4.2Data Collection

The price of light is less than the cost of darkness.Arthur Nielsen, market researcher, founder of ACNielsen, 1897–1980

People travel from an origin address to a destination address, and may take one or more public transport services to get there; some walking and waiting will be required to complete the journey. The existing public transport services will be a good indication of where and how people travel. Therefore, analyzing existing public transport services and the conditions in which they operate is the first step in demand assessment.

A new BRT system is likely to change the combination of services that travellers will use. To understand how this will affect travellers, and whether or not this would be advantageous to them, it will be necessary to learn more about the pattern of trips, the origins, the destinations, and the volumes involved. This will require additional surveys capable of quantifying these patterns and enabling the construction of an origin-destination trip matrix for the study area. This information, combined with data about bus speeds in the network, will help in the design of a better BRT system.

Moreover, many travellers in a city have a level of choice about which transport mode to use, be it taxi (shared or otherwise), motorcycle, or car. Many of the environmental and economic benefits of a BRT system materialize if some of these users are attracted to BRT instead. The rate of attraction of BRT will depend on how good the routes are, and this will vary for different origin-destination pairs. If attracting car and motorcycle users is a key objective of BRT, then a more comprehensive transport model will be needed.

The next subsections discuss the minimum set of data that need to be collected to generate a reasonable estimate of demand for a proposed BRT system. These consist of:

- The routes of current public transport services; these can be mapped in GIS, transport modeling software, or Google Earth or Google Maps;

- The number of customers using key corridors by means of bus-route-frequency counts and visual-occupancy surveys;

- Bus frequency, preferably for every public transport route in the city, by direction, and in morning and evening peak periods;

- Bus speeds for each road section covered by a potential BRT route;

- Speeds of other vehicles on the existing road network;

- Boarding and alighting surveys (and supplementary spot counts at bus stops), to get a first impression of demand patterns.

In order to develop an improved public transport model it will be necessary to collect additional information; this is discussed in Section 4.5. For a formal, comprehensive transport model even more data will be needed, as discussed in Section 4.6.

4.2.1Route Maps

The first step is to simply map, or test the accuracy of any existing maps, of the current route structure of bus and minibus services. While in developed countries existing bus route maps are increasingly available in one form or another, it is surprising how difficult it often is, particularly in developing cities, to get even a basic up-to-date bus map. Mapping the existing public transport routes provides the first indication of routes with significant customer demand. While the roads that carry the most bus or minibus routes do not always correspond to the highest number of public transport customers on a given corridor, usually there is a strong correlation. If public transport routes are fairly well regulated, then municipal officials should already possess detailed route-itinerary information through registration records and maps of existing routes, but these records are almost always not fully reliable. In many developing-nation cities, the majority of public transport customers may be served by minibus operations that are weakly regulated. In such cases, there may not even be official records of specific routes. In other cases, registered routes and fleets may bear little resemblance to the actual situation.

A growing number of cities, particularly in the developed world, are putting their bus routes and schedules into GTFS or “General Transit Feed Specification.” Originally called “Google Transit Feed Specification,” this is a standard data format that a growing number of US public transport authorities are using to map and publish their current bus routes and bus schedules. So GTFS data is also usable as a map of the existing scheduled bus routes. Often the data entry is imperfect, so the accuracy of the routes has to be checked carefully. Other cities or public transport authorities may have already coded their existing bus routes into Geographic Information System (GIS) software or a travel demand model software.

Where neither of these data sources is available, it is best to simply ride all of the public transport routes using a simple Global Positioning System (GPS) device to record the geographic coordinates of all official bus stops and popular informal stops. Virtually all smartphones nowadays come with GPS and can be used as trackers, and a simple tracking device—with no screen, but capable of registering one day of movement each 10 seconds)—costs less than US$10. Apps for smartphones allow data, like bus stop information, to be entered immediately and tagged to the map. The issue with using these in the field will be the short battery life of phones compared to the batteries of strictly GPS devices. But with a GPS, more data cleanup will be necessary, such as labelling the bus stops.

The work can also be done without GPS devices, with printed estimated-route maps distributed to survey personnel, who will document bus stops along the route and make corrections to paper maps. GPS-based surveys will produce speed information as long as a travel log is associated with the survey, while performing a survey with paper maps will require that travel times be written down.

Depending on the data that is already available, itinerary surveys can be quite a big job in large cities, as they require developing a naming/coding system for the bus stops, identifying all of the routes, mapping the routes, preparing and processing survey data, and accounting for route variations. In a surprising number of cities this will be the only accurate public transport map in the city. Google Earth’s “.kml” format is an excellent way to store bus route map data, and the satellite imagery provides great assistance in mapping routes.

