5.5Framework for Comparing Corridors

The only relevant test of the validity of a hypothesis is comparison of prediction with experience.Milton Friedman, economist, 1912–2006

Making a good decision in a timely manner is not always facilitated by elaborate analysis. Often detailed economic, financial, social, and environmental impact analyses are too cumbersome and expensive to do. Picking the right corridor is as much a matter of common sense as extensive research. However, the data and mapping suggested above are reasonable analyses to perform at the corridor-selection stage, and should be sufficient to result in a set of corridors that make sense from a technical perspective.

Once a set of corridors has been selected on technical grounds, it is important that these create a BRT network. Otherwise, the corridor-selection process may still be open to political interference, and a corridor could be selected with no real technical basis. However, it may not be possible to build out every one of the selected corridors, nor must the corridors be implemented in the same order in which they were prioritized. Some additional work may be needed in order to account for factors that are more political in nature, as well as to build a more detailed cost-benefit analysis weighing one corridor against another. In this way, the selected corridors may be narrowed down to a smaller set and/or reprioritized into a network and phasing plan.

5.5.1Corridor Right–of-Way and Lane Uses

There is rarely anything innate about the characteristics of a corridor that would make it impossible to build BRT. Successful BRTs have been built on corridors as wide as Nueve de Julio Avenue in Buenos Aires—which is allegedly the widest street in the world—and as narrow as the historic downtown of Quito, which, at times, is only three meters across. Almost any road that can accommodate a bus can accommodate BRT in some form. Nevertheless, one-way streets, narrow rights-of-way, and suburban land use patterns all present special challenges for BRT system design.

A visual corridor review should look primarily at the existing configuration of the road, the basic traffic mix, the available right-of-way, and the land uses along it. One can get a general sense of the corridor now with tools such as Google Earth and Google Street View, but there is no substitute for walking the corridor. If survey data is not available, a laser distance measurer or measuring wheel can be used to record the road right-of-way width throughout each potential corridor.

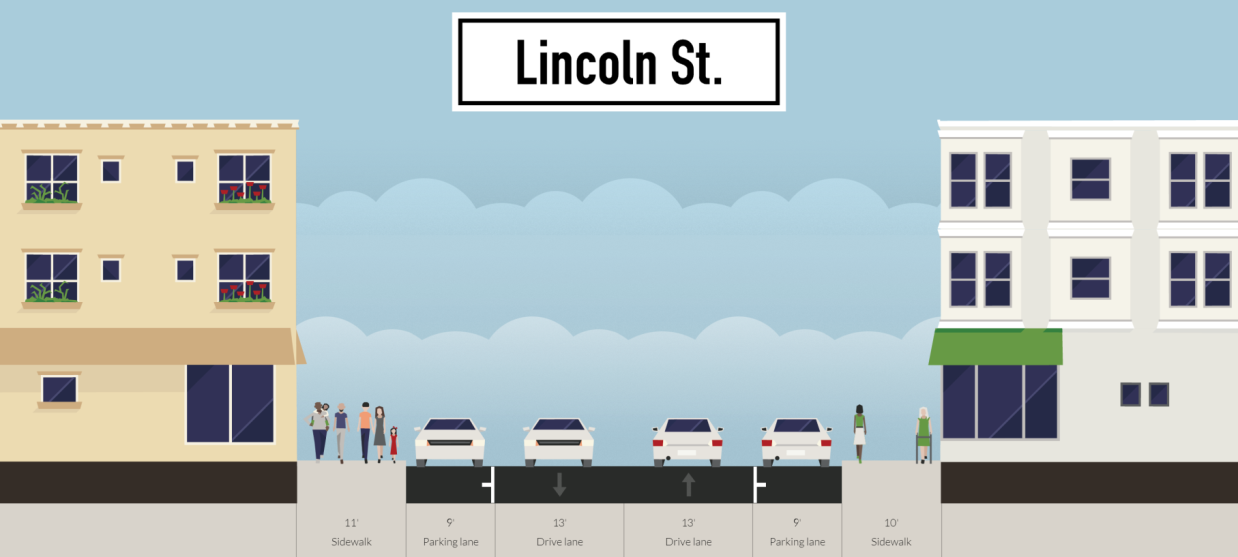

There are a variety of ways of presenting this information to stakeholders. Software programs such as Streetmix allow users to display road cross sections and replicate lane widths and rights-of-way on actual streets. Figure 5.20 shows a specific cross section using this software at a specific location along a proposed BRT corridor in Boston.

The roadway width can also be graphically shown along the length of the corridor using a plot of width against corridor location.

In addition to noting physical dimensions along a roadway, an initial survey should also note other features, such as the configuration and condition of medians and the presence of trees, utility poles, public art, or other features that may be expensive or politically difficult to relocate. Are the pedestrian paths adequate for providing access to a public transport system, or do they likely require widening? Are there difficult intersections along the corridor, such as roundabouts with fountains or artwork, or cloverleaf highway-grade interchanges, or narrow flyovers and bridges? Are there locations with low-cost land uses, such as surface parking lots, that could be procured for station stops where the road may need to be widened? A BRT engineer will tend to look for things on a visual survey of the corridor to get a general sense of how expensive it is likely to be to build a good-quality BRT along it.

