13.1Private BRT Operations

There are two types of stories: public and private.Antonio Muñoz Molina, novelist, 1956–

All BRT systems have basic functions that need to be handled by either private companies under contract to a government authority or by a department or branch of the government itself. The critical functions include:

- Vehicle operations;

- Fare collection;

- Station management;

- Trust fund management;

- Control center management;

- Scheduling.

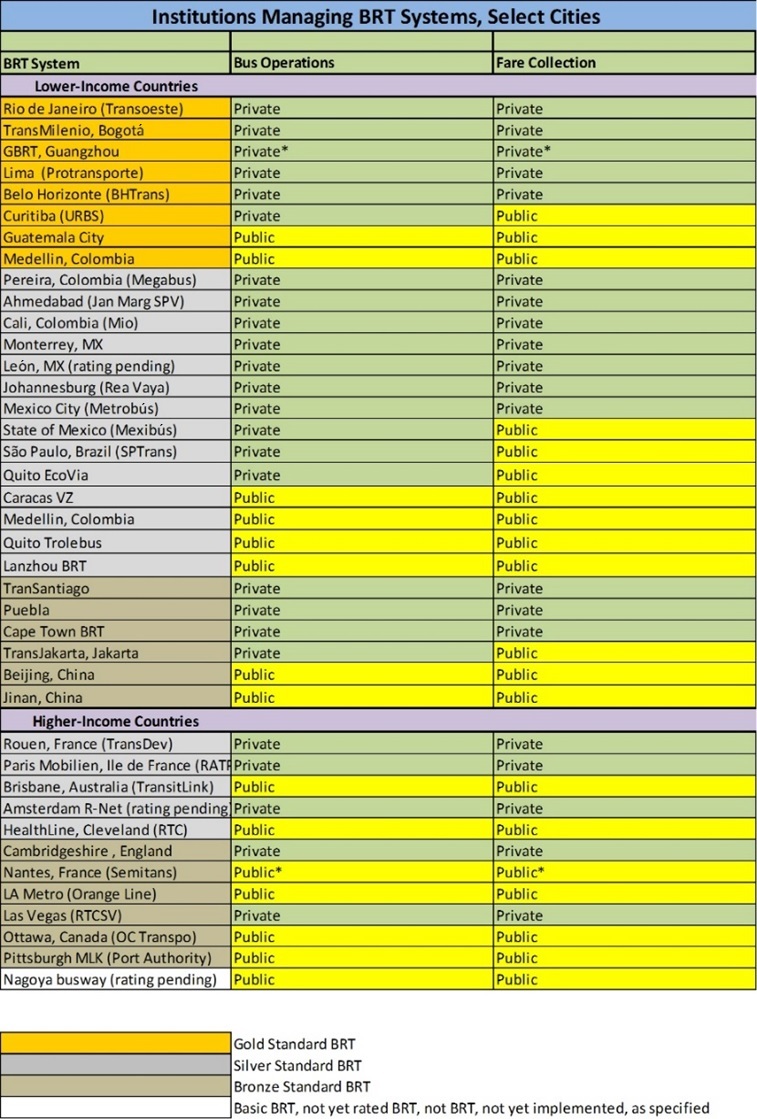

Figure 13.1 shows whether different well-known BRT systems around the world contract out the operations of the two most critical functions, vehicle operations and fare collection systems. Although there are examples of BRT systems with well-managed public operations, particularly in higher-income economies, the emerging consensus is that private operation of the fleet of vehicles and the fare collection system tend to lead to better quality of services, if the contracts are written and supervised properly.