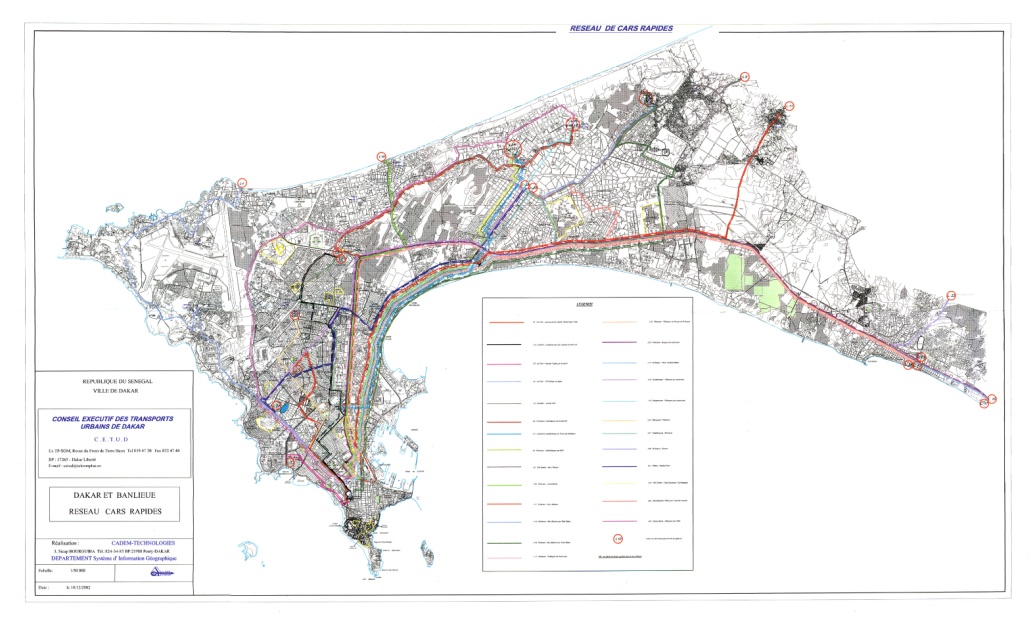

The map in Figure 4.1 is one of the first efforts to map the existing minibus Car Rapide and Ndiaga Ndiaye in Dakar, Senegal. This activity is often a critical first step toward bringing such services into a transparent regulatory framework.

