17.2Funding BRT’s Capital Costs

Money often costs too much.Ralph Waldo Emerson, author, poet, and philosopher, 1803–1882

The capital costs of BRT systems are generally funded in a manner similar to other medium- to large-scale capital projects of the same implementing agency, which is usually a level of government (municipality, state, or national) or a government-owned enterprise established under one of these levels of government.

17.2.1Sources of Funding by Level of Government

Funding the capital costs of a BRT system depends on which level of government is leading the BRT project, and its track record at managing projects on a similar scale.

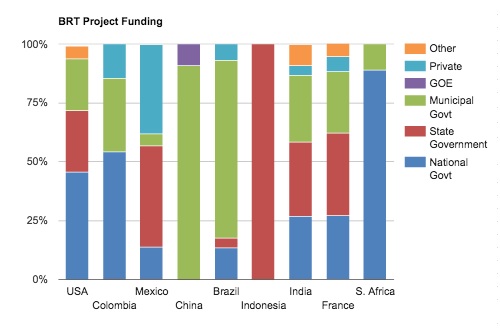

In the chart below, a large sample of BRT systems was broken down by the source of the capital funding.

The funding details of forty-eight BRT projects in nine countries were analyzed in the report Best Practice in National Support for Urban Transportation, Part 2: Growing Rapid Transit Infrastructure—Funding, Financing, and Capacity (2015), and the source of funding was broken down into the following five main sources of funding: +

- National government; +

- State government; +

- City/metropolitan governments or transport authorities; +

- Government-owned entities; +

- Private sector backed primarily by user fees.

Funding sources in this case refers to the level of government that has ultimate spending discretion to choose a project and takes ultimate responsibility for paying for the project, either directly or indirectly by agreeing to service the debt. If taxes are collected by a national government and the revenue is passed on to a city or metropolitan government to use at the discretion of the city, then the funding source is considered “city.” If the funds are invested by a private company or a government-owned enterprise (GOE), they are marked as such. Such investments of private companies or GOEs are usually made by borrowing money against the expectation of future public funds in the form of user fees and/or fees from concession contracts paid by the government.

Normally, infrastructure accounts for 85 to 90 percent of total capital costs, while the vehicle procurement and other equipment makes up only around 10 to 15 percent of the total initial capital cost. In the cases listed below where “private” investment has been used to fund the capital costs, as in the case of Mexico, Colombia, and India, this normally covered the vehicle fleet procurement. Generally, where the source of capital was “private,” there was the expectation that fare revenues would be sufficient to cover the initial private investment in the vehicle fleet. Only in Mexico was there an attempt to get fare revenues to cover part of the original infrastructure investment, and these systems are proving to not be financially viable. As such, BRT project teams should assume that infrastructure costs will ultimately be paid by the government in some form, and user fees will hopefully be sufficient to cover all or most of the operating costs.

Generally, where possible, municipalities take the lead. When municipalities are weak, or where a capital city area is designated as a state or provincial level of government (as is the case for Jakarta, Delhi, and Mexico City), state or provincial authorities carry the primary funding responsibility. Normally, government-owned enterprises are controlled by one of these levels of government. Where both municipalities and states are too weak to raise the necessary revenue, or where accelerating a national urban mass transit program is a national priority, national authorities have stepped in to meet the funding gap.

Countries can be broken up into the following categorizations: those where the municipal government provide the majority of funding (China, Brazil); those where state governments or national capital areas play the key role (Indonesia); those where the state government, state-owned enterprises, and the private sector play the key roles (Mexico, India); those where the national government and the city play the key role (Colombia); and those with a fairly even mix of funding sources (United States, France). The ultimate source of government revenue used to pay for the BRT capital costs tends to follow the general sources of government revenue for the level of government that takes the lead in funding the BRT project.

17.2.2Sources and Reliability of BRT Capital Funding

The best sources of capital funding are those that sustainably and predictably raise sufficient revenues to fund system construction, rolling stock procurement (if necessary), system expansion, and ongoing maintenance. Developing a new and untried source of funding is generally a long and cumbersome process, so a BRT project team should always first try to fund its project with well-established mechanisms for funding municipal public works.

To the extent that everyone has a stake in a vibrant economy, a healthy environment, and desirable public spaces, public transit infrastructure investment is often considered a reasonable use of general taxpayer funds. Thus, the forms of taxation that have generally proved to be the