18.5Institutional Structure

Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights leader, 1929–1968

Institutional arrangements for the fare collection and verification system vary widely from system to system, with different benefits and risks. Most successful BRT systems have adopted a public-private partnership model to handle fare collection. These systems involve the following parties:

- The manager of the money (usually a bank or money manager);

- The equipment provider;

- The fare provider;

- The fare system operator;

- The public transport authority or its parent agency.

How these functions are related institutionally depends on the technical competence of the public transport authority or its parent agency, the level of concern about corruption, the type of system desired, and the need for financing it with private money.

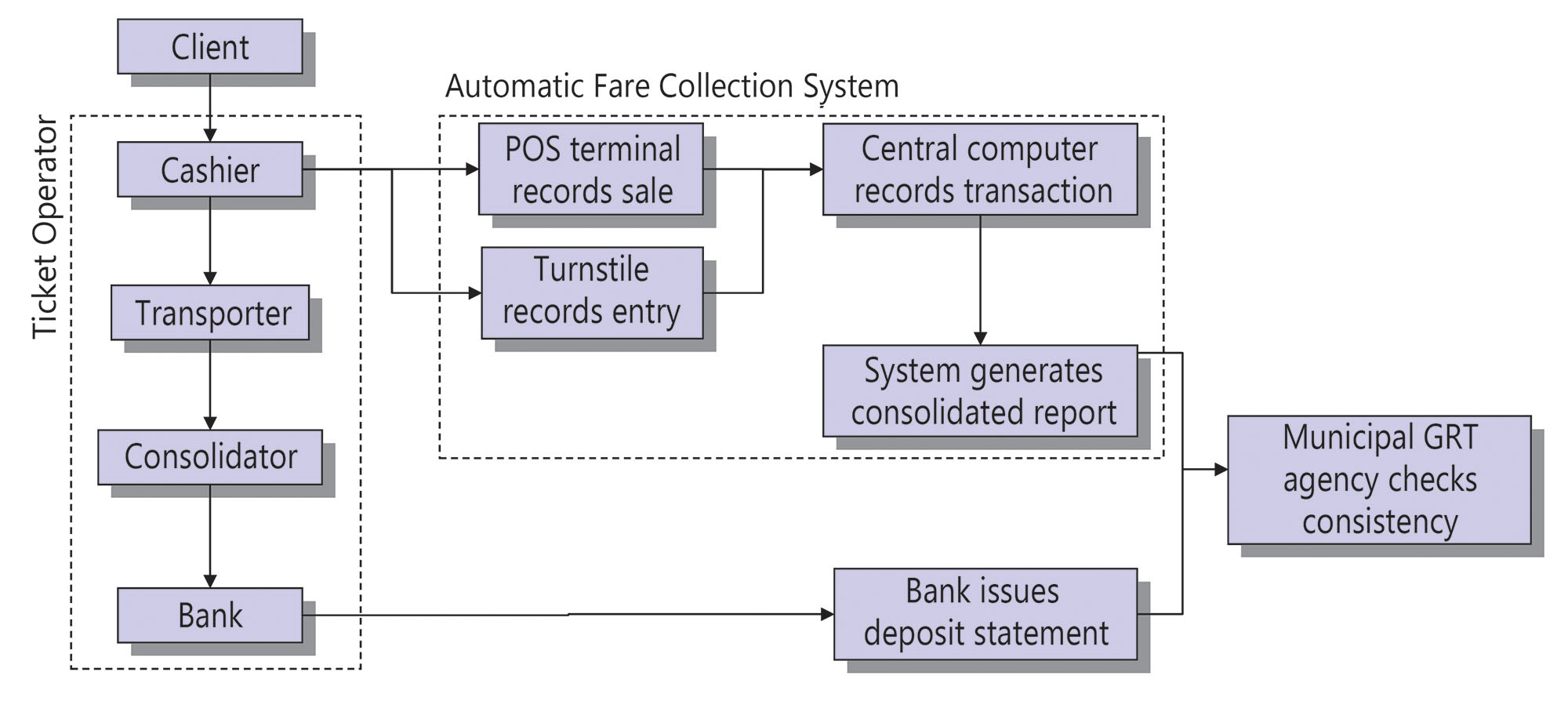

It is fairly standard for the manager of the money, the equipment provider, and the fare provider to be closely associated, while the fare system operator is separate. This allows the equipment provider/financial manager to monitor the fare system operator in order to avoid corruption. Figure 18.7 outlines a typical system structure.