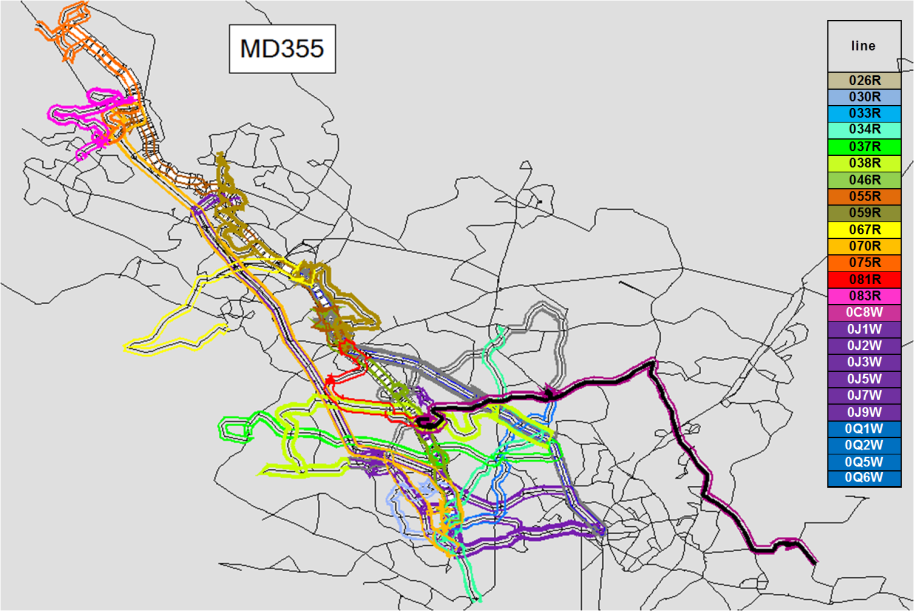

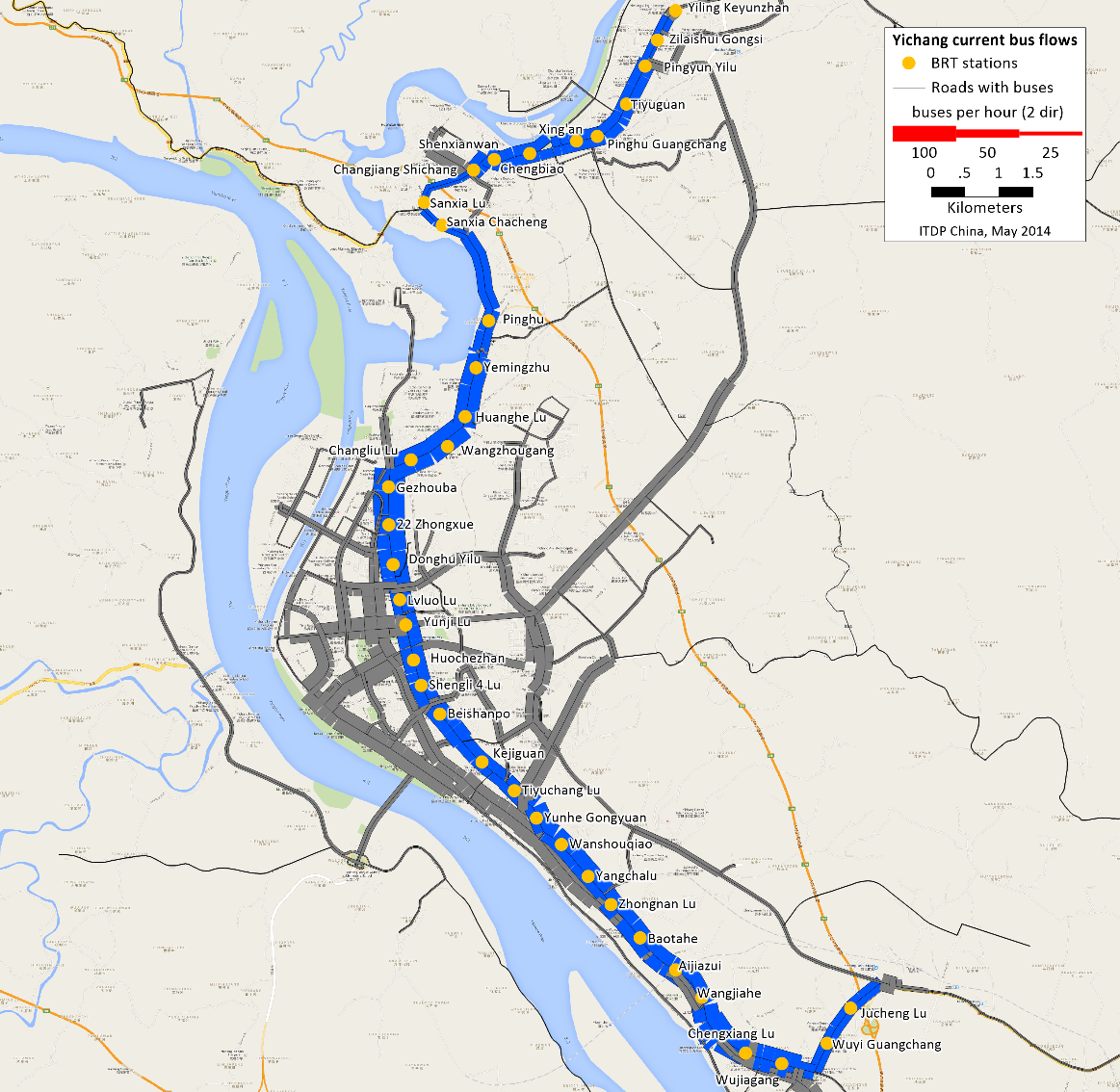

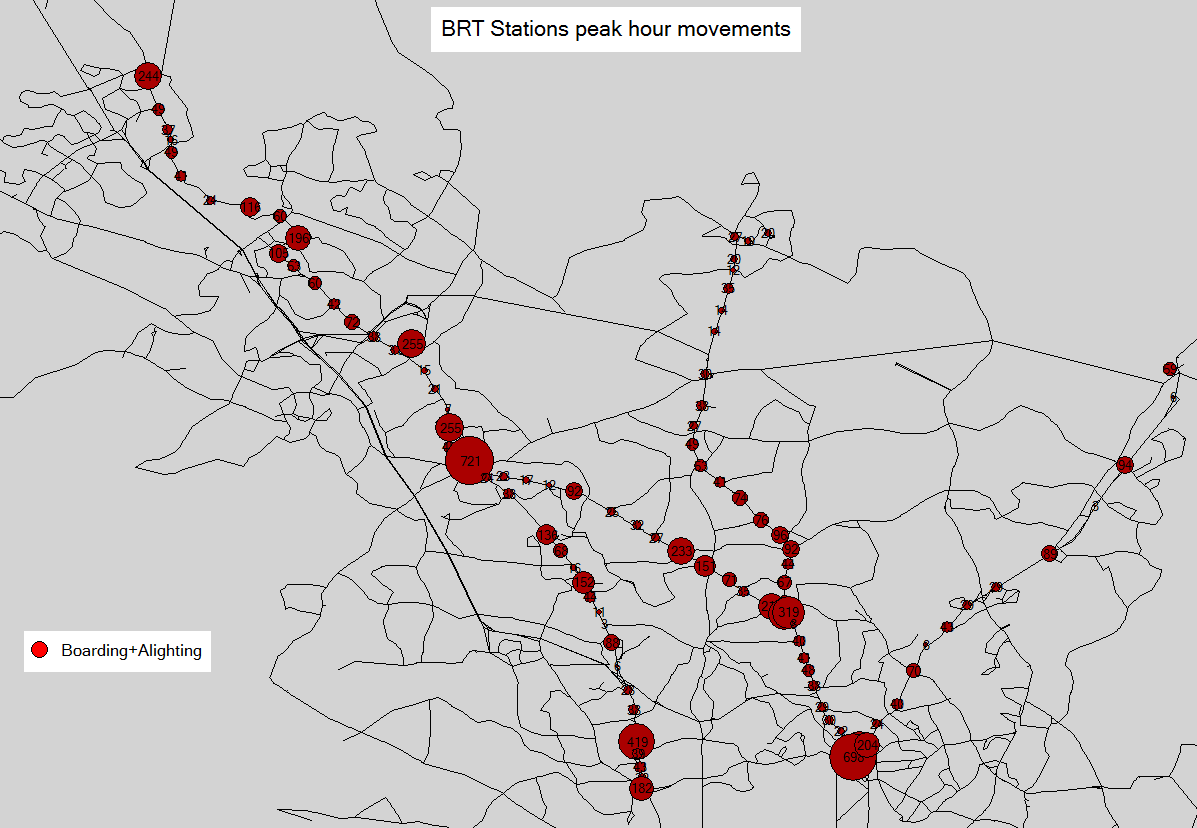

Once the coordinates of the bus and minibus routes have been collected and mapped, these itineraries can then be input into GIS and/or transportation modeling programs, with supplementary input from associated spreadsheet or database files; see, for example, Figures 4.2 and 4.3.

With just this amount of information, the main potential BRT corridors should already be obvious in most cities: the corridors where many bus and minibus routes converge.