13.1.1Private Contracting of BRT Operations in Lower-Income Economies

In lower-income economies, the degree and nature of private sector contracting of BRT services is quite different from that in a higher-income economy. The administrative form of a transit authority or transportation authority is largely unknown. The vast majority of BRT systems in lower-income economies are operated by private companies. The exceptions are those systems operated by a public bus monopoly (Chinese BRT systems outside of Guangzhou), by a former public bus monopoly that remains in control of part of the market (Mexico City’s RTP and Delhi’s DTC), the systems operated by public metro companies (Medellín and Caracas), the electric Trolebús BRT in Quito (subsequently privatized), and the Guatemala City BRT. All of these systems are operated by publicly owned companies, not transit authorities. BRT vehicle operations in all the other cities of lower-income economies are operated by private companies.

The same holds true for most of the fare collection systems, with the exception of some of the better BRT systems in Brazil (Curitiba, São Paulo), TransJakarta, and some of the Mexican systems where problems with the private operator require the government to step in. In Curitiba and São Paulo, fare collection is managed directly by the transit authority (SPTrans in São Paulo and URBS in Curitiba). In some cities in Brazil, private transit operators ceded control over fare collection over time to public authorities (though never in Rio or Belo Horizonte). This has been relatively unproblematic.

In the case of Puebla, Mexico, the fare collection service provider was so poor it had to be replaced by the BRT authority. In the case of the State of México, the infrastructure service provider originally also collected the fare as part of a PPP deal, but the system could not cover the cost of the infrastructure, so the state had to take control of the infrastructure and step in to control fare collection. In the case of TransJakarta, the fare collection system was initially primarily a paper fare system (the original smart card rarely functioned), and was managed in-house by TransJakarta, a weak public authority. The fare collection system had numerous operational problems and the system’s revenues were notoriously non-transparent. Eventually the fare collection system was taken over by a consortium of six national banks. Transparency of the system improved as paper ticketing was stopped and all transactions were recorded as smart card transactions, but a weak contract with the consortium led to the loss to the public authority of most of its control over fare policy.

The decision about whether the public sector can directly manage the fare collection system of a BRT system is somewhat based on whether the government is strong enough and has the administrative capacity to take control of the fare collection process from private operators. It also depends on the degree to which the vehicle operators and their bankers trust the government to honestly report fare revenue and pay them. In many BRT systems, the private vehicle operators turn to private banks to borrow money to buy the vehicles. The only guarantee that these private operators have that they will be able to repay the loan is their operating contract with the government, which promises to pay them. If the government is trusted by the bankers to pay them, then there is no fundamental problem with having the government directly collect the fare revenue; however, there is such rapid progress in fare collection system technology that it may not be easy for a government body to keep pace with innovation.

In lower-income economies, private contracting of BRT vehicle operations generally means that the procurement of the vehicles is done by the private operating company. This has a few distinct advantages in the lower-income economy context. First, public vehicle procurement in lower-income economies often invites corruption. Too often public officials, given the power to make a multi-million dollar procurement decision, will base this decision more on the basis of illicit payments than on the technical merits of the bus. Second, public officials rarely know as well as a private vehicle operator what sort of vehicle will be the most efficient or appropriate for a given service. Third, public procurement of the vehicles sometimes leads to litigation. If a private operator is forced to operate a vehicle that was procured by the government, and the vehicles face significant problems, it is unclear whether the responsibility for the breakdown of the vehicles is the fault of the private operator or the government that made the procurement. Fourth, a private company is more likely to diligently protect the vehicles and properly maintain them if it owns the vehicles than if it operates them on behalf of the government.

In all but a few cases, where a BRT vehicle operator is private, the private operator bought the vehicles. The only exceptions to this are in Cape Town, Jakarta, part of the fleet in Mexico City (the part operated by RTP, the public operator), and part of the fleet in Guangzhou. In some cases, it is easier to financially ring-fence the BRT system. These include situations in which a BRT system is unable to cover its operating costs, and where it violates public procurement rules to have a government buy the vehicles then turn the ownership over to a private operator (as is the case in South Africa). In these situations it helps to have the government close an operating budget gap by buying the vehicles and turning them over to the operator over time in a lease-to-buy arrangement, rather than having the private operator buy the vehicles and then be paid on a gross cost basis.

