13.3Competitive Tendering

Goodwill is the only asset that competition cannot undersell or destroy.Marshall Field, entrepreneur, 1834–1906

If it is decided that operations of the BRT are to be turned over to private operators, the next key decision is whether to competitively tender the operating contracts, or to turn them over to a new or existing firm through some other administrative mechanism.

There are several reasons to make the awarding of BRT operating contracts subject to competitive bidding:

- The city is likely to pay less for the service;

- It gives the government more leverage over the remaining (non-cost) details of the contract in the negotiations;

- It is a requirement of many government procurement rules;

- It is in compliance with most development bank loans, thus opening up more financing options;

- It allows the government to stay in control of the timeline;

- It ensures that the companies that operate the system are the best companies possible;

- It can play a critical role in operating company formation.

In cities where operating contracts were negotiated, negotiations dragged on, significantly delaying the start of operations, as the city had no clear and simple way to compel a closure to the negotiations. From the perspective of company formation, the competitive tender approach allows the city to establish the minimum qualification criteria for eligible companies in the TOR for the tender. These minimum qualification requirements force the bidders to create companies that are sufficiently capitalized, that have a clear governance structure, and that have a qualified staff. Ultimately, it helps the companies become regionally competitive in the long run. It gives these cities much greater leverage over the negotiating process to ensure that companies were formed following a government-established timeline. It also ensures that the contracts were awarded to the best possible companies.

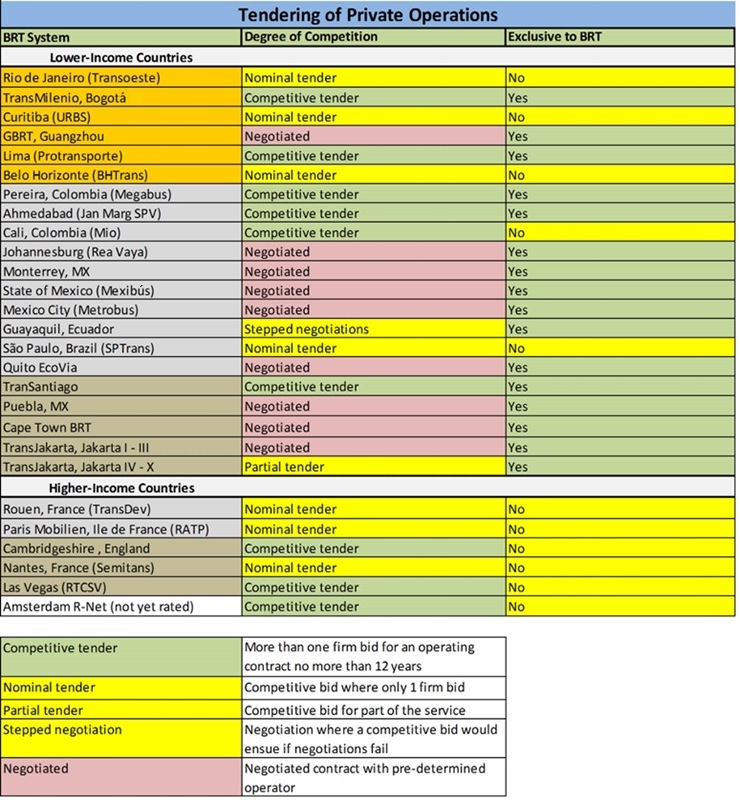

In general, tendering out of municipal BRT vehicle operations is rarely fully free and competitive. The degree of competitiveness, however, can have an important impact on the ultimate quality of service. Figure 13.7 ranks several leading BRT systems in terms of the degree of competition in their tendering process. Those contracts where there was a reasonably robust competitive tender with more than one bidder and some real competition are shaded green. In these cases, governments tended to negotiate for lower operating costs and more private investments, and require more quality of service guarantees. The maximum length of the contract included here is twelve years. European Union rules allow for a maximum contract life of ten years, but it is typical in some Latin American systems to extend the contracts for twelve years. Both of these types of contracts are set to mirror the expected reasonable commercial life of the vehicle so that investors can recoup their investment in the vehicle.