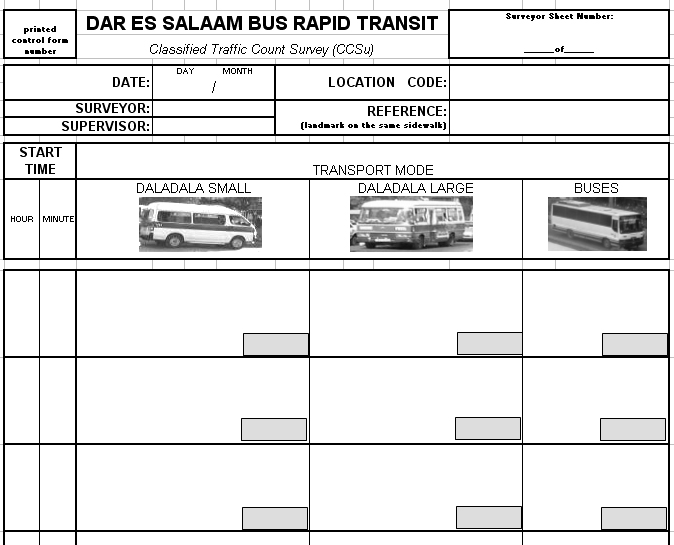

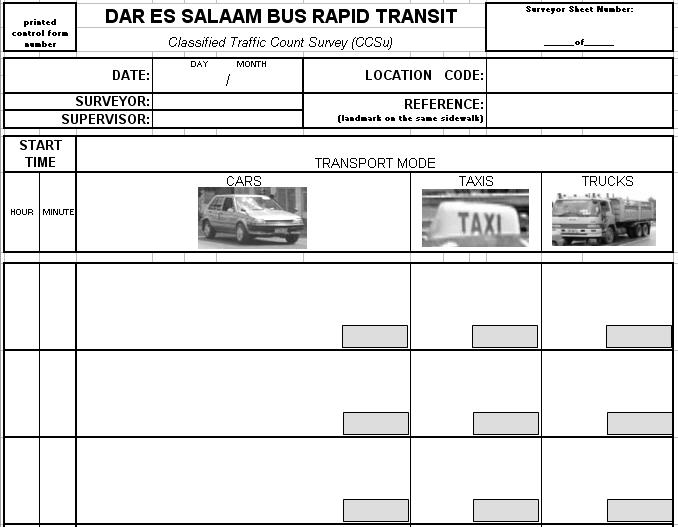

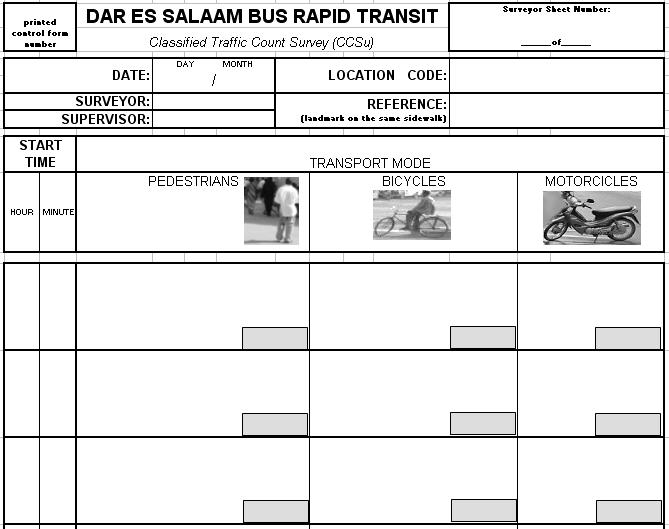

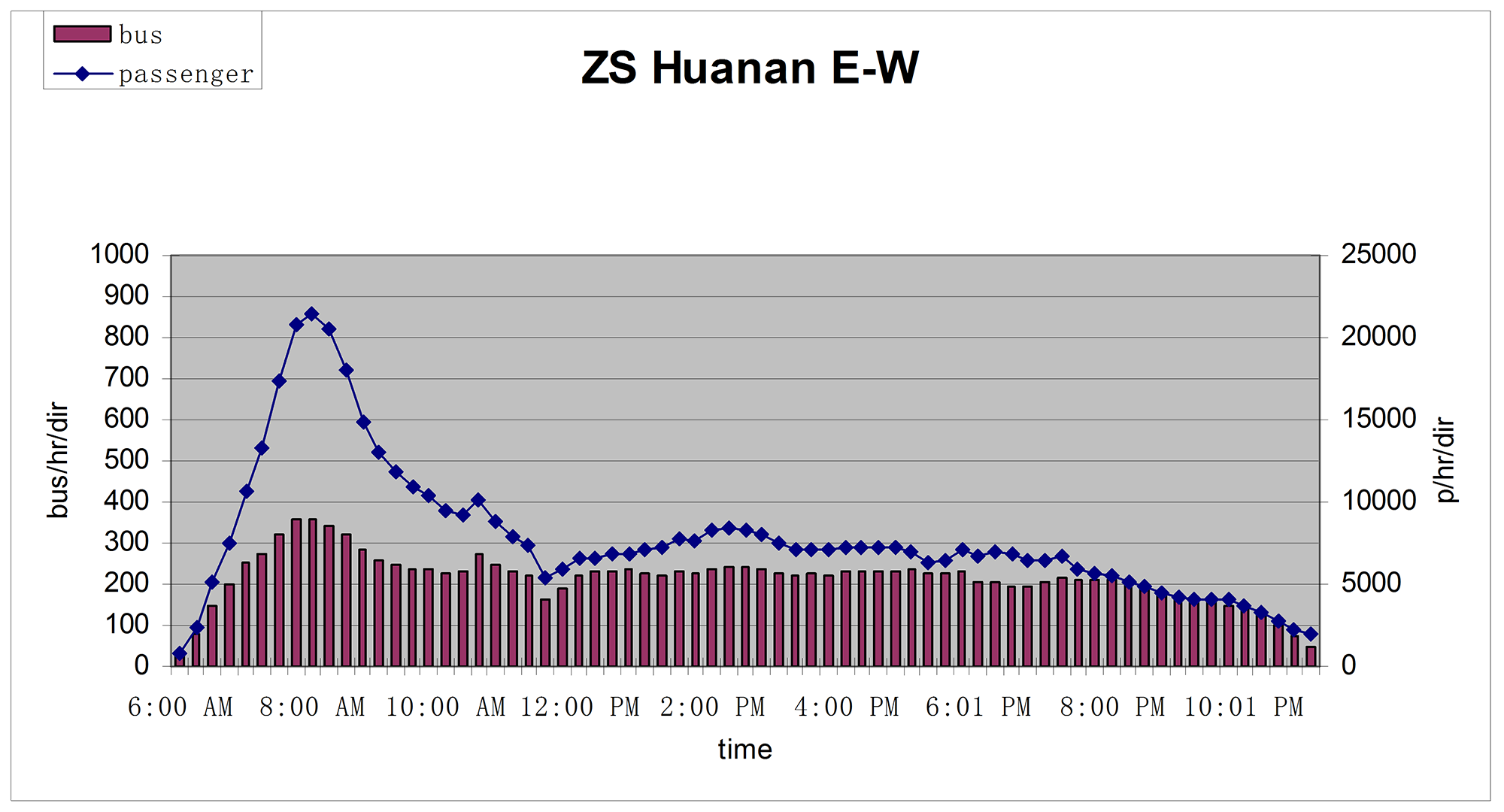

4.2.2Vehicle and Customer Counts

With the basic public transport route structure in hand, bus and minibus counts are the next step in translating bus-route frequency and occupancy numbers into rough public transport demand estimates. These counts can be used to calibrate an existing traffic model, to understand the public transport demand across the city, or to plan services along an already-identified corridor. The first step is to have a reasonable understanding of demand across the network, and then to focus on a particular corridor. The number of buses (or other types of public transport vehicles) per route, combined with their estimated occupancy rates (discussed in the next section), will already yield a crude estimation of a corridor’s existing demand (Figures 4.4 and 4.5).

The strategic selection of the points to conduct the traffic and occupancy survey will determine the extent to which the survey results will represent the actual situation. Determining where to do traffic counts can be more of an art than a science, but some general rules can be applied. Generally, the survey locations should allow most trips to be easily captured with a minimum of resources and effort.

When designing a BRT system we are looking for the highest potential public transport demand routes; traffic counts should be conducted in locations where public transport demand may be high. Using the map of existing bus and minibus routes, counts should be done on arterials where many routes converge. Arterials where local knowledge or simple observation indicates high volumes of buses should be counted as well. If