17.3Financing BRT Capital Costs

A promise made is a debt unpaid.Robert W. Service from the poem, “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” poet, 1874–1958

Whatever the ultimate source of funding for a BRT project, in many circumstances it is advisable to debt finance a BRT’s capital costs. BRT infrastructure, in particular, requires large, up-front capital investments, and many governments do not have the cash on hand to bring a minimum operable BRT link on line in a reasonable time frame. If the project is well designed, with an economic rate of return above the cost of capital, it is advisable to borrow any extra money needed to complete the BRT project as soon as possible. The sooner the minimum operable link is completed, the sooner the economic benefits can be enjoyed. With debt financing, much more can be built much faster, so the economic benefits can begin to accrue faster, yielding a greater overall benefit. Also, as the benefits will be enjoyed not only by today’s taxpayers but also by tomorrow’s taxpayers, it is reasonable to pass on some of the cost to the taxpayers of the future. As such, BRT infrastructure is a classic case for debt financing.

Additionally, the rigor of project evaluation often required by debt financing often helps ensure a better planned project. Lenders, as a third party, may have a stronger incentive to critically evaluate a project’s long-term prospects, as the loan is likely to still be due long after the politicians initiating the project have left office.

Building a BRT system is a major investment. As noted in Chapter 2: Why BRT, BRT systems will generally cost in the range of US$5 million per kilometer to US$20 million per kilometer. The actual cost will depend on a range of factors including the complexity of the infrastructure, the capacity level required, the desired quality of the stations, the road surfaces and terminals, the necessity for property acquisition, the need for flyovers or tunnels at rivers, railway crossings or problematic intersections, the amount of general infrastructure improvements included in the corridor reconstruction (sewage, drainage, and electrical improvements), and the level and quality of corresponding public space improvements in the corridor (landscaping, cycling and pedestrian facilities, street furniture, etc.). Since a Phase I project will generally involve anywhere from 10 to 50 kilometers of infrastructure, anywhere from US$50 million to US$1 billion may be required for a project’s initial phase. Many governments have a hard time mobilizing this level of resources in a single year or even in a few years.

Debt financing is also common for the procurement of the BRT vehicle fleet. Not all BRT systems require the procurement of new vehicles, but most of the better-rated BRT systems require the procurement of new vehicles compatible with special BRT infrastructure. The cost of BRT vehicles varies from as low as US$75,000 (for a standard 12-meter diesel vehicle in India) to US$750,000 or more for a bi-articulated vehicle, or articulated hybrid diesel-electric vehicle. Total vehicle procurement costs are thus likely to run into the tens of millions of dollars. The expected economic life of a BRT vehicle tends to be from about seven years (in the case of Indian or Chinese vehicles) to about ten to twelve years (European vehicle). Existing operators rarely have the up-front capital required to finance the entire fleet of new vehicles. Most BRT systems have therefore turned to debt financing for vehicle procurement.

17.3.1How Much to Debt Finance

All other things being equal, a well-designed BRT project, backed by reliable revenue sources and with a reasonable projected rate of return, should qualify for a debt to equity ratio of about 70:30 (Izaguirre, A. K. and Kulkarni, S. P., 2011). For example, if a total investment needed is US$100 million, only US$30 million would be needed in cash from the funder (general tax revenues over a year or two), while the other US$70 million can be financed by debt, and only repaid gradually, usually also from tax revenues.