Many BRT systems have been experimenting with contracting out more and more of the functions of the BRT system as a way of avoiding the bureaucratization of these functions. TranSantiago contracted out the operational control system and operational planning as well. TranSantiago noticed the growing numbers of staff in the operations division of TransMilenio, despite a lack of improved services, and wondered if it would not do better contracting out operational controls and operational planning. These functions both require highly technically skilled staff, who are difficult to retain. There is also a lot of innovation in this area. Contracting out these functions intelligently to firms with expertise in public transport system optimization is likely to prove to be a win-win proposition.

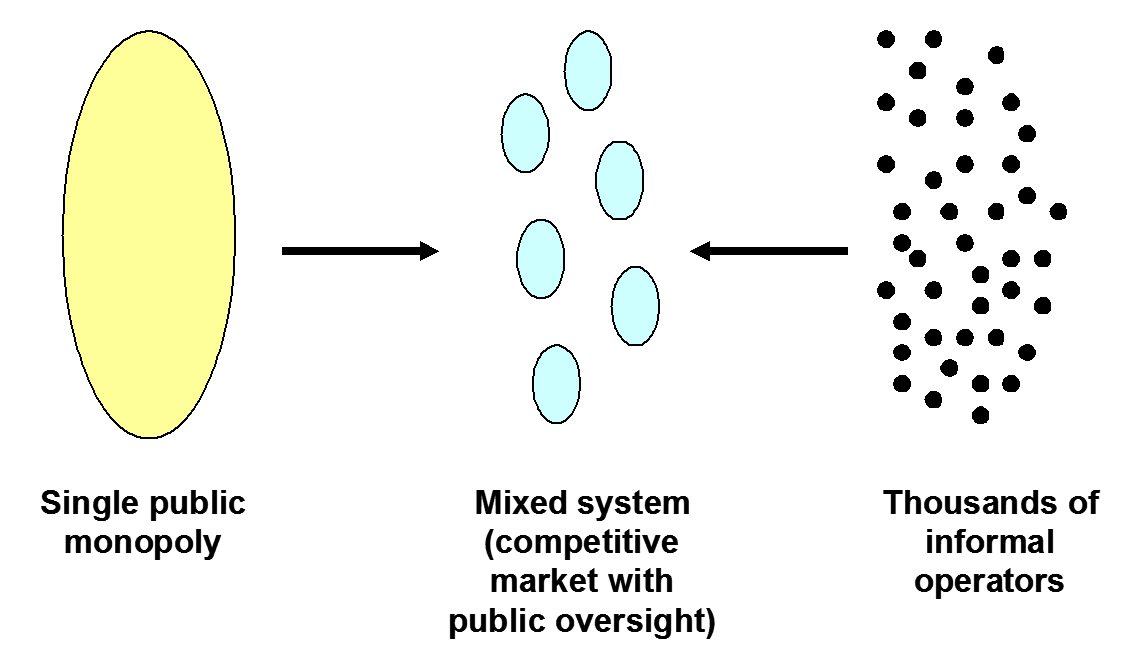

In lower-income economies, there is a long history of privately owned, poor quality public transport services in which municipal governments use public companies to try to improve the services. This leads to these public services encountering a number of problems, with most of them ultimately failing. These are then replaced with either private, zone-based bus concessions or private, largely informal route concessions. Informal bus and minibus route licensed services survive largely without subsidy but there is generally public dissatisfaction with the quality of service. The competition for customers at curbside frequently leads to unruly behavior and fatalities. Services rarely adhere to a predictable schedule or set of predictable stops. Additionally, the vehicle fleets tend to be old and highly polluting, weakly insured or uninsured, and not particularly roadworthy. Services tend to be divided up into territories that force needless transfers on customers.

In Latin America, BRT was frequently used as leverage to bring about public transport sector regulatory reform, moving from either weakly regulated, informal operators or a dysfunctional public vehicle operating monopoly to a form of well-run, well-regulated private operating companies.