Those contracts that were awarded with less than full competition were shaded yellow. This included a number of possible cases. In all cases the government had some leverage over the private operators during the negotiation to require lower costs, more investments, and some quality of service guarantees. But the government had a generally weaker hand in the negotiation than in the case of full competitive tenders. This includes cases where a competitive tender was held but where only one firm ended up bidding (French and Brazilian cases), or where the period of the contract is greater than twelve years (Rouen). It includes cases where only a part of the service was competitively tendered, and the remaining part of the service was negotiated (Jakarta). Finally, it includes cases of a “stepped negotiation” where the government agrees to negotiate with a particular firm or consortium, but the government sets conditions in advance that require turning to a competitive tender if the negotiations break down (Guayaquil).

Those cases where BRT operations were awarded to a firm without a tender, usually a negotiation with a consortium of the former operators in the same corridor, are coded pink. In almost all of these cases, the leverage of the government over the private operator, to compel better services and lower costs, is considerably weaker.

13.3.1Competitive Tendering in Lower-Income Economies

13.3.1.1Managed Competitive Tendering of BRT Operations

Bogotá’s TransMilenio initiated a significant increase in the level of competitiveness in the tendering process of Latin American BRT systems, which later spread to other cities around the world. Competitive tendering specifically of new BRT services was first done in Bogotá, and later spread to other Colombian cities, and to Lima, Santiago, and Ahmedabad. The companies that won these tenders were stronger companies as a result, and many of them have gone on to become regionally if not internationally competitive. These systems were colored green for having a reasonably competitive tendering process.

A competitive bidding process ensures that firms offering the best quality and most cost-effective services are invited to participate in the new BRT system. A bidding process can also do much to shape the long-term sustainability of the system. Competition is not just reserved for trunk line operators as other aspects of a BRT system can also benefit, including feeder services, fare collection systems, control center management, and infrastructure maintenance.

A bidding process sets expectations for the private entities interested in being part of the system and establishes the terms and conditions that will define the relationships among the different actors. The bidding process developed by Bogotá’s TransMilenio stands out as one of the best examples of providing a competitive structure directed at both quality and low cost. In reality, Bogotá used its incentive structure to achieve a variety of objectives:

- Cost-effectiveness;

- Investment soundness;

- Risk allocation;

- Environmental quality;

- Opportunities for existing operators;

- Local manufacturing of vehicles;

- International experience and partnerships.

Bogotá’s competitive bidding process provided the incentives to completely modernize its public transport system by encouraging modern vehicles, wider company ownership, and sector reforms. The principle mechanism in Bogotá was the use of a points system to quantify the strength of bidding firms. By carefully selecting the categories and weightings within the points system, TransMilenio shaped the nature of the ultimate product. Table 13.2 provides a summary of the bidding categories and weightings.

Table 13.2Points System for Bidding on TransMilenio Trunk Line Operations

| Factor† | Description | Eligibility | Points:Minimum* | Points:Maximum** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal capacity | Bidding firm holds the appropriate credentials to submit a proposal | X | - | - |

| Economic capacity | Bidding firm holds the minimum amount of net owner’s equity to submit a proposal | X | - | - |

| Passenger public transport fleet in operation | 30 | 140 | ||

| Experience in operation | Specific experience providing passenger services in Colombia | 50 | 250 | |

| International experience on mass public transport projects | 0 | 50 | ||

| Economic proposal | Offer price per kilometer to operate the service | 0 | 350 | |

| Right of exploitation of the concession | ||||

| Proposal to the city | Valuation of the share given to TransMilenio SA from the revenue of the concessionaire(1) | 21 | 50 | |

| Valuation of the number of buses to be scrapped by the concessionaire(2) | 14 | 50 | ||

| Composition of equity structure | Share of company’s stock held by former small vehicle operators | 32 | 200 | |

| Environmental performance | Level of air emissions and noise; disposal plan for liquid and solid wastes (1) | 0 | 200 | |

| Fleet offered | Size of fleet; ; | X | - | - |

| Manufacture origin of the fleet; ; | 0 | 50 | ||

| Total (1350 points possible) |

† If the proposal meets all the requirements, then the proposal will be categorized as ELIGIBLE.

* If the proposal is below any given minimal value, then the proposal will be categorized as NOT ELIGIBLE.