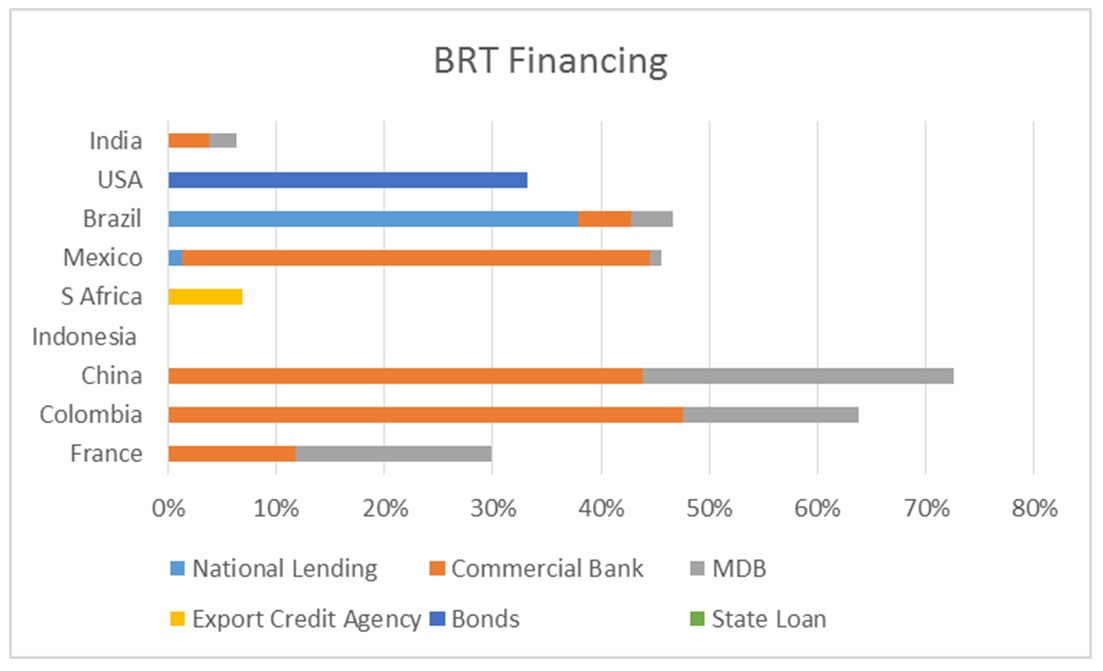

A recent study of the financing for some forty-eight BRT projects in nine countries, Best Practice in National Support for Urban Transportation, Part 2: Growing Rapid Transit Infrastructure—Funding, Financing, and Capacity (2015), indicates that only China and Colombia were debt financing more than 50 percent of the total capital cost of their BRT projects. This lower than expected average results from different causes in different countries. It indicates that many BRT systems could borrow more, so more could be built faster.

China and Colombia have both produced impressive levels of new BRT infrastructure in the past decade, and they also had the highest level of debt finance for their BRT projects, at 73 percent and 65 percent, respectively. In the case of China, municipal governments have historically found it quite easy to borrow from local commercial banks for mass transit projects, as the municipal governments are generally quite wealthy due to profits on the appreciation of urban land values. Further, some of the banks lending for BRTs are owned directly by the municipality. Several of the high-profile BRT projects included in the China sample were also financed by multilateral development banks (MDBs).

In Colombia, the national government borrowed money from several MDBs (World Bank, IDB, CAF) to build BRTs across the country. This money was dispensed to municipal governments over time (generally in five-year periods). As the funding only came over five years, the construction companies would front the money, borrowing much of it from commercial banks with whom they had long-standing relationships. This debt financing helped accelerate Colombia’s rollout of BRTs.

Brazil, which built hundreds of kilometers of new BRT systems in the lead-up to the 2014 World Cup, also did this largely with debt financing. In this case, the financing came almost entirely from two national development banks: the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) and the Caixa Economica. While this low-cost financing accelerated Brazil’s BRT rollout, there is growing evidence that it has done so without the funding to back it up, and Brazil now faces a significant debt problem.

In higher-income economies, such as France and the United States, most of the higher-income cities with aging rail properties have transit authorities facing a backlog of unmet maintenance needs. These capital requirements tend to be met through debt, usually municipal, state, or transit authority bond financing. New projects, however, are eligible for national government grants. On new BRT projects, state or local governments will often use debt finance for only 70 percent or so of the non-federal portion of the infrastructure cost (Lefevre, Leipziger, and Raifman, 2014). For this reason, the debt-financed share of new BRT projects in both the United States and France is only between 30 and 40 percent. Most transit properties are not, however, in a position to greatly increase their debt financing unless new revenue streams to back this debt are found.

