully privatized not only the vehicle operations but also fare collection, while insulating the city from any risk of paying operating subsidies.

There is an important difference between the structure in Belo Horizonte and Rio. In Rio, the contracts with the operators are signed directly with the Municipal Secretary of Transportation. In the case of Belo Horizonte, the operating contracts are signed with a transport authority, BHTrans. In the view of most experts, services in Belo Horizonte are better managed due to the superior oversight made possible by the existence of BHTrans. The system in Belo Horizonte has not been subjected to the same level of criticism as the services in Rio. By losing control over the fare revenue and having weak regulatory authority over the vehicle operating contracts, the municipality has ceded considerable control over the quality of operations. In TransOeste, for instance, service frequency was well below what was needed and the operators profited handsomely from crowding customers onto each bus. Performance was bad enough to reduce Rio’s TransOeste service from a Gold Standard BRT to a Silver Standard BRT. The city authorities had limited contractual rights to force the operators to buy more vehicles and expand the services.

As the BRT systems are expanding, further industry consolidation is being prepared, and Rio vehicle operators are organizing to create a citywide BRT operating consortium. The division of payments between companies with control over different areas will become an issue to be settled internally by the board of a private consortium. It has yet to be implemented as of 2015 but merits monitoring.

In León, Mexico, the Optibús system is operated under a similar contractual structure. In León, the consortium operates both the trunk corridors and the feeder services. However, the distribution of revenues is handled differently for each route type. Fares are not independently collected but rather handled directly by the consortium. Even though the system has an integrated fare system and a single fare, fares collected by the feeder buses are kept by the feeder vehicle operators. The income of the feeder operators is thus based on the number of customers. The fares collected on the trunk corridors are deposited into a fund established by the consortium. Funds are reportedly distributed to trunk operators on the basis of number of kilometers travelled. However, since the payment system is not transparent, the exact nature of the revenue distribution scheme is unclear to the municipality and the public. For a while, since the feeder operators only keep the fares that they collect, they only have an incentive to serve customers during the morning commute. On the return trip in the afternoon, the trunk line operators collect the revenue. Not surprisingly, then, the feeder companies provided very little service, and thus make the trip home a relatively unpleasant and difficult experience for the customer. The city ultimately fixed the problem by creating a compensating fund.

Ultimately, some of the problems with area contracts (net cost), such as lack of compatibility with inter-area routes and off-board fare collection, can be resolved. It is likely that other problems, such as generally weak performance, could also be resolved by improvements in the contract. Ultimately, however, the public loss of control of the fare revenue significantly limits the day-to-day ability of the municipality to demand improvements in the quality of service if there are shortcomings.

13.2.1.5Route Contract (Gross Cost)

Many BRT systems in lower-income economies continued the practice of route licenses even after a BRT was implemented. With TransJakarta in Jakarta and Metrobús in Mexico City, the BRT system only had trunk services, and services on new BRT trunk routes were turned over to the same companies or collectives that dominated the licenses on the same route. While the nature of the contract changed, and in both cities the operators were paid a flat fee per kilometer of service (gross cost), in both cases their operation was limited to one trunk corridor. As the networks expanded, and severe congestion formed at the transfer points between the two corridors, this route contract (net cost) contractual form made it difficult for the BRT authority to introduce inter-corridor routes. In both cases, however, this problem was overcome by negotiated profit sharing agreements between the two operating companies affected. Nonetheless, to avoid this problem, most BRT systems do not award route contracts (gross cost), but instead offer a fee per kilometer that can be operated anywhere in the BRT system’s service area.

