15.2Fare Parameters

Never let anyone define what you are capable of by using parameters that don’t apply to you.Chuck Close, artist, 1940–

The business structure of the BRT system should do what it can to ensure long-term high-quality service to its customers. BRT systems are vulnerable to being used for political purposes, other than providing high-quality service to their customers. A profitable system might see its resources reallocated to other purposes. Procurement decisions can be made for political rather than technical reasons. Even the exclusive use of the road right-of-way is vulnerable to being revoked by new political administrations. A good business structure backed by enforceable contracts can play a critical role in protecting good quality BRT service over the long term.

Because BRT usually aims to create a “market,” the business model for the BRT system as a whole must be developed, and this business case has to be built up from the business case of the separate components of the system: the trunk operations, feeder bus operations, fare systems, and possibly security services as well. The development of the system’s business model will require some initial analysis of projected operating costs and projected revenues. This analysis will help identify the conditions in which operating companies can reach profitable (and thus sustainable) revenue levels. The calculation of operating costs and projected revenues will also allow initial estimates of the fare levels that will allow the system to cover its operating costs.

One of the key purposes of the business plan for the system as a whole will be to estimate the overall profitability of the system. Knowing how profitable the planned BRT system will be in advance is a critical first step in defining which elements of the system can be financed in a sustainable manner from the fare box revenue, and which elements of the system need to be paid for by other investment.

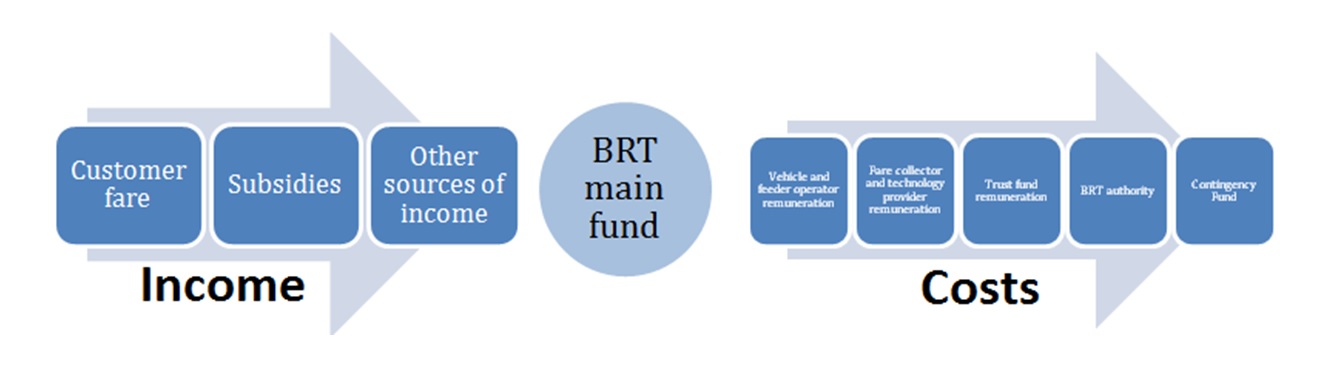

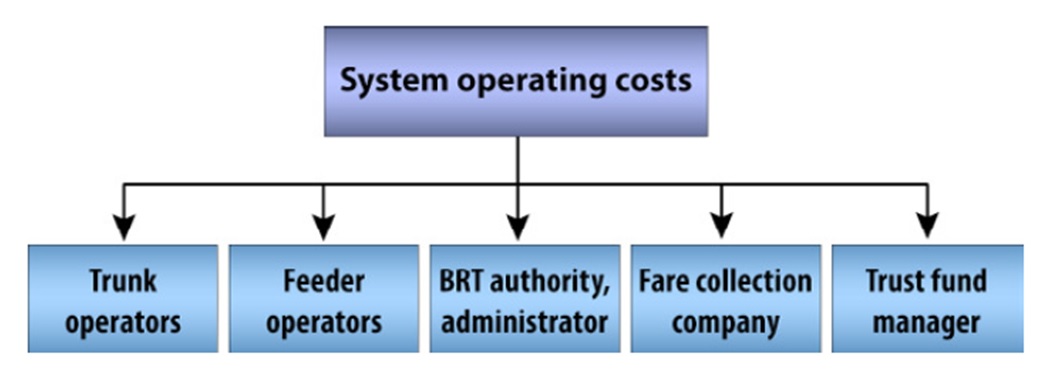

The operational costs of the BRT system as a whole are potentially composed of the following components:

- Payment to trunk operators;

- Payment to feeder operators;

- Payment to the BRT public authority;

- Payment to fare collection operator;

- Payments to trust fund manager;

- Credit reimbursements.

These components are illustrated in Figure 15.8.

15.2.1Trunk Operator Remuneration

From the point of view of the system as a whole, the cost of vehicle operations on the trunk lines depends on the contractually determined rate that the BRT authority has agreed to pay the vehicle operator per kilometer, multiplied by the projected total annual kilometers of operations that are programmed. This relationship is outlined by the following equation:

Eq. 15.2: Payment to trunk operators:

\[ \text{Pay}_\text{Trunk Operators} = \text{Distance}_\text{Daily} * \text{Fleet} * (\text{cost}_\text{Operating}+ ROI) \]

Where:

- \( \text{Pay}_\text{Trunk Operators}\): Total payments to trunk operators;

- \( \text{Distance}_\text{Daily}\): Projected needed daily vehicle kilometers;

- \( \text{Fleet}\): Projected total number of vehicles;

- \( \text{cost}_\text{Operating}\): Estimated operating cost per kilometer;

- \( ROI \): Return on investment.

15.2.2Feeder Operator Remuneration

Similarly, from the point of view of the feeder operators, the operational cost will simply be the amount that the BRT authority has contractually agreed to pay the feeder operators per kilometer (or per customer, whatever the contract stipulates), multiplied by the total projected customers or kilometers provided by the planning of the system.

Both for feeder and trunk operators, the revenue they receive should be enough to cover operational expenses plus the return on investment markup (Table 15.2).

Table 15.2Trunk and Feeder Services Cost Breakdown.

| Cost item | Trunk services | Feeder services |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel | 24.6% | 17.3% |

| Tires | 4.7% | 5.2% |

| Lubricants | 1.5% | 1.7% |

| Maintenance | 9.0% | 10.8% |

| Wages | 14.7% | 29.2% |

| Station services | 0.0% | 2.6% |

| Other fixed costs | 45.5% | 33.2% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Source: TransMilenio SA.

15.2.3Fare Collector Operator Remuneration

Payment to the fare collection company will similarly be determined by whatever payment was negotiated at the outset. In the Bogotá system, for example, a percentage of the fare collection is paid to the Fare Collector Operator. This operator may also provide additional services such as Fleet Management or Passenger Information Services, and must also be remunerated for them. For TransMilenio Phase III, the Fare Collector Operator is paid for the additional services based on a fixed amount for installed equipment both onboard and in-station.

15.2.4BRT Authority Remuneration

The administrative expenses of the BRT authority are principally the cost of salaries for the staff. Whether the operating costs of the BRT authority is paid from the fare revenues depends on how the business plan is initially organized. In some cases, the system administration may be simply part of the transport authority’s general budget. As with vehicles and other components, the viability of including administrative costs as part of the revenue distribution depends on the expected system profitability and the targeted customer fare level.

15.2.5Trust Fund Manager Remuneration

The trust fund manager is an independent entity that receives the revenues collected from the fare collection company. The trust fund manager is then responsible for distributing the revenues to each party based on the prior contractual agreements. In many cases, the trust fund manager is a bank or other trusted financial institution. The trust fund manager receives a fixed percentage of the total income of the system for providing these services. Figure 15.9 shows a summary of a BRT’s operational income sources and costs.