In India and Mexico there are also national government grants to fund new BRT projects. The state and municipal governments responsible for implementing the projects have only needed financing for the portion not covered by the national government grant, which has lowered the borrowing needs on the part of localities for new projects.

In Indonesia, there is only BRT in Jakarta, and Jakarta has more money than it can spend in a way that is consistent with current government anticorruption protocols. DKI Jakarta has also been reluctant historically to borrow money from international development banks as it has wanted to avoid competitive bidding requirements.

17.3.2Debt Financing Options

The above study found five main sources of BRT financing:

- Bonds;

- National Government and National Development Bank Loans (NDB);

- Multilateral Development Bank (MDB) Loans;

- Commercial Loans;

- Bilateral Loans or Loans from Export Credit Agencies.

Each of these sources of financing has its advantages and disadvantages. The main differences include:

- Eligibility for the type of debt (i.e., credit rating accepted);

- Cost of the capital (i.e., the interest rate);

- Length of the credit (the repayment period on the debt) and the grace period;

- Conditions placed on the loan (conditionality);

- Transaction costs of securing the loan (time and work required to secure the loan).

To the borrower, the ideal source of financing would have a very low interest rate, a very long repayment period with a long grace period, few conditions, and minimal transaction costs. To the lender, the riskier the project or the borrower, the more precautions are put in place and the higher the interest rate. There are generally specific reasons why certain types of financing have come to dominate borrowing in the urban transit sphere in each country.

Countries should pursue increasing access to the most familiar, lowest-cost debt finance for infrastructure, primarily that which bonds and development banks provide. Countries where cities’ infrastructure development is constrained by lack of low-cost debt finance should consider programs that support improvement in cities’ credit ratings and/or lending to cities through a National Development Bank.

Table 17.1Characteristics of Different Financing Sources

| Bonds | Multilateral Development Bank | National Development Bank | Commercial Bank | Export Credit Financing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | Low | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Credit Rating Required | High | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Length of Credit Term | Long | Long | Medium | Medium | Long |

| Conditionality | Low | High | Medium | Low | High |

| Transaction Costs | Low | High | Medium | Low | Medium |

Bond Finance

Bonds issued by state, municipal, and public authorities are a popular mechanism for financing BRT infrastructure in the United States and Europe. It is likely that more cities in emerging markets with reasonably strong finances will turn to bond financing as a mechanism for financing BRT system expansion in the future.

Issuing municipal bonds requires that the municipal finances be audited by an internationally recognized rating firm like Moody’s or Standard and Poor’s. The city’s financial conditions and ability to both raise revenue and live within its means must be found sufficiently transparent and legally sound by an international bond rating company in order to provide sufficient security to bond holders. This rating process itself is not that expensive, generally costing around US$1 million to US$2 million, but bringing the accounting systems of a municipality up to a state where they are sufficiently transparent and consistent with accounting norms to secure the necessary approvals from the bond rating companies may be a lengthy and expensive process. Nonetheless, this is a process that cities should go through as they develop.

The government body receives a rating, and the cost of capital (the interest rate) will be set based on that rating. The most established municipalities and state governments in higher-income economies with perfect payment histories generally have a AAA rating, and pay interest similar to the cost of a treasury bill, making the cost of capital for municipal bonds quite low. Historically, municipal and public authority bonds have been within 1 to 2 percent of the price of a treasury bill, sometimes higher and sometimes lower. The variance between the best rated and worst rated municipal bonds is also usually around 1 to 2 percent but it can be more in times of financial turmoil (WM Financial Strategies, 2017).

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transport Authority in the United States, which financed part of the Cleveland BRT, for instance, has a AAA rating from Standard and Poor’s, allowing it to float twenty-year bonds at little more than the cost of a treasury bill (currently around 3.5 percent), while New York has a AA- rating and therefore pays around 5 percent. Maturity periods for bonds are typically long—usually at least ten years and can be up to thirty years, with no conditions and low transaction costs.