13.2.1.6Route Contracts (Net Cost)

Most BRT systems in lower-income economies grew out of regulatory regimes where public transport services were dominated by route contracts (net cost). With this type of contract, many small to large individual operators have a license, usually from a municipal department of transportation, to operate a public transport service on a particular route or a set of routes and to collect all of the fare revenue on those routes. This ends competition on the street within a particular route, but if there are routes that overlap, there is still competition on the street for customers. When applied to a BRT system, as it was in the Ecovía system in Quito, it led to very weak municipal control over the operator and an inability to integrate services between BRT corridors. In Quito, the municipality initially bought the BRT vehicles, and then tried to get the operators to pay for them in installments. Because the private operators that controlled the BRT routes also collected the fare revenue, however, the municipality never knew for sure how much money the system was making. Matters were made more complicated by national regulations fixing the fare at around US$0.25 per trip, very low by regional standards. It also proved very difficult to integrate services between the Ecovía routes and the Trolebus routes and other BRT routes, forcing all customers to pay twice.

13.2.1.7Design-Build-Operate-Transfer Contracts

While popular for use in metro projects and toll roads, design-build-operate-transfer contracts are relatively little used for BRT projects in lower-income economies. In a typical metro build-operate-transfer contract, a private consortium would offer to design, build, and operate a metro system or toll road, and then it would be allowed to collect all of the fare or toll revenue for a long period of time, usually twenty or thirty years. After this, the infrastructure would nominally transfer back to the government. The government would ideally hold a competitive tender and offer the job to the firm that promised to build and operate the system for the lowest price. In the case of toll roads, this financing form sometimes works, as toll revenues are sometimes sufficient to cover the cost of building and maintaining the road. In the case of metro projects, the government would generally end up paying for all of the infrastructure and subsidizing the operations. Also, it would pay a premium for financing the system, but it would only have to pay for the system in annual installments, and it would get the infrastructure built with the least management responsibility placed on the government. This form has frequently been used to get around debt ceilings. The construction companies would usually front the money and earn it back at a premium over time in annual payments from the government. Sometimes these projects would tell the public that all the costs would be covered by the fare revenue. However, the private companies would generally require a demand guarantee on the part of the government and freedom to increase the fares or tolls. Demand levels would inevitably fall short or the government would refuse to raise tolls or fares sufficiently to cover the losses. Until recently, this contractual form was not used for BRT projects in lower-income economies.

However, there are now several BRT systems in Mexico where BRT operations are under a variation of this form of contract. The federal government there created a national government fund, called Public Transportation Federal Support Program (PROTRAM), to finance urban public transport from nationally collected revenues from national toll roads. This stimulated a lot of BRT system developments, particularly in the poorer cities and states outside of Mexico City. PROTRAM required a 35 percent private sector investment in the project in order to be eligible for the funds. As a result, several Mexican cities moved forward with BRT systems where the infrastructure was built by private companies that were also paid out of the fare revenue.

In Monterrey, there is no BRT authority. There are three contracts, one with a private vehicle operators’ consortium. The vehicle operators are paid on a gross-cost basis (per kilometer) that is not part of a profit sharing arrangement. A separate private company that constructed the stations and terminals receives a portion of the fare revenue in the form of 1.1 pesos per person using the stations and terminals. The system is not financially ring-fenced. A third concessionaire, directly contracted by the state government, collects the fare revenue. It only recently began operation, so it is too soon to determine how much the system will need in subsidies.

In Puebla, the fare collection system is controlled by the company that built the infrastructure. It takes part of its costs out of the fare revenue, and then deposits the balance into a trust fund from which the vehicle operators are paid on a gross cost basis. This financial setup proved unsustainable, so the government had to step in and take control of the fare collection from the infrastructure provider. The system is subsidized.

In the State of México, there was a similar arrangement. A small public authority under the state government, Sistema de Transporte Masivo y Teleferico del Estado de México (SITRAMYTEM), contracted out infrastructure on three different lines to different construction companies, which in turn collected the fare revenue, paid themselves, and then paid the balance into a trust fund. Each had its own fare collection format, so the system was not integrated and users wishing to use multiple lines needed three different fare cards. The fleet operators were paid on a gross cost basis by the bus kilometer, out of the trust fund that is controlled by SIRAMYTEM. On Line 1, the system did not recover its costs, and the State of México had to take over the fare collection and infrastructure contract. Line 2 just began operations, but is likely to face similar problems. Demand on the corridor was lower than projected in part because the government failed to regulate competing traditional unregulated route concessions parallel to the new BRT service, which only operates with a time and cost advantage during peak hours.

