5.1Demand Analysis for Corridor Selection

Without mathematics, there’s nothing you can do. Everything around you is mathematics. Everything around you is numbers.Shakuntala Devi, writer known as the “human calculator,” 1929–2013

The most important factor in determining whether a corridor is appropriate for BRT investments is the existing level of public transport demand. This is because the existing customers using a particular corridor are more than likely going to benefit from new BRT investments. A BRT built on a corridor with more existing transit customers is likely to have more beneficiaries than a BRT built on a corridor with fewer existing customers.

The methods for determining the existing level of transit ridership on a corridor are reviewed at length in Chapter 4: Demand Analysis. For the corridor selection process, the methodologies identified in Section 4.4 under “Basic Methodologies for Demand Analysis” offer a sufficient level of detail to make a simple determination of which corridors would benefit most from BRT.

Some planners have attempted to determine a minimum level of existing demand below which dedicating a lane exclusively to buses is difficult to justify. The Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (TCQSM), a guide generally used in the United States, recommends that a minimum ridership of 1,200 passengers per direction at the peak hour (ppdph) be a minimum threshold for an exclusive bus lane, as this is a reasonable average estimate for the number of customers that are generally able to use the lane when operating in mixed traffic conditions. In developing countries with much higher levels of transit ridership, it is likely that a higher minimum threshold would be set.

This guide does not mandate a minimum threshold of 1,200 existing bus or minibus pphpd, recognizing that there could be significant latent demand for high-speed transit in highly congested corridors or corridors with high rates of land development along them. The guide does recommend, however, that whatever the existing demand, at least a thousand pphpd should be attainable within the first year of BRT operations. Indeed, The BRT Standard (2014) deducts maximum points for systems that do not reach this. It should be possible to estimate demand for BRT during the first year of operation through a combination of existing bus or minibus demand, and some indication that there is likely to be new land development in the corridor, that congestion is likely to worsen significantly in the medium term, or that high existing bus, minibus, or rail demand in nearby corridors would shift due to overall travel time improvements.

Other planners have claimed that BRT as a technology cannot handle more than thirty-five thousand ppphd, so if a corridor has a projected number of customers greater than this then it should be reserved for heavy rail metro investments. Again, this guide does not make a specific recommendation of this type. Under certain conditions, BRT systems are able to carry more than thirty-five thousand pphpd even with only two lanes of exclusive bus lanes per direction. For example, TransBrasil is scheduled to open by the end of 2018 in Rio de Janeiro. This corridor is expected to carry up to sixty thousand customers during peak hour, due to extensive use of express services, two lanes per direction, and larger buses, such as articulated and biarticulated buses.