Table 17.2Characteristics of Bonds

| Bonds | |

|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | Low |

| Credit Rating Required | High |

| Length of Credit Term | Long |

| Conditionality | Low |

| Transaction Costs | Low |

Most transit investments are made by transit authorities and are financed with either general obligation bonds of the state or city government that borrows against future general tax revenues or more project-specific revenue bonds that borrow against specific revenue sources. Those that borrow against user fees such as transit fares generally do not need to be voter-approved. Other revenue bonds impose new taxes earmarked to pay for transport infrastructure such as the half-cent sales tax in Los Angeles, known as Measure R, which was passed by popular referendum in 2008 to fund transport infrastructure.

While it is often difficult for cities in lower-income economies to get bond ratings for the first time, because it requires transparent and easily auditable accounting procedures, it is generally worthwhile in the long run for both better access to capital and improved financial transparency, since bond financing has the lowest cost of capital and the least conditionality. That Mexico City, for instance, was able to issue bonds for construction of its Metro Line 12 on the Mexican Bond market, most of it at 7.1 percent interest, or 3 percent below commercial rates, indicates that bond financing should be an attractive method of BRT financing moving forward (Corrales, 2010).

Multilateral Development Banks

In lower-income economies, by far the best and most important source of financing for BRT has come from the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs). MDBs are intergovernmental financial institutions that are generally capitalized to some degree by higher-income member countries and whose purpose is to lend money to lower-income member countries (though some development banks, such as the European Investment Bank EIB, the house bank of the European Union, lend primarily within higher-income member countries).

In some countries, MDBs provide the dominant share of the overall transit infrastructure finance. The World Bank, for instance, was the main source of financing in Tanzania for the Dar es Salaam BRT, as well as for the BRT in Lima, and for one of the future BRT corridors in Pune, India. The World Bank, with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF, the Cooperación Andina de Fomento or Banco de Desarrollo de America Latina) was also instrumental in the rapid rollout of BRT in Colombia, after the success of TransMilenio Phase I in Bogotá. Two of the highest rated BRT projects in China, in Lanzhou and Yichang, were both financed by the Asian Development Bank. These ADB loans in China are one to two percentage points below the commercial interest rates, and hence are a very attractive form of project financing. The ADB’s willingness to finance BRTs has helped create incentives for Chinese cities to build more cost-effective mass transit. Currently the ministry of finance has reserved MDB lending for “pilot” projects that require technical help, but China can well afford to do more MDB borrowing, and the quality of the projects was clearly improved by ADB involvement. Expanding MDB urban transit lending in China is thus a good opportunity.

Table 17.3Characteristics of Multilateral Development Banks

| Multilateral Development Bank | |

|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | Low |

| Credit Rating Required | Low |

| Length of Credit Term | Long |

| Conditionality | High |

| Transaction Costs | High |

Multilateral development banks have significant advantages in financing sustainable urban transit infrastructure. The World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the ADB, the EIB, the IDB, and the other regional development banks offer different borrowing mechanisms for client national governments and sometimes subnational governments and commercial clients. The IBRD, for instance, currently charges the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) plus 0.85 percent for interest plus a 0.25 percent commitment fee and a 0.25 percent front end fee for an eighteen- to twenty-year variable rate loan (IBRD Lending Rates and Loan Charges 2016; http://treasury.worldbank.org/bdm/htm/ibrd.html). The other multilateral development banks offer comparable rates in somewhat different packages as they tend to compete with each other to secure borrowers. All the MDBs fund their lending by selling bonds on the international capital markets that are very low risk because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the member countries, and because governments tend to repay the World Bank before any other form of debt. They then lend the money out at a marginally higher rate than they pay for it, and they charge service fees. The World Bank has an additional loan window called the IDA (International Development Agency), which makes no- and low-interest loans as well as grants to only the countries with the lowest economies. IDA was used for the Dar es Salaam BRT (World Bank, 2013).

The advantage of MDB financing is that the interest rate is usually as low, the grace period long, and the terms as long as any other lending source, without the loan being tied to companies of a particular nationality.