** If the proposal does not meet the established range, then the proposal will be categorized as NOT ELIGIBLE. (1) Not present on first phase; (1) Fixed number on first phase.

The “economic capacity” category refers to the ability of the company to provide a minimum equity level as an initial investment. The minimum equity level is equal to 14 percent of the total value of the vehicles being offered to the system. The minimum owner’s equity is defined in Equation 13.1:

\[\text{Minimum Owner's Equity}=\operatorname{NMV}\times\,\text{US\$200,00}\,\times14\%\]

Where \(\operatorname{NMV}\) is the maximum number of vehicles offered to the system.

The value of US$200,000 was the approximate cost of an articulated vehicle in Phase I of TransMilenio, based on the specifications required by TransMilenio SA.

The points system was used in a way that rewarded inclusion of the existing operators, but the design also provided an impetus to consolidate small operators into legitimate companies.

The “environmental performance” of the bid refers to the rated air emissions and noise levels expected from the provided vehicle technologies as well as the expected handling of any solid and liquid waste products. In the case of Bogotá, the initial minimum standard for tailpipe emissions is Euro II standards. With time, this requirement will increase to Euro IV. However, firms offering Euro III technology or higher can gain additional bid points for doing so. The bidding process thus offers an in-built incentive to not only meet minimal standards, but encourages firms to go much higher. In turn, this incentive creates a dynamic environment to push vehicle manufacturers to provide improved products. Prior to TransMilenio, Euro II technology was difficult to obtain in Latin America since the manufacturers produced such vehicles predominantly for the European, North American, and Japanese markets. Now, with the incentives from TransMilenio, some manufacturers in Latin America are even producing Euro III vehicles.

The bidding process also encourages the vehicle manufacturers to develop fabrication plants in Colombia. Local fabrication of vehicles is awarded additional points. This item is not a requirement, but it does bring benefit to bidding firms that can secure local fabrication. Thus, the bidding process does not require local manufacturing in a draconian manner. Instead, the positive reinforcement of bidding points helps to instill a market-based outcome. To date, much to the credit of TransMilenio’s existence, two major international bus manufacturers have established production sites in Colombia. Marcopolo, in conjunction with two local firms, has built a fabrication plant in Bogotá (Figure 13.8), while Mercedes has built a plant in the Colombian city of Pereira.

Bogotá’s competitive bidding process has been successful in selecting operators who are most capable of delivering a high-quality product. Table 13.3 summarizes some of the characteristics from the successful bids for Phase II trunk lines of TransMilenio.

Table 13.3Successful Bids for Phase II Trunk Lines of TransMilenio

| Company name | Fleet size | Emissions | Price / kilometer (Colombian pesos) | Revenues* to TransMilenio (percent) | Vehicles to scrap | Participation of existing operators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owners | Percent of equity | Owners | Percent of equity | ||||

| TransMasivo SA | 130 | Euro III | 3,774 | 3.53 | 7.0 | 452 | 20.22 |

| Sí – 02 SA | 105 | Euro II | 3,774 | 3.53 | 7.5 | 658 | 21.62 |

| Connexion Mobil | 100 | Euro II | 3,774 | 3.53 | 8.9 | 740 | 29.39 |

Source: TransMilenio SA

* The “Revenues to TransMilenio” column represents the amount of revenues that the bidding firms are willing to give to the public company (TransMilenio SA) in order to manage the system.

The successful bids in Table 13.3 indicate different strategies by each firm. Interestingly, all firms entered the same price level and the same sharing of revenues to TransMilenio. The selection of these values is not due to collusion or coincidence. Instead, these values are the median of the allowed range. The column “vehicles to scrap” indicates the number of older vehicles that each company is willing to destroy for each new articulated vehicle introduced. Thus, for example, the company “Connexion Mobil” will destroy 8.9 older vehicles for every new articulated vehicle that the firm purchases. With a total of 100 new vehicles being introduced, Connexion Mobil will thus destroy 890 older vehicles. The final columns set out the amount of participation each firm has given to existing small operators.

The second phase incorporated many additional requirements for the operators, but these additions did not discourage interest or reduce the value of the bids. The initial bidding process had many uncertainties and risks that did not hold with the second.

