13.4Competition within the BRT Market

You rarely win, but sometimes you do.Harper Lee, novelist, 1926–2016

After the experience with transit privatization and deregulation in the UK, many experts believed that urban transit services were better off if there was competition “for” the transit market, rather than competition “in” the transit market.Competition “for the market” refers to the tendering out of a set of transit services identified as necessary by a government body. Competition occurs at the time when the services are put up for competitive bid every so many years (usually five to seven years). This had the benefit of ensuring that services were provided according to social needs, while providing periodic leverage over the private operators to improve quality and reduce operating costs. The longer the length of the contract, however, the less leverage the government has over the company once the contract is awarded. After the contract is awarded, that company has a monopoly over the provision of those services until the next tender. If the quality of service is poor, the government has little recourse but to cancel the contract, which governments are generally very reluctant to do as it involves significant disruption of services.

Competition “in the market,” by contrast, traditionally meant ongoing competition for customers for the same set of services. The traditional downside of competition “for in market” was that firms would all tend to compete for the customers on the highly lucrative routes during the peak periods and underserve the times and routes with less demand. It also tended to lead to a lot of customers getting killed at curbside as buses jostled to receive customers first. On the other hand, companies have an ongoing incentive to maintain a higher quality of service as they are competing for the same customers as other companies on an ongoing basis.

When the business model for TransMilenio was developed, the service wanted to retain an element of both forms of competitive pressure. It did so by having more than one company in place to operate BRT services on the same routes, though both companies were paid by the bus kilometer. Having more than one company operating on the same routes, while paying both companies per bus kilometer, created the possibility of having the BRT authority transfer part of the market from one company to its competitor at any time that quality of service began to lag. This gave the BRT authority a lot more leverage over the private operators than in a standard contract where there is only competition “for the market” and no competition “within the market.”

The mechanism for this was to have the BRT authority evaluate on a continuing basis the quality of the service for each company (see next section). If the quality of service for one firm is poorer than for another, the firm providing the poor quality of service will have part of their market taken away from them (the number of kilometers they are assigned to operate) and given to their competitor for one month.

Having multiple operators on a single corridor also significantly increases the chances that a transit authority can make good on a threat to step in in case there is a major problem with an operator. If there is only a single monopoly operator, and the government steps in, operations will stop until a new operator can be found. If there are multiple operators and the government needs to step in, it can immediately give the service and usually the vehicles as well to the competitor to operate the route with minimal disruption of service.

After TransMilenio, a growing number of cities decided to opt for multiple operators on a single BRT corridor, to provide some competition within the market as well as competition for the market.

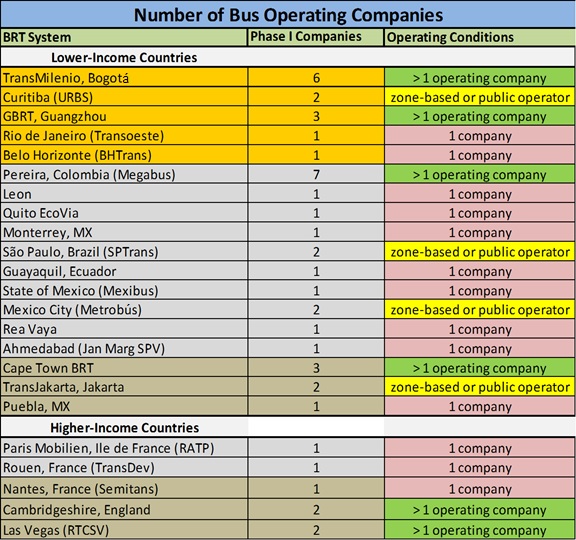

In Figure 13.11, BRT systems are divided into three categories with respect to the degree of competition within the market. Those with Phase I coded green have more than one company able to operate any of the BRT routes. Those coded yellow are either zone-based contracts where there is more than one company operating on some corridors that are between zones, or they are systems where there is a public operator in place to compete with the private operators. Those coded pink are those systems where all routes are served by only one company.

The Colombian BRT systems and those in Guangzhou, Cape Town, Las Vegas, and Cambridgeshire all have private operators that have at least two operators able to operate on the BRT infrastructure. For BRT systems in Curitiba and São Paulo, there are only multiple companies on BRT corridors that pass between zones. In Mexico City’s BRT system, a public operator competes with the private operator on most corridors to provide some competition for the market. For Jakarta’s BRT system, in all the phases after Phase I, there was more than one operator (usually two) on each corridor: one competitively tendered and one given over to the traditional operators, or two given over to traditional operators.

In all the remaining systems, there is no competition “within” the market, with a single firm or consortium providing all the BRT services on a particular corridor.