a city has a fairly clearly defined central business district (CBD), and most of the trips start or end in the CBD, then it is sometimes possible to do traffic counts at the entry points along a “cordon” around the CBD. For example, in Dar es Salaam, the entire CBD can only be entered through five major arterials and by ferryboat, and few trips both originate and end within the CBD. By conducting traffic counts at just these six entry points, it was possible to obtain precise CBD demand data for each major arterial as well as the collective totals, and the frequency of nearly all bus routes in the city.

If travel into an area is fairly concentrated along a single direction, perhaps from north to south or from east to west, then the conditions may allow an even more selective application of counts. Cordon counts and screen line counts follow the same overall principle: while “cordon line” refers to a surrounding area, a “screen line” refers to the divide of an area into two sides (usually along a river or a train line) to learn the flow passing from one side to another.

Once it is determined that public transport ridership is concentrated along a few key corridors where there is potential to build BRT infrastructure, it is a good idea to do frequency and occupancy counts at several points along this prospective corridor, which also helps determine appropriate corridor length.

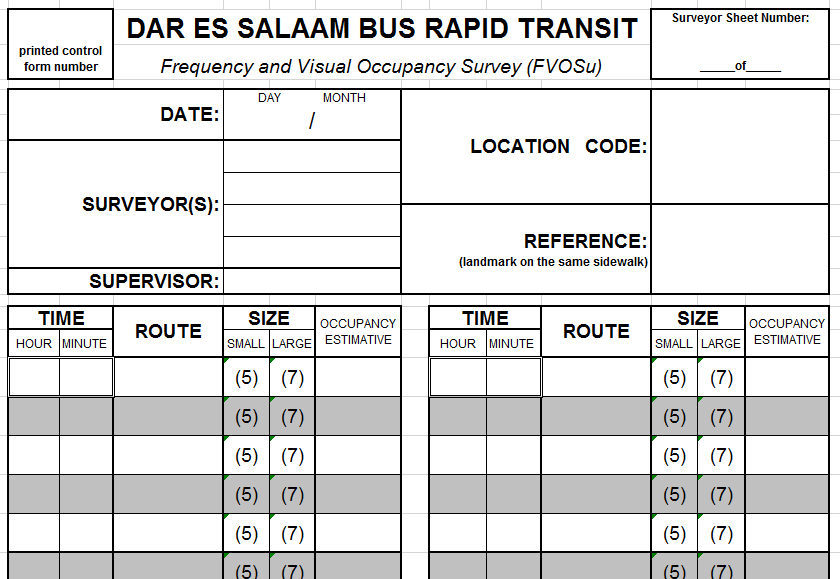

Ideally the frequency and occupancy counts should be done for each bus and minibus route. Even if the transportation department or the bus authority provides the bus route by bus-route frequency information and ridership information, it is always essential to do the counts anyway, because the data provided is rarely completely reliable.