In the case of TransJakarta, splitting the responsibility for operating the fare system and procuring the fare system equipment led to major problems. When problems with the equipment technology emerged, the fare-system operator was unable to fix them, and claimed to have no legal responsibility for fixing the problem. The fare system equipment supplier should have been liable, but the contract signed with TransJakarta did not provide for this eventuality. There was nothing inherently wrong with the structure, but any structure not backed by solid legal contracts outlining financial liability for service failures can lead to disaster.

In the case of TransMilenio in Bogotá, the fare system was implemented through a unique build-operate-transfer (BOT) model. In this case, there was a competitive tender for a single company to both procure the fare system equipment and operate the fare system. The company that won this tender, Angelcom SA, both selected and paid for the fare equipment and operates the system (Figure 18.8). The contract signed was between the public operating company (i.e., TransMilenio SA) and the private firm, not between the Department of Transport or the Department of Public Works and the private firm. The private company in turn receives a fixed percentage of the revenues from TransMilenio. A third company was contracted by TransMilenio to be responsible for managing the revenue once collected. All fare revenue in TransMilenio is placed by the operator into a trust fund, and this company manages the TransMilenio Trust Fund on behalf of all the parties with a vested interest in the fair and accurate division of this revenue: TransMilenio SA, the trunk line operators, the feeder bus operators, and the fare collection company.

This build-operate-transfer institutional model for the fare system had some advantages and disadvantages. The system was eventually able to attract private investment for the fare system equipment in a country where private investment was difficult to secure due to political risk. This private financing reduced the initial capital cost of the TransMilenio BRT system. However, the fare system operator receives 10 percent of TransMilenio’s total revenue, whereas its operating costs are probably much lower. As such, it puts an unnecessary financial burden on system operations. It would have been less costly if the fare system were simply purchased outright by TransMilenio.

This structure did assure that the fare system functioned on a basic level. Because Angelcom SA’s profits are determined by the success of the system, the company has a vested interest in making sure the system operates properly. Because it is also responsible for operating the system, the company has a vested interest in getting equipment that functioned properly. Because Angelcom SA was a fare system operating company, it also knew more about the appropriate technology than the government, and was able to negotiate better equipment contracts with subcontractors and receive lower prices. By privatizing the procurement contract, the risk of corruption in the procurement process is lessened.

On the other hand, Angelcom SA bought relatively cheap equipment in an attempt to save money. The company complied with its contractual obligations but the quality standards were reasonably poor, the design was inflexible and of poor quality, implementation was slow, and there were a host of technical problems in the first month of operation. These problems could have been solved within the current structure by imposing harsher penalties for poor performance, and by having TransMilenio specify in the tender a higher technical standard for the fare equipment. TransMilenio could even have handled the procurement independently and then awarded the contract to the winning fare system operator. In this way, the operating system bidder becomes the owner of the new equipment, and can be required to pay for the investment, but the government would retain tighter control over the equipment selection process.

It is fairly common in the public transport industry to separate initial equipment procurement from operations. This practice is usually done when there is a public transport authority that directly collects the fare-box revenue, and where there is no expectation that the operating company will invest in the system. Technology providers such as Ascom Monetel, ERG, INDRA, or Scheidt and Bachmann have focused their attention on the technology development and integration tasks, leaving the fare system operation to the public transport agencies. This structure can reduce the on-going financial burden that a BOT would impose. However, if equipment procurement and operations are separated, contracts will have to be structured carefully to ensure that the equipment providers are responsible to the operating company for system maintenance.