The disadvantages to borrowing from MDBs, from the perspective of the borrower, are several. First, the project must be opened up to international competitive bidding. Secondly, the fees are often expensive. Third, the transaction costs are high. Projects funded by the MDBs must pass a series of project evaluation criteria to secure approval from the bank board of directors, such as internal rate of return analysis and environmental, and social appraisals. As a result, project quality and transparency is often higher; however, from the perspective of the borrower it also means more administrative work. This all takes a long time, often several years, which may be beyond the political time horizon of a politically elected project proponent. The loans may come with a variety of other additional forms of conditionality. These conditions can be used to further a variety of purposes, some oriented to social and environmental outcomes, others more related to trade or balance of payment concerns. For instance, the loan may require that the cost recovery ratio on a transit system increase fares in a way that has adverse impacts on low income people, as a World Bank loan did to the Hungarian rapid transit authority, BKV (Hook, W., 1996).

On the other hand, the loan might be more likely to be approved if it is consistent with the development bank’s stated policy goals and commitments. For instance, in 2012, the multilateral development signed an agreement to shift the US$175 billion they cumulatively planned to lend in the transport sector in the following twenty years to more sustainable modes. While enforcing this is difficult, the banks have formed the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport and associated observer organizations are now working to monitor and report progress toward these commitments. This creates incentives for the MDBs to lend more for rapid transit.

Finally, a significant problem for MDB finance of urban transit is that some of the development banks have limited ability to do sub-sovereign lending. For the World Bank, all lending to a city must be approved and facilitated by the national government. If a national government and a municipal government are from different political parties the municipality could potentially find it difficult to get a loan from an MDB. Some of the regional development banks are finding mechanisms to get around this to lend directly to cities and states without needing national government approval.

National Development Banks

National governments sometimes lend money to states, cities, and the private sector for urban transport projects. This is often done through a national development bank (NDB) that is committed to providing credit toward projects that encourage general economic development, though sometimes national governments make loans directly to projects. This can be a highly effective method for a country to ensure access to low-cost debt finance for infrastructure projects that are for critical for development, especially when credit ratings or other restrictions limit bond market access.

Table 17.4Characteristics of National Government or Development Banks

| National Government or Development Bank | |

|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | Low |

| Credit Rating Required | Low |

| Length of Credit Term | Medium/Mixed |

| Conditionality | Medium/Mixed |

| Transaction Costs | Medium/Mixed |

National Development Banks (NDBs) allow national policy makers to set lending practices and requirements according to national policy objectives, and these can vary from country to country. Typically, NDB loans to cities and states have below-market interest rates, do not require a high credit rating, have medium- to long-term repayment periods, and lower transaction costs. Conditionality can be mixed—whereas MDB loans may require opening a project to international bidding, NDB loans may allow or require national bidding. While the goals of such national bank conditionality tend to focus more on economic growth and competitiveness than on sustainability considerations, they have the potential to also support environmental or social goals with low-cost loans to sustainable modes of transport.

The world’s largest development bank is the China Development Bank (CDB), with four times the assets of the World Bank. CDB is directly involved in many rail rapid transit projects. Although it regularly lends money to the municipal investment corporations that fund the BRT infrastructure and is a main financier for urban rail projects, the CDB is not as important to the overall BRT financing picture as commercial credit or quasi commercial credit for BRTs in China. Its interest rates are not that different from that of other commercial credit available in most provinces. Also, its principal advantage is in the length of the loan repayment period and the larger size of the loans, which are far more difficult to achieve from commercial banks for rail projects.

Brazil is home to one of the world’s largest development banks, the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES), as well as National Savings Bank (Caixa Economica Federal, or “Caixa”), both of which provide the vast majority of lending to urban transit investments in China at very low rates. Since 2005, BNDES was responsible for most of the rapid transit financing in Brazil. However, in 2008, the national government began using Caixa as the lending institution for its Accelerated Growth Program (PAC) that financed many new transit systems. Until recently, BNDES and Caixa loans were at around 5 to 6 percent interest and were so much lower than commercial rates in Brazil, which often are twice as high, that they effectively represent publicly subsidized loans. This was made possible by large transfers from the national treasury and by access to worker pension funds. Recently, Brazil has announced plans to increase the interest on BNDES loans as a way of addressing Brazil’s growing debt problems.