BRT systems first emerged in Latin America, where in many cities they played a central role in this regulatory transformation. As in higher-income economies, private trolley and tram concessions and later bus concessions dominated the Latin American cities from the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries into the 1940s.

In Brazil, BRT and regulatory transformation mostly occurred separately. In São Paulo the tram network was built by a Canadian investor with a franchise. The municipality cancelled the franchise in the early 1940s and turned the assets over to a newly created municipally owned company, CMTC (Companhia Municipal de Transportes Coletivos). CMTC introduced trolleybuses to São Paulo as well as normal buses, and it was the main bus and trolleybus operator in São Paulo until it was broken up and privatized in the early 1990s in the aftermath of the Latin American debt crisis. What emerged in the aftermath of the privatization was similar in form to what had existed in Curitiba and other Brazilian cities since the 1960s: zone-based concessions. In Curitiba, Rio, and other cities that implemented BRTs, these operated without municipal subsidies, but fares were high. In São Paulo, they operated with subsidies and fares were lower. As they controlled entire zones of the city, reasonably large vehicle operating companies entered the market. When Curitiba, Rio, Belo Horizonte, and São Paulo opened their BRT corridors, all of them turned over the operation of the BRT corridors to the same private vehicle operators that already controlled vehicle operations in that part of the city.

In other parts of Latin America, however, the BRT projects were instrumental in modernizing the contractual structures of the private bus industry. Mexico City had private route concessions until 1980. In 1980 the head of the Federal District analyzed the status of all the route concessions and created a much bigger municipal vehicle operator to take over the poorer quality routes. It was called Ruta 100, and it survived until 1995, when it went bankrupt. It was broken up, partially privatized, and part remained under a new public vehicle operator, RTP. With the collapse of Ruta 100, a few routes survived under public control of RTP, but most of them went back to operating as route franchises with small owner operators, with the majority of them only owning one or two vehicles. When Metrobús started in Mexico City, operations were divided between RTP and a new firm formed of the collective that controlled the route licenses on the BRT corridor. The creation of each new BRT corridor has been used to create a new company, and some of these companies have formed ties with intercity vehicle operators to become regionally competitive firms.

In the rest of Latin America there were also attempts to introduce municipally controlled vehicle operating companies out of dissatisfaction with declining privately provided services. Most of these public efforts had failed by the mid-1990s. In the vast majority of other Latin American cities, route licenses predominated. Small, informal, and independent owners and operators with individual route licenses rose up or took the place of the former municipal operators. In most of Colombia, the route licenses were dominated by a small number of bus “enterprises” that did not own vehicles. Their primary economic asset was a cozy relationship with municipal departments of transportation that controlled route licenses, and the ability to enforce their route monopolies. When BRT was introduced into most Colombian cities (except Medellín), the BRT was used to force these private operators to form new, modern, competitive private companies. Most of them were constituted primarily from the bus enterprises that owned the licenses, and the former affected bus owners, but many joined with larger firms to create regionally competitive companies. Some of these firms are now active in other parts of Latin America.

BRT in Johannesburg and Cape Town has played a similar role, though the process is far from complete. Under the apartheid government, provincial governments contracted out heavily publicly subsidized public transport services to white-dominated private contractors who offered a fairly low level of service. These were long-term cost-plus contracts heavily subsidized by the provincial government. In Johannesburg the Gauteng was contracted out to Public Utility Transport Corporation (PUTCO), and the Western Cape Province contracted out to Golden Arrow. As these services were poor and did not fully serve the ever-sprawling townships, and as black South Africans were not allowed to operate legal businesses, many invested in small minibus taxis. These minibuses were reasonably well regulated in Cape Town, with route licenses; in Johannesburg they were weakly regulated. Though there was a similar nominal route licensing scheme in place, most of the minibus taxis operated without a route license. In Johannesburg, in frustration with the poor quality of PUTCO services, the municipality started its own vehicle operating company, Metrobus. When BRT was established in South Africa, operations were contracted out to new companies composed of the former affected minibus taxis and/or the former private vehicle operators if their routes were affected. It is too early to determine whether these firms will thrive and provide a good quality of service: they have been hampered by labor unrest.