The duration of the concession contract has also played a pivotal role in influencing the results of Bogotá’s bid process. A long concession period increases the value of the contract and thus increases the quality and quantity of the bids. However, if the concession period is too long, then the municipality’s flexibility with future changes becomes limited. Further, a long concession period can have a negative effect on competition since it creates a long-term oligopoly for the successful firms. In the case of Bogotá, the duration of the concessions matches the estimated useful life of the new vehicles. Each successful firm thus receives a concession for ten years.

The ten-year concession period (based on kilometers) also applies to the feeder services. During Phase I of TransMilenio, the feeder operators only received a concession for a period of four years. The trunk operators still had a ten-year concession during Phase I. The longer concession in Phase II for the feeder companies reflects increased expectations for these firms in terms of vehicle technology and service quality. By giving a longer concession period, the operators can purchase new vehicles and amortize the vehicles over time. After Bogotá developed this form of managed competitive tendering, it was copied in a number of other cities, particularly other cities in Colombia, but also in Lima, Santiago, and Ahmedabad.

13.3.1.2Nominal Tenders: Periodic Tendering of Area Contracts and Staged Negotiated Contracts

BRT started in Brazil. In most Brazilian cities, the history of tendering vehicle operations is similar in all cities. In almost all Brazilian cities, a set of private vehicle operators established control over an area of the city, and this control was legitimized in law with an area contract—either a gross cost or a net cost contract. In the past decades, federal law has required the retendering of route licenses after a maximum number of years. During the periods when these area licenses are re-tendered, the municipality has some leverage to demand more out of the vehicle operators. Usually this leverage is used to require them to buy new vehicles or improve other elements of their service. While inevitably the historical operators have tended to win a renewal of their contract, this period when the contract expires has given the government more leverage over the operators to demand more. For all of the Brazilian systems, the operating contracts have not been tendered upon the initiation of a BRT system, but rather they have been tendered during their periodic contract renewal phase for their area contracts (whether gross cost or net cost). As such, all of the Brazilian BRT systems have been colored yellow, to indicate that there is some nominal tendering in the awarding of contracts.

Guayaquil in Ecuador used the threat of moving to a fully competitive tender to improve its negotiations with its operators. Guayaquil’s Metrovía system has been developed around a tiered approach to operator contracting. The Metrovía oversight organization set certain standards that any concession agreement must reach. Existing operators in the city were given first right to participate in the concession. If the operators did not accept this opportunity, then the second tier of opportunity would be extended to firms operating within the province. If the system was still not fully subscribed after the second tier, then the operating contracts would be opened to all national and international firms in the final tier. Given the impending presence of other firms entering their market, the existing operators agreed to terms with the city and thus filled the operating quota for the project’s first phase. This gave the municipality significant leverage over the traditional operators, which still won the bid, but the Guayaquil operators have not gone on to become regionally competitive companies in the same way that the TransMilenio operators have.

In the case of TransJakarta, the DKI Jakarta government decided in Phases III and IV of the project that as they were investing roughly 60 percent of the total project cost in the form of infrastructure (as compared to 40 percent of the total cost required to buy new vehicles), that 60 percent of the market share would be put up for competitive tender and the remaining 40 percent of the market would be turned over to a consortium dominated by the traditional operators. The company that won the tender was an intercity vehicle operator that could offer a low-cost service per kilometer. Never compelled by the minimum qualification criteria of a competitive tender, the traditional operators never completed the process of transition to modern vehicle operating companies, and most continue to struggle with performance and maintenance issues and low quality of service. The services offered by the winner of the tender have tended to be better.

13.3.1.3Negotiated Operating Contracts Around the World

In many other countries, particularly in South Africa, Mexico, and Ecuador, municipal governments never required a real competitive tender. In South Africa, the existing minibus industry in South Africa has done much to promote Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) in the country and has served a key historical role in providing transport services to marginalized communities. It was an industry composed of small individual owners consolidated into various competing taxi associations. The structure of the industry was so complex and labor relations so volatile, that the South African government decided to use provisions in its public procurement law that allowed for noncompetitive bidding in the case of black empowerment goals. In the end, South Africa decided to negotiate with the existing affected operators. Thus, the government partially achieved some of its small business development and black empowerment objectives. It did this at a very high cost, with operating costs being as much as 40 percent higher than what would have resulted from a competitive tender.