As such, the track record with DBO form contracts in lower-income economies is decidedly poor. It is likely that the financial projections were invalid from inception just to ensure that the projects complied with national government PROTRAM funding requirements. It may be that these types of contracts could be improved, but only if federal guidelines are made more realistic and the systems are not designed with false assumptions about their potential profitability.

13.2.1.8BRT Systems with Unregulated Entry

“Unregulated entry without quality control” and “unregulated entry with quality control” are not generally seen in BRT systems, and they are almost universally accepted as being inappropriate for BRT systems. Under these two contract types, informal operators are allowed to operate as many vehicles as they would like on as many routes as they want whenever they want, so long as they have a vehicle of the appropriate type, with or without some control as to the quality of the vehicle. These systems tend to lead to informal, often criminal forms of regulation and control of the industry, an oversupply of vehicles on trunk routes during peak periods and an undersupply on lower demand routes and during nonpeak periods. These systems tend to have high pedestrian fatalities at curbside, as vehicles compete for customers. They tend to have problems of not following any schedule, not stopping at predetermined stops, and the vehicles tend to be old, uncomfortable, and unsafe.

In the first generation of busways, starting in the 1980s, there were many busways with these contractual forms in lower-income economies, but they generally failed to reach BRT status. They had several serious problems. First and foremost, if too many vehicles are operating inside them, BRT systems saturate, and busway speeds can drop to below mixed traffic speeds. TransMilenio, in fact, was an “open” busway with unregulated entry prior to the creation of TransMilenio, and its operating speeds averaged only around 12 kilometers per hour, little more than standard mixed traffic operation due to busway saturation.

In Delhi, one of the main problems with the High Capacity Bus System (HCBS), which was rated Basic BRT, was that there were very weak barriers to entry for individual owner-operated vehicles registered with the STA to use the BRT system. These vehicles were frequently old, polluting, and subject to failures (see Figure 13.6). As a result of vehicles operating under this outmoded contractual form being allowed to use the BRT infrastructure, these vehicles frequently broke down, congesting the busway. Further, their numbers were greater than the busway could accommodate, leading to vehicle queueing at the stations and intersections that lowered operating speeds. All of this tarnished the image of the HCBS and contributed to its decidedly mixed political reception.

13.2.2BRT Operating Contract Types in Higher-Income Economies

In higher-income economies, the relative transparency of business operations, more effective governmental regulatory powers, and greater experience with sophisticated contracts and their enforcement have less trouble with some contractual forms that have caused significant difficulties in lower-income economies. That being said, the types of contracts most typical in higher-income economies all tend to leave government exposed to open-ended subsidies with relatively limited incentives for greater service efficiency. BRT systems are also smaller in higher-income economies, so the contract structures have rarely been developed specifically for a new BRT system, and operations are generally contracted out to the same vehicle operating contractors, using the same contractual forms that operate normal bus services in the municipality.

It has not yet proved possible to create a BRT system in higher-income economies that is financially self-sufficient and financially ring-fenced to the point where a profit sharing contract has been tried. It is, however, theoretically possible to build a BRT on the highest demand public transport corridors and structure the business in such a way as to achieve full financial recovery to the point where profit sharing could be discussed.

Currently, in higher-income economies, a citywide public transport service contract (gross cost) that encompasses the BRT routes is the most common contractual form in BRT systems (Paris and Nantes in France). There is also one system (Las Vegas, U.S.) where operators are given route contracts (gross cost). These consist of one build-operate-transfer form of contract in which the builder of some rail infrastructure has a long-term operating concession that also covers the BRT system (Rouen, France), and two route contracts (net cost) in which an operator has a contract to provide services on specific routes and collects all the fare revenue for those routes (Cambridgeshire, UK; Amsterdam, Netherlands). The relative merits and problems of these contractual forms in higher-income economies are similar to those in lower-income economies but generally on a much smaller scale.