In the rest of Africa, prior to liberation, many major African cities had monopoly bus services privately provided by a major bus manufacturer from the colonial power that ruled the country. Renault, for instance, tended to provide bus services in much of Francophone Africa. After liberation, most of these bus properties were nationalized, but lacking experience in managing vehicle operations, short on money, and with weak governance structures, most of these public vehicle operations collapsed. There are sporadic attempts to resurrect these companies. The cities of Africa also came to be dominated by small individual owner-operated minibuses, and as the countries have gotten richer, these minibuses are sometimes traded up for larger vehicles. Sometimes they operate with route licenses, and sometimes there is no government regulation at all, and informal forms of regulation dominated by unions or quasi-mafias manage public transport operations. These bus and minibus operating companies rarely own more than a few vehicles, and integrated fleet management is largely unknown. As BRT is being introduced into Africa, it is still unclear how the operating companies will be formed. In Lagos, which has a system that is not a full BRT, the former cooperative that controlled the private minibus routes took control of operations, and the operations have been of relatively poor quality. In Dar es Salaam, DART had not begun operations as of this writing, but it is likely that a consortium of the formerly public but now privatized municipal vehicle operating company Usafiri Dar es Salaam (UDA), and two private minibus (Daladala) associations together with a foreign investor who can bring management expertise, will become the operator.

In Jakarta, throughout the Suharto years, private bus and minibus concessions were made. There were bus companies, but they primarily owned fleets of buses and bought licenses from the DKI Jakarta government and then leased the vehicles to individuals to operate and collect the fare revenue. There was a poorly run but very low-cost national government owned vehicle operator in Jakarta, Perusahaan Pengangkutan Djakarta (PPD) that remained in operation. When TransJakarta opened, Governor Sutiyoso forced the creation of a new company from the former private bus owner associations, PPD, and a municipal taxi company. Later corridors had operators formed from existing vehicle operating companies (most are leasing companies), or intercity vehicle operators.

In India, the Delhi High Capacity Bus System has two types of operators: those operated by the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) and private individual informal operators licensed to operate on the routes with BRT trunk infrastructure. Most of India has large, subsidized monopoly public vehicle operating companies, but most of the BRT systems in India are operated by special purpose vehicles (SPVs). Ahmedabad’s BRT is operated by a private company that won an open tender; it was not a former vehicle operator but ran a trucking business.

The Quito Trolebús was for many years operated by a government company. The government initially intended to privatize it, but due to the escalation of electricity prices after the privatization of the electric company the government found it difficult to privatize. Eventually it was able to offer it to a private concession. The Ecovía lines in Quito were intended to be privately operated, but operations were so poor the government had to retake control of the operation, only to return it to private control a few years later.

Thus, in most lower-income economies, BRT has been central to efforts to modernize the contractual relationships through which public transport services are offered to the public. The construction of infrastructure that creates a highly efficient and highly profitable operating environment gave these cities new leverage to renegotiate their relationship with largely private operators, and to get a better deal for their citizens.

13.1.2Private Contracting of BRT Operations in Higher-Income Economies

In higher-income economies, half of the BRT vehicle operations and fare collection systems are operated by the public sector, and half are operated by private contractors. Public sector operations dominate in the United States, Canadian, and Australian BRT systems, while private contracted operators predominate in Europe. Where the vehicles are operated by the public sector, the fare collection system is also always then operated by the public sector, as are most key elements of the BRT system. If the vehicles are operated by the private sector, most frequently the fare collection system is also operated by the private sector. Usually, but not always, fare collection is handled in higher-income economies by the same company that operates the vehicles.