On Quito’s Ecovía corridor, the existing operators formed a joint consortium (called TRANASOC) and were given exclusive rights to provide services for a ten-year period. The operators were also essentially given free financing on the new articulated vehicles since the municipality purchased the vehicles with public funds.

In Quito, the operators were to repay the municipality for the vehicles using revenues collected from the system. Unfortunately, fare collection was done directly by the operators so the municipality has little knowledge on actual customer counts and revenues. Quite worryingly, the operators’ repayment of the articulated vehicles was tied to profit guarantees related to the number of customers. Clearly, the operators had a strong incentive to underestimate customer and revenue numbers to minimize any repayment of the vehicles. In the end, the city simply sold the vehicles to the operator at a greatly reduced price.

In Mexico, virtually all the BRT systems were turned over to consortiums of former operators through a process of negotiation, except in a couple of instances. In these cases, there was a powerful intercity vehicle operator that organized the affected operators, offered to manage the new system, and offered to let them join their own company as shareholders. Virtually all the other BRTS in Mexico are operated by corridor-level monopolies created by the former owner/operators.

León’s BRT structure is likewise skewed toward rewarding existing operators rather than overall efficiency. Like Quito, existing operators formed a monopoly consortium, in this case called the “Coordinadora de Transporte.” The municipality acquiesced to the consortium’s demands for full monopolistic rights of operation. The consortium’s operating rights to the system do not have a termination date, implying a monopoly in perpetuity. However, on the positive side, the consortium did invest directly in new vehicles.

Besides the lack of transparency and competitiveness within the system, the market design also has negative consequences for quality of service. Given the predictable results of manipulation and inefficiency, why do municipalities choose uncompetitive structures such as those in Quito, León, and Jakarta? Principally, the reason is a lack of political will. Municipal officials are not willing to entertain the possibility that some existing operators could lose their operational rights along a particular corridor. The resulting upheaval from disgruntled operators could have political consequences. If a BRT project is faced with no other option than to proceed with a negotiated contract with an existing operator, there are still ways to optimize the results.

13.3.2Competitive Tendering in Higher-Income Economies

In higher-income economies, if there are private operations, then some sort of competitive tendering process is generally required by public service procurement rules, including the European Union’s rules on public transport procurement. In the best-case scenario, there is a robust tender with many firms bidding for the BRT services and usually other public transport services. In the worst-case scenario, a competitive tender is held to comply with EU requirements, but it is a foregone conclusion that the current operator will win, and there is only one bidder.

Some reasonably competitive tenders for BRT operators in higher-income economies include the Las Vegas SDX, the Amsterdam R-Net, and the Cambridgeshire guided busway. Some less competitive BRT vehicle operations include the Rouen, Paris, and Nantes BRT systems in France.

Public transportation in Las Vegas has for many years been operated by private companies. It is managed by the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada (RTC). Since the RTC was created in 1992, all public transportation in Las Vegas has been operated by private firms that were contracted through RFPs. Previously, public transport was operated by a single firm (Veolia), with another firm (First Transit) providing “paratransit” services. Because administrators felt the system was too large to be covered by a single contract, a new tender (or RFP) was held, and two winners, Keolis Transit America and MV Transportation, were announced in February 2013 (Velotta, 2013).

Public transportation in the Amsterdam metropolitan region is split into four zones, all of which are tendered. While the operating contract for the central region (Amsterdam proper) has been continually won by the public operator GVB, which, as per the GVB website, has operated the system for over 113 years, the area of the R-Net (previously known as Zuidtangent) is operated by Conexxion (owned mostly by TransDev), which won a competitive tender for eight years.

The Nantes BRT is operated by Semitan. It won a competitive tender for a six-year contract, but Semitan was the only bidder, and it was the former public transport operator in the city of Nantes. In Rouen, the BRT system is operated by TransDev (formerly Veolia), which won a thirty-year operating concession as part of a long-term design-build-operate contract that included building a tramway and operating the entire municipal public transport system. It won a competitive tender but the length of the contract undermines the leverage of the regional government over the private operator.