The context for contracting out public transport operations in higher-income economies is quite different from in lower-income economies. Both net cost and gross cost contracts have the problem that, unless otherwise mitigated, they create no incentive for transit operators to reduce their costs. However, in higher-income economies, the government body that regulates these contracts usually has at least some chance of knowing what the firm’s costs are. Operating companies that generally have reasonably transparent corporate governance have to be audited and publish financial statements.

The deregulation of public transport services in England under the Thatcher administration, and later the encouragement within the European Union of private contracting of private operators, has over time led to the emergence of private firms able to provide these services. It is mostly these same firms that are offering their services in the United States. Initially, it was quite difficult for private firms to compete with long-established municipal transit operating companies that had trained staff, land, depots, and established supply relationships. As such, privatization began mostly on new routes, new services (such as public transport for disabled people), in newly urbanizing areas, and in smaller towns where government did not have the staff or experience to manage a public transport system. Many of the contracts are essentially management contracts, where firms are given permission to manage and operate public sector assets (depots, vehicles, etc.) on behalf of the government. Usually this involves renegotiating labor contracts, though in most cases these firms have managed to make the transition to private contracting without fundamentally disrupting labor relations (as per interviews with Veolia US).

Nevertheless, the number of firms that are likely to bid on an operating contract remains small. Entering into the market that was previously dominated only by a public sector transit operator meant that there were not existing local private vehicle operators to contend with, only public sector labor unions and their political clout. Only a very limited number of firms have emerged to enter this commercial space and are capable of bidding on municipal vehicle operating contracts, and these firms have gone through frequent changes in ownership structure.

Today, some of the largest private firms are TransDev, a French company that used to be Veolia, and before that was Connex; Stagecoach (Scottish/British), Tower Transit (Australian), and Keolis (French-Canadian), which is owned by the French national railways (SNCF) and a group of Canadian investors. These same firms have tended to buy up smaller private vehicle operations, and their names appear in virtually all of the privately operated transit systems in higher-income economies. Their main competition in Europe is from the former, partially privatized municipal transit operators, which are typically allowed to compete with these international firms. To date, most of these firms have been hesitant to move into emerging markets where they are less certain of the risks, though TransDev and a few others have moved into Latin America.

13.2.2.1Service Contracts (Gross Cost)

The Nantes BRT is also operated as part of the gross-cost contract for all public transport services in Nantes. Nantes Métropole built and owns all of the BRT infrastructure and all of the public transport vehicles. The compensation paid to the operator is a fixed amount, agreed upon at the beginning of the contract, based on a specified number of kilometers, and integrates inflation and fare increases (personal communication with Cécile Lairet, 2013). By agreeing to a fixed amount for the life of the contract, the contract provides some protection for the metropolitan area to control costs. The operator collects and keeps all fares collected and is then paid a subsidy on top of that. In 2012, the cost of operating the public transport network was about US$185.2 million (€142.8 million per 2012 rates at USForex Foreign Exchange Services), and fares paid US$64.1 million (€49.4 million, or about 35 percent) of that cost. Nantes Métropole paid US$117.5 million (€90.6 million), and this included social fares (e.g., senior citizens who ride for free). The remaining US$3.6 million (€2.8 million) came from advertising, repayments from insurance, and ticket checks. The operator received about US$9.9 million (€7.6 million) per month from Nantes Métropole in 2012.

The level of service is specified in the contract and measured by fifteen indicators, with a specific level that the operator has to reach for each indicator. An external firm conducts the audits, and if the operator does not reach the required global level, the operator has to pay a penalty to Nantes Métropole. Close financial controls ensure that the Métropole knows exactly what the operators’ expenses are before making payments.