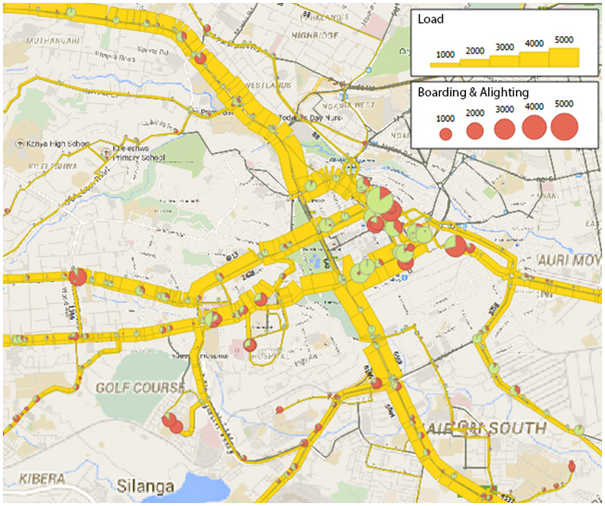

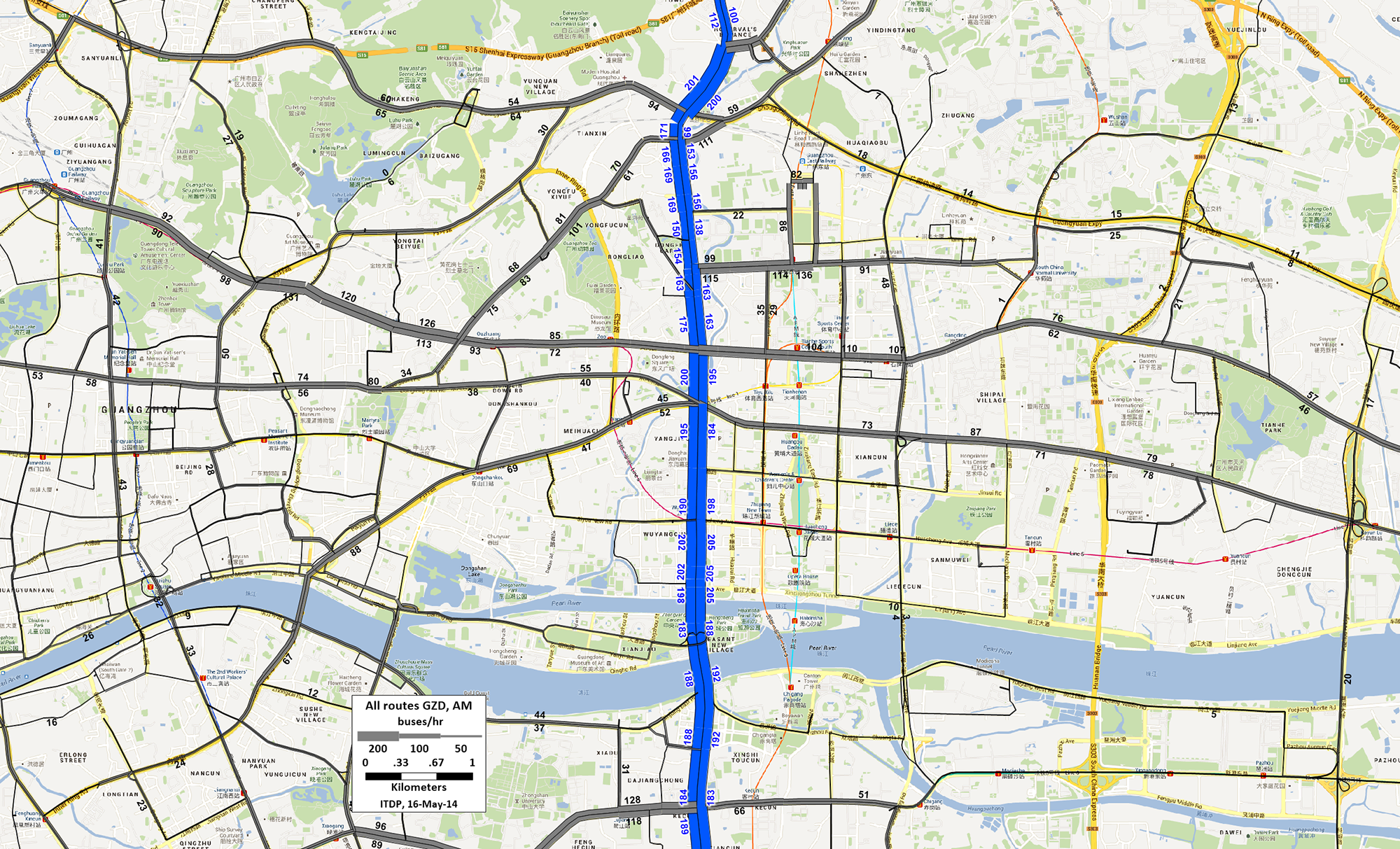

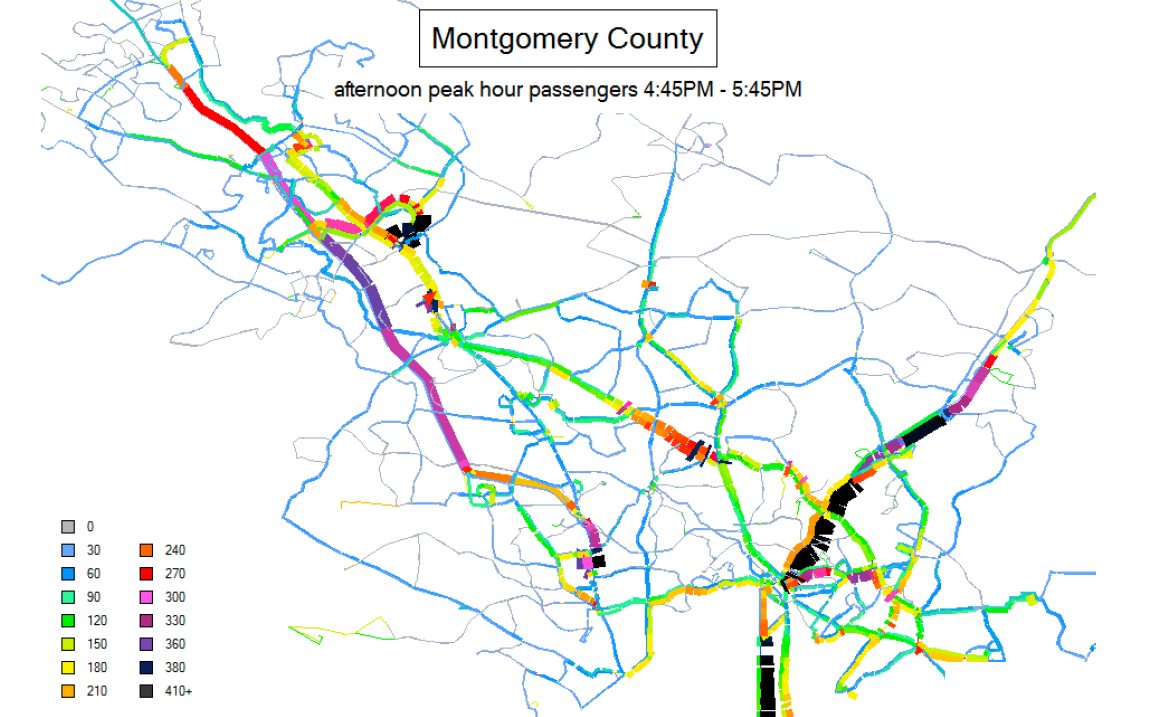

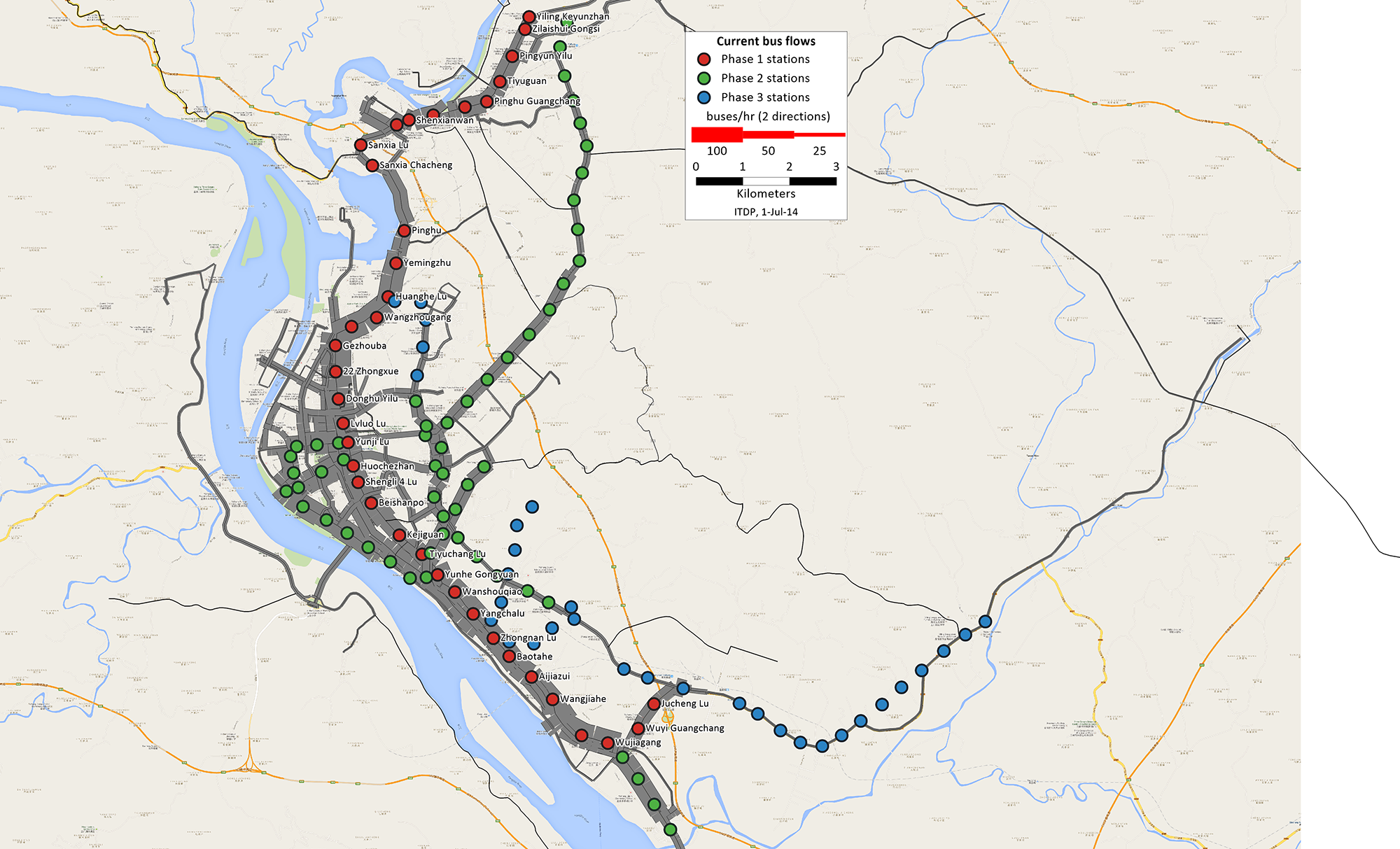

This guide recommends that the existing transit ridership data be presented to stakeholders in transparent form, ideally on a map with link by link loads.