In higher-income economies, it is more common for the vehicles to be procured by the public sector and then maintained and operated by the private contractor, than it is in lower-income economies. This is somewhat less problematic in higher-income economies as there are frequently fewer vehicle procurement options, there is less corruption in the public procurement process, and since vehicle procurement in higher-income economies is almost always subsidized by the government it is sometimes easier contractually to have the public sector buy the vehicles.

The introduction of a BRT in higher-income economies has rarely if ever led to significant innovation in terms of the degree or form of private contracting, though the idea has been discussed. Generally, privatization of services occurred independently of the emergence of BRT systems.

In the United States (Cleveland, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Eugene) and Australia (Brisbane), a public transit authority directly operates the vehicles that operate on their BRT systems. In Canada the vehicles on the Ottawa BRT are operated by a municipal department (Ottawa). In Europe, Cambridgeshire, Rouen, Amsterdam, Nantes, and Paris all contract out their BRT operations (as well as other public transport services at the same time), though Nantes is operated by a company that is majority public sector owned and used to be the public sector transit operating company of the city. In the United States, only Las Vegas contracted out its vehicle operations, including the BRT routes, first to one and most recently to two private firms.

While there is a clear trend toward privatization in Europe, there is a less pronounced trend toward private operation in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Curiously, Brisbane and Los Angeles contract out some of their vehicle operations to private companies, but not the routes that serve the BRT systems in these cities.

This gradual shift to private operation of vehicles in higher-income economies is in some ways a return to the past, but under different contractual forms. In the United States, bus transport was almost exclusively provided by private, for-profit monopoly franchises. This began to change in some cities in the 1950s but many continued in private hands into the 1970s. These monopolistic bus companies, many of them owned by General Motors, were franchises licensed by the municipality, and none of them were subsidized. Initially, they successfully competed with older streetcar systems, and many of them purchased and then dismantled competing streetcar lines. In the 1940s, most of the major United States municipalities took over their remaining streetcar and rail systems that had collapsed financially, and bus systems remained viable for-profit concerns in private hands. After World War II, however, mass suburbanization killed public transport ridership, and annual public transport trips dropped from thirty-five billion to twelve billion from 1945 to 1958 (J. Teaford, 1990). As such, private vehicle operators soon followed the same decline as the tram systems, and by the 1970s virtually all cities had taken over direct operation of their bus systems (Frick, Taylor, and Wachs, 2008). In the United States, some level of privatization began again in the 1980s, and by 2001, over one-third of all agencies in the National Transport Database reported contracting for some services (H. Iseki, 2004). These are not the subsidy-free franchises of old; virtually all of these contracts are public service contracts where the services are determined by the government, the assets are owned by the government, and the service is heavily subsidized by the government.

Public vehicle operation in Europe is older, and the shift to private operation also began earlier. In Germany, public transport firms have been publicly owned and operated since the 1920s (Buehler and Pucher, 2012). A wave of privatization began in the UK in the mid-1980s, and in Scandinavian countries in the late 1980s, becoming more widespread beginning in the 1990s. European Union directives on public procurement from 2007 and 2009 further reinforced this trend toward privatization and made it more transparent by requiring the tendering of all public services above US$161,000 (€125,000). Thus, even where public operators are still functioning, they must compete against private firms for the contract. This has led to a client relationship between public operators and public authorities, or contracts with private operators.

In Europe, as in the United States, the contracts specifically for BRT services (or Bus with High Level of Service—BHLS) are very similar to conventional bus contracts, albeit with somewhat stricter performance parameters. The level of subsidy as well as the cost recovery ratio has little bearing on the degree of privatization in the BRT systems in higher-income economies. Fare-recovery ratios in both the United States and Europe range from as low as 20 percent in some cities in Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, and Eastern Europe, between 30 and 40 percent in France and much of Central Europe, to as high as 60 to 70 percent for German cities and on the New York City subway system.