While there is no clear metric for prioritizing corridors based on right-of-way, lane uses, or other features, this information should be included in the BRT corridor-prioritization analysis and presented to the public in a transparent way. Generally, if the public and/or the government supports a proposed corridor despite narrow right-of-way or other related issues, it should be kept on the list.

5.5.2Corridor Typology and Suitability for BRT

We define here five corridor types on which BRT projects are often considered. Generally, BRT only makes sense on the first three (Types I, II, and III) and is not recommended for the last two (Types IV and V). While some BRT elements could make sense for the latter types, this guide focuses only on true BRT systems, and so BRT is recommended only on Types I, II, and III.

- Type I: Urban Corridor. Urban corridors are typically arterials and secondary streets in dense urban environments with curbside activity, relatively short block lengths, and preexisting bus routes. Euclid Avenue outside of downtown Cleveland is an example of an urban arterial with a Silver Standard BRT. Other urban arterials include the Gold Standard BRT in Yichang, China completed in 2015; Geary Street in San Francisco, where a Silver Standard BRT is being planned; and many others. Most cities have at least a few urban arterial streets, and those streets are, by definition, well integrated into the urban context;

- Type II: Downtown Corridor. Downtown corridors are typically streets that go right through a city’s downtown. Downtowns are still the center of activity in most cities. As cities look to re-urbanize and revitalize their downtown cores, public transport directly through the downtown is critical. Often, downtown streets are narrow and congested, with very high levels of curbside activity. Sometimes there are preexisting bus routes through downtown streets, and other times, bus routes stop on the edge of a city’s downtown due to businesses and other powerful interests that fight to keep them out. Yet if there is any place where BRT could be successful, it is directly through a city’s downtown. Mexico City, Mexico; Bogotá, Colombia; Johannesburg, South Africa; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and many other cities have built Silver and Gold Standard BRTs on very narrow downtown streets, providing a large boost to BRT ridership and revitalizing many dying central cities.

Because Type I corridors are the simplest to verify in terms of ridership, and Type II corridors, while sometimes less simple to verify, are often likely to have the highest ridership of any corridor in a city, Type I and II corridors should be prioritized in the corridor selection process;

- Type III: Former Freight Rail Right-of-Way Corridor. There are many corridors that were once dedicated for freight rail but which at some point were abandoned. These corridors often make attractive corridors for BRT, since they do not require reallocating road space. Both Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, and Los Angeles have built Bronze Standard BRTs on former freight rail right-of-way corridors. Yet former freight rail corridors do not often have preexisting bus services already operating on them, nor are they generally well integrated into the urban environment.

Type III corridors have potential, in some cases, to be successful BRT corridors. However, because ridership is less assured than with Types I and II and because they do not generally integrate as well into the urban environment, Type I and II corridors should be prioritized over Type II corridors.

- Type IV: Suburban Arterial Corridor. Many streets just outside of urban areas classify as suburban arterials. Suburban arterials are often higher speed, carry higher capacities than urban arterials, and have less curbside activity (parking, deliveries, etc.). This is because suburban arterials tend to be lined by surface parking lots and most deliveries and passenger drop-offs occur from these off-road parking lots. There are also generally lower pedestrian-crossing volumes at intersections to impede right turning movements. As a result, there is little curbside activity, so dedicating the busway to the center of the road is not particularly needed. Hence, other than traffic congestion, the type of bus delay that BRT is designed to reduce does not typically exist on suburban arterials. Additionally, the distributed nature of trip patterns in suburban contexts means that bus boarding and alighting volumes at stops along suburban arterials are typically low, so off-board fare collection has less utility. Therefore, while some bus treatments could make sense on a suburban arterial (e.g., signal priority, curbside bus lanes, etc.), BRT rarely does. BRT on suburban arterial corridors is generally not recommended.

However, there is one condition in which BRT might be considered on a suburban arterial: If there is a concerted effort by the government to urbanize a suburban arterial, and thus transform it into a Type I “Urban Arterial Corridor,” BRT could make sense, provided the application meets the minimum pphpd requirements. In order for a city to demonstrate that a project is on an urbanizing suburban arterial, there must already be zoning changes in place that allow for a more urban form and the corridor must pass through at least one or two pockets of somewhat more urban character. Rockville Pike in Montgomery County, Maryland, USA, falls into this category. The proposed BRT project makes sense in light of the fact that the county has rezoned along Rockville Pike and has special zoning rules around high-capacity public transport stations. Further, and of particular importance, is the fact that the corridor connects to downtown Bethesda and downtown Rockville, both areas of a somewhat urban character. An urbanizing suburban corridor should at least connect to the more urban subcenters.

- Type V: Highway Corridor. Highways are often congested and in some cases, carry large volumes of bus customers. However, as on suburban arterials, the delay that BRT is designed to reduce does not typically exist on highways. And, unlike with suburban arterials, there is no possibility that a highway corridor will urbanize. A highway with transit needs is best served by express buses, operating in an HOV lane, which exit the highway to make stops. This is not BRT. Thus, if a Type V corridor has made it onto the list of possible corridors, it should be removed.