Other countries have national development banks, but they have not had a significant role in any of the better-known BRT projects. The reasons for this are unclear, but the existence of NDBs in these countries does offer a mechanism for these countries to access financing and this could help grow their RTR. Mexico has a development bank, BANOBRAS, that has expressed willingness to finance or serve as a guarantor for BRT systems, but it has to date played a limited direct financing role in BRT infrastructure, aside from some facilitation of PROTRAM grants and UTTP loans. South Africa’s national development bank has also not been active in financing rapid transit. Colombia has recently created its own national development bank, Findeter, but so far it has not been active in financing BRTs.

Some countries do not have national development banks. While France and the United States do not, they do still occasionally give national government loans to local governments. Some highway projects in the United States, for instance, received Federal Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loans. Given the mature bond markets in these countries, the need for a development bank may not be not high, though discussions regarding creating infrastructure banks have recently been raised in the United States. Indonesia does not have a national development bank. India had a development bank in the past, but over time its role as a development bank has been diminished, and it increasingly functions like any other commercial bank.

Commercial Credit

While development banks will often offer interest rates below those of commercial lending institutions, this type of concessionary financing may not always be available. A country may not qualify for concessionary terms, or a city may have reached its borrowing cap with a particular lender. Also, development banks may be wary of lending to a project if the loan will act to crowd out interested commercial banks.

In some circumstances, the commercial lending rate may be quite competitive with a development bank, if project development costs are included. Cities may also wish to include a commercial lender in the project for several additional reasons: (1) Greater project financing expertise; (2) Diversification of financing sources; (3) Development of a successful track record with a commercial lender could be useful in subsequent project phases.

Municipal, provincial, and national governments frequently approach commercial banks to participate in the financing of major infrastructure projects such as metros and BRT. As the experience with BRT has grown, commercial lenders have increasingly viewed BRT infrastructure as a viable lending opportunity. While private banks did not participate in the infrastructure part of the first phase of Bogotá’s TransMilenio, the system’s success has spurred a competitive environment for banks vying for participation in later phases.

A commercial bank loan to a municipality for BRT infrastructure is generally assessed based on the faith in the overall municipal finances. In such cases, the viability of the BRT system itself would be only a secondary concern to a private bank since the repayment obligation lies with the municipality.

Commercial loans from private banks play a role in lending to infrastructure projects in most countries especially to private sector partners but also to some public sector transit authorities. However, in countries where there is little access to bond markets or national development banks for transit investments and where MDB loans cannot finance a majority of the projects, project proponents will resort to commercial loans from private banks to finance their urban infrastructure.

Table 17.5Characteristics of Commercial Banks

| Commercial Bank | |

|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | High |

| Credit Rating Required | High |

| Length of Credit Term | Medium/Mixed |

| Conditionality | Medium/Mixed |

| Transaction Costs | Low |

Commercial loans for public transit infrastructure occur in three basic types:

- Direct commercial lending to governments;

- Commercial lending to government owned enterprises (GOEs);

- Commercial lending to private sector investors in public infrastructure through public private partnerships.

Direct commercial lending to governments happens in countries like Mexico where city and state governments borrow directly from private banks. In other countries, like China and India, city and state governments are not allowed to borrow directly from commercial banks but can create GOEs (also called special purpose vehicles or “SPVs” in India) that can borrow from private banks.

Commercial lending to private sector investors in public infrastructure through public private partnerships is the third form of commercial lending to public transit infrastructure. In such deals, a private company will borrow from a commercial bank (in some places private firms can also borrow from development banks) to raise funds for some form of capital investment, usually rolling stock but sometimes for infrastructure as well. The private firm will also often invest its own equity into a project (though usually 20 percent or less of total project cost). These investments will then be paid back over time either through user fees or payments for service by the government or a combination of the two. While the government is not technically taking out a loan in this scenario, the private sector investment can still essentially be thought of as a mode of financing for the government itself because it mobilizes private capital up front and uses essentially public funds (via transferring fare revenue collection rights and/or additional service payments/subsidies) to pay off that capital over time. This is another effective way for cities and states to get investment infrastructure when there are restrictions on other forms of lending. However, project proponents must gauge carefully the ultimate cost of capital and corresponding risk assumption under such arrangements.