Even if the project team does not plan to eventually use a traffic model, it is a good idea to do a number of counts at a larger selection of critical points all around the city, strategically chosen based on a rough estimate of those locations where most daily trips would pass. These counts will be important in calibrating the public transport model. The model will try to predict existing public transport ridership in each corridor, but it may make inaccurate predictions and need to be adjusted; the counts are needed to determine if the model is an accurate reflection of reality.

One does not need to count so many sites that it becomes cost-prohibitive. For example, in the city of Dar es Salaam (population of approximately 2.5 million inhabitants at the time, nowadays more than 4.3 million) traffic counts in about thirty locations captured a large majority of the trips, and in Jakarta (metropolitan population of above 25 million inhabitants) bidirectional counts in about 100 locations were sufficient.

Often, when one is doing counts of public transport vehicles, one also does counts for the rest of the traffic. Later, these counts will be useful in calibrating more complex demand models, developing rough estimates of impacts on level of service, and other uses. (See Figures 4.5, 4.6, 4.7, and 4.8.)

This information will also provide an important first clue as to how many customers might switch from private cars or motorcycles to public transport as a result of the new BRT system. Such data will be important to estimating projected greenhouse gas emission impacts, which may be critical to eligibility for Global Environmental Facility (GEF) funding.

Additionally, if a full transport-demand model is later used, then the existing data will be in a form that is readily adaptable to a more inclusive analytic package.

As the complexity of the counting process increases, though, the resources required to obtain an accurate count also increase (Figure 4.9). To identify all vehicles and produce a valid count across multiple traffic lanes, a counting strategy becomes vital. One option is to employ counting teams that involve many people at a single location in order to properly record all vehicle types in each of the lanes. Alternatively, video technology can be utilized to record traffic movement and to allow a more precise count at a later time. The video record allows quality-control sampling to ensure that the counting team is performing at a reasonable level of accuracy. With all counting strategies, survey personnel should be properly trained so that all participants have a common understanding of the task at hand.

4.2.3Occupancy Surveys

The number of vehicles is only one part of the demand equation. Knowing the average number of customers in each of the vehicle types at any given time period provides the other half of the demand input data. Given the diversity of possible vehicle sizes, the occupancy data should be categorized and collected by vehicle type. The survey should thus identify vehicles according to their seating numbers or maximum-capacity numbers. For public transport and minibus vehicles, some of the possible categorizations could include:

- Seventy-seat bus;

- Thirty-five-seat bus;

- Sixteen-seat minibus (Figure 4.10);

- Seven-seat van/large rickshaw;

- Three-seat auto rickshaw;

- Shared taxi.

Ideally, the data on the number of vehicles and the occupancy levels should be collected simultaneously. Usually surveyors record the vehicle type, the number of customers (traditionally a percentage of possible occupancy set at multiples of ten or twenty-five is used, but there is no disadvantage in estimating the exact figure), the route number (if visually evident), and the time of observation. The occupancy provides the basis for a fine estimate of corridor demand. Recording the time is necessary to identify peak and non-peak periods, which should be identified at a resolution of ten-minute intervals. Such a resolution does not disrupt the survey and is enough to identify peak moments, even for a specific route; lower resolutions (five minutes) are not practical and are not of much use, unless we are interested in fluctuations due to traffic-light cycles. Peak and peak of peak period figures are needed for dimensioning the system, especially station capacity (see Chapter 25 for more on station planning).

It is important to have a notation convention for surveyors to enter when they cannot identify the route number (which should be different from “I saw no visible identification”) and to enter when they cannot estimate the occupancy (which is different from “no-occupancy,” which would be zero customers). It is also preferable for a surveyor to pause (and record the pause) due to a distraction rather than trying to keep a poor record while dealing with it. A sampled occupancy survey is better than a bad occupancy survey. Figure 4.11 shows how much more information occupancy surveys reveal in comparison to frequency-only surveys.