13.2.2.2Route Contract (Gross Cost)

In Las Vegas, compensation for the private operators is based on an hourly per-bus rate of US$53.10. The transit authority, RTC, owns all the vehicles, but the private operator is responsible for operations, maintenance, and all other costs related to public transportation provision other than infrastructure (personal communication with Angela Torres Castro, 2013). The RTC plans the routes and frequency of the vehicles, and contracts a separate company that ensures contract compliance. The contracting arrangement in Las Vegas appears to work well.

13.2.2.3Route Contract (Net Cost)

The R-Net BRT in Amsterdam is an example of a net-cost BRT operation. The collected fare forms the basis of compensation and there is no guarantee for minimum payment for customers. For instance, if no customers are transported, the operator will not receive any payment for customers; if 80 percent of expected customers are transported, the operator will receive 80 percent of the payment, and so on. This also encourages smart pricing to raise revenue.

The Stadsregio Amsterdam, the metropolitan Amsterdam area, calls this arrangement a “supplementation contract.” For example, if a firm offers a “supplementation factor” of 1.4, then for every US$10 million of fare revenue (€9.1 million), the operator receives US$14 million of subsidies (€12.7 million), so that total payment is US$24 million (€21.7 million—figures from 2016 exchange rate of Oanda.com). At tender, operators offered their “supplementation factor.” According to Stadsregio Amsterdam, the result was a self-regulating contract with a focus on raising customer demand.

The Cambridgeshire BRT is also a route contract (net cost). It has two operators with routes that use the Cambridgeshire guided busway, and they both directly collect the fare revenue. As with other BRT systems, the busway was mostly paid for by funds from the central government, though some amount was paid by real estate developers who owned land close to the corridor. Two vehicle operator companies, Stagecoach and Whippet (a subsidiary of Tower Transit that operates buses in London and in turn is a subsidiary of Transit Systems, an Australian firm), both run vehicles on the busway. Both pay an annual fee to use the busway, which covers the county council’s overhead costs related to the busway, including staff, maintenance, and utilities (about US$743,790 or £600,000). The operators are required to provide a minimum hourly service (three buses per hour), and have a five-year contract. Since the busway’s opening, both operators have added services. They collect all fares, and receive no subsidy besides a subsidy for fuel from the central government, and compensation for reduced-fare riders (such as the elderly).

13.2.2.4Design-Build-Operate-Transfer Contracts

The Rouen BRT is operated under a hybrid type of contract that includes elements of a build-operate-transfer contract, a net cost contract, and a gross cost contract. The schedule of services for the BRT in Rouen, known as the Transport Est-Ouest Rouennais (TEOR), is planned and managed by the local government body called Communauté de l’Agglomération de Rouen Elbeuf Austreberthe (CREA). The BRT has three corridors, is 30 kilometers long, and sometimes operates in mixed traffic. TEOR was created as an integrated part of the transport system in the city, which also includes 15 kilometers of tramway, and eight lines of conventional bus service.

The contract for operation of the BRT was part of a special contract with Veolia (now TransDev) that also included construction and operation of the tramway (CREA, not TransDev, paid for the construction of the BRT). Veolia/TransDev won a thirty-year contract in 1994, and it includes operation of the entire public transport system. This contractual form is unusual in France, where such public transport operating contracts are usually only six to seven years long. The authority pays the operator about US$65 million (or €50 million) annually for operation of the system, including tramway, BRT, and conventional buses (personal communication with Catherine Goniot, 2013). The payment to the operator is made on the basis of trips made, kilometers travelled, and customers transported, combining elements of net cost and gross cost contracts. If the operator makes more trips than foreseen, travels over the stipulated amount of kilometers, or carries more customers, CREA’s payment is higher. Other parameters for payment include speed—the faster the trips, the less CREA has to pay. This is an incentive for CREA to reduce congestion. Veolia collects fares, maintains vehicles, while CREA owns the vehicles and depots. There have been some complaints that such a long-term contract, without any quality of service provisions, has led to weaker service.