Within China, the government makes a distinction between commercial banks and “policy” banks, which more directly seek to achieve policy outcomes through lending. Though both are owned by the government, the only “policy” bank that makes loans for urban transit is the China Development Bank. The other banks, though government owned, are all considered “commercial” banks because they lend at commercial rates for commercial periods of time and at a scale comfortable to a commercial bank. This is not to say that there is not governmental interference with commercial banks. Political influence over the municipally owned banks, in particular, seems to have an impact on urban transport project lending. Loans for the projects that are a priority of the mayor yet face the greatest economic uncertainty tend to be funded by the municipally owned banks, which the city’s mayor has more control over.

Commercial loans in China are largely made to government-owned enterprises (GOEs) at the city level, which unlike city governments, are allowed to borrow directly from commercial banks. These GOEs are also controlled by the mayor and for most purposes are an extension of the municipal government, so loans are considered by the banks as direct loans to the municipality and thus enjoy lower interest rates. Most cities have municipal bus companies that are city-owned enterprises, and these enterprises tend to be in control of vehicle procurement in BRT projects. They tend to borrow from commercial banks. There are also a few private concession metro systems in China. In these deals, private investors borrowed money from commercial banks to pay for the rolling stock. The investors were repaid over time by the municipality in the form of lucrative operating contracts. The real cost of capital in these instances ended up being higher than for other available forms of financing in China, so this arrangement has not gained much traction.

In Mexico, states and especially cities have very limited means of raising tax revenues outside of the Federal District of Mexico City. State budgets are often so tight that states will take commercial loans to finance general budgets. Furthermore, in the wake of the 1994-95 financial crisis, debt ceilings were implemented, limiting states and cities from borrowing money from private Mexican banks using future federal government transfers as collateral, as these loans were a cause of the financial crisis. City and state governments are also not allowed to raise loans in foreign currencies, and some BRT projects require foreign exchange. Most rail and BRT projects in Mexico are set up—at least in part—as public private partnerships (PPPs) as a way of getting around borrowing limits and restrictions on international borrowing.

Mexico’s BRT program known as PROTRAM (a national government program funded by national toll road revenue surpluses) mandated that a project needed 30 percent private sector investment to be eligible for PROTRAM grant funds. A large part of the commercial financing in Mexico is financing the private sector investment share of these PPP BRT projects.

Thus far, India has done very little debt financing of its BRT systems. India has two major state banks, both essentially commercial banks, that played a key role in financing urban rail infrastructure, but none to date have played any role in financing BRT. The Mumbai Metro was financed in part by loans from the IDBI (formerly known as the “Industrial Development Bank of India,” and now known simply as “IDBI”) and both the Hyderabad and Bangalore Metro systems were financed in part by loans from the State Bank of India. Both of these banks retain majority ownership from the Government of India, though they function as commercial banks rather than development banks since the Industrial Development Bank (Transfer and Undertaking and Repeal) Act of 2003. As such, these loans from SBI and IDBI are private commercial loans (Rajesh, R. and Sivagnanasithi, T., 2009, p. 8).

In India, the only commercial bank financing involved in its BRT projects has been for vehicle procurement. Most BRTS in India created special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to manage BRT systems, and these SPVs tender out their operations to private operators to form a particular type of PPP. The private operators, which tend to have a contract with the SPV, use their operating contract to secure financing for the procurement of the BRT vehicle fleet. Of five BRT projects reviewed in India, three received commercial bank financing, and the loans were to the operators for vehicle procurement. In all, the loans were for less than 10 percent of the total project costs. For highways, commercial banks financed two out of three projects, although lending levels varied widely. One project was for 84 percent of total project costs and one was for 9 percent. Rail consistently received financing at higher shares of the total project costs. Four out of five projects commercially financed between 10 to 63 percent of total project costs. This indicates that India could dramatically expand its rollout of BRT infrastructure by increasing its level of commercial lending for BRT infrastructure.