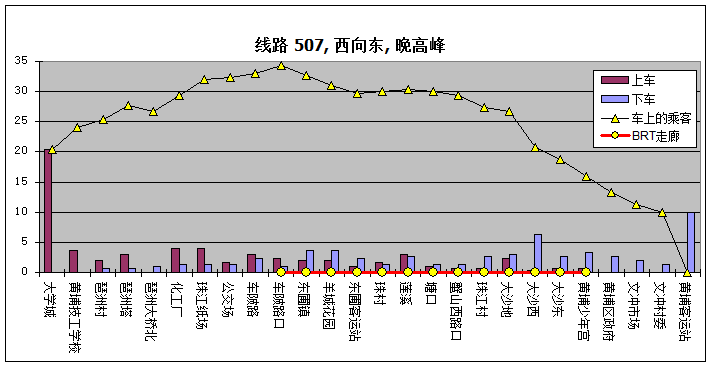

4.2.4Boarding and Alighting Surveys

Once the corridors with the highest levels of public transport demand have been identified through the route mapping and vehicle and occupancy counts, an additional boarding and alighting survey on selected public transport and minibus lines can be conducted (Figure 4.13) to further understand travelling patterns. This same data set will also show how many customers are on the bus at any given time.

Boarding and alight surveys can be conducted in two main fashions:

- Surveys of all routes in one station (surveyor is at the station): one of the most important pieces of information when sizing a BRT station is how many customers will be boarding and alighting at each station, and the best way to estimate this is to see how many customers are currently boarding and alighting buses and minibuses in nearby locations.

Surveys of all stations of one route (surveyor is on the bus): in this type of survey, surveyors should ride the entire length of each major public transport route during rush hour and record how many people get on and off the bus at each stop. Once this is done for all the routes on a prospective BRT corridor, the boarding and alighting numbers and onboard bus numbers can be consolidated to determine the existing ridership for each stop and each link (bus stop to bus stop). Many good BRT systems have been designed with no more information than this same data set, which will also show how many customers are on the bus at any given time. Additionally this arrangement can:

- Survey the network speeds (bus stop to bus stop) and the average speed (discussed below);

- Relate every customer’s boarding and alighting stops, by handing numbered cards to customers at the moment of boarding and retrieving them when the customer exits the bus. At each stop the number of the last card handed to customers boarding the bus is written and the cards returned from alighting customers are placed in an envelope used only for that station (this has also been done with surveyors handing bar-coded cards and carrying bar-code readers attached to a raspberry pie with GPS hanging on their belts).

If a city is already using automated passenger counters (APC) or electronic ticket machine data, this data is sometimes useful for getting accurate boarding and alighting data. In the best cases, it can provide bus-stop-specific boarding and alighting numbers hour by hour, for every bus route in the system. Sometimes it is difficult to correlate to specific bus stops, but usually this can be allocated to the nearest bus stop without major loss of accuracy. In a growing number of cities, data from modern fare-collection systems can also be used to get boarding and alighting numbers per bus stop.

If neither of these technologies is in place, manual boarding and alighting surveys will need to be conducted. Since this survey is relatively time-consuming and expensive, it can be done for a subset of routes in the city; for example, those routes that have a frequency greater than three buses per hour and overlap for more than 10 percent of their length with the BRT corridor. Properly sampled, and in combination with previous survey data, it is possible to draw an internal picture of current public transport system use (i.e., correlated users’ entrance and exit points) in the influence area, in a way similar to that discussed in the next subsection.

4.2.5Methods of Developing an Internal Public Transport Origin-Destination Matrix

Recently, BRT system planners have been developing methods for creating an internal public transport origin and destination matrix (OD matrix) based on sampled boarding and alighting and ridership data. In a growing number of cities, ticketing systems collect information about where a specific ticket ID enters a system, but very few systems also collect data about where a specific ticket ID leaves the system. In the more typical case, ticket validation happens upon entering turnstiles, and it is possible to construct an OD matrix by locating the morning ticket-validation point as the trip origin (where the person first enters the system in the morning), and the afternoon ticket-validation point as the destination (where the person enters the system in the afternoon); intermediate validations may indicate transfers depending on analysis of the interval between validations. The main difficulty to this approach is that bus positioning systems and ticketing systems are independent and both generate huge logs, which require a lot of computational power to process (a few hours to process one day of data on a laptop). But this often generates a usable baseline OD matrix with a much larger number of data inputs than any survey method would ever gather. Currently, methods are being developed for doing this in faster ways.

While this, as well as the more detailed boarding and alighting survey, can generate a fairly accurate OD matrix of the boarding patterns in a bus system, it does not reveal the original starting point or eventual destination of customers whose trips involved more than one trip segment or mode, and may not provide a matrix to be directly assigned to the network. For example, if a customer surveyed travels from A to C via B, it will cover both the trips as A-B and B-C separately but will not predict a transfer at B. To determine this information, the onboard survey can be supplemented with an off-board interview survey at major transfer points that needs to be expanded using frequency and occupancy counts.