17.3.2.1Export Credit Agencies (ECAs)

For some higher-income nations, Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) are a mechanism to promote national technologies and firms. A few ECAs, namely BNDES, JBIC, and the United States Exim bank, have direct lending programs in lower-income economies, and these require risk sharing or co-lending with banks. Export Credit Agencies work through commercial banks. Normally the ECA will provide a guarantee to a commercial bank, which will then provide the financing. As such it is important for operators/city sponsors to find an experienced ECA bank arranger/lender that can evaluate the BRT project and borrower risks and make a case for the ECA to provide support to its lending to the project. Currently the most successful ECA finance arranger for BRT projects is HSBC but Citibank and BNP have also worked on ECA financings for bus and coach projects in Mexico and Colombia.

Commercial Bank Loans supported by insurance from the ECAs can be extended to borrowers in countries with lower economies if there appears to be a benefit to the country with a higher economy’s interests. Thus, if markets exist for construction companies, vehicle manufacturers, and fare equipment vendors from higher-income nations, then ECA-supported loans are a possibility for lower-income cities.

In the rail sector ECA financing has provided extremely low interest loans with very long repayment terms and minimal transactions costs. Export credit agencies sometimes offer intergovernment loans for rail projects at rates far below the cost of similar (long) term United States Treasury bills. The limitation of such loans is that they tie the borrower to procurement of goods and services from corporations from the lending country.

Table 17.6Characteristics of Export Credit Financing

| Export Credit Financing | |

|---|---|

| Cost of Capital | Low |

| Credit Rating Required | Low |

| Length of Credit Term | Long |

| Conditionality | High |

| Transaction Costs | Medium |

While to date these bilateral lending institutions have not been involved in the infrastructure side of BRT projects, they have been involved in lending for BRT vehicle procurement, and several of them would be open to lending money for BRT infrastructure if their own construction companies were involved.

This form of “tied” aid may act to ultimately compromise the intended direction and quality of the project as well as increase the overall capital cost. Bilateral lending in the urban rail sector has led to considerable distortions in decision making, creating a powerful incentive to build expensive urban rail systems where BRT would have been just as effective and far cheaper and faster to build.

Bilateral and export credit agency loans were not a significant form of BRT infrastructure financing for any country. There have been significant ECA loans for urban rail projects, however. For Indonesia, there was just one export credit loan, for the Jakarta metro. The Jakarta metro was financed by a loan from JICA (Japanese International Cooperation Agency) at just 0.2 percent interest with a ten-year grace period and a forty-year repayment period (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2017). This is a highly subsidized loan, far below the cost of any alternative sources of financing in Indonesia or internationally. However, the loan is tied to procurement from Japanese construction and rail companies for most key elements of the project. These can end up being monopoly supply relationships that can increase the long-term cost of the supply of spare parts, which constitute a large share of transit system operating costs.

India has also relied on export credit agencies for rail projects. The Delhi metro is also being financed by extremely low interest loans from JICA, which also financed the Kochi metro and the Bangalore metro. AFD (L’Agence Francaise de Developpement), the French development agency, also provided loans for the Kochi and Bangalore metros. In many of these cases, the availability of very low interest export credit financing from the country providing the technology can play a key role in the selection of rail technology. South Africa, China, and Brazil also received bilateral loans for a small number of urban rail projects, though it was a relatively minor share of their overall financing picture.

For BRT, ECA was used only for vehicle procurement. Many of the BRT projects also turned to the ECAs of the countries where vehicles are manufactured. Bogotá’s TransMilenio and Johannesburg’s Rea Vaya both relied on Brazil’s BNDES bank for vehicle procurement, and Mexico City’s Metrobus and TransMilenio relied on guarantees from the Nordic export credit agencies. The interest rates (1 to 2 percent, or 100 to 200 base points below the market rate) on these deals were closer to commercial interest rates but generally below the interest rates that would otherwise have been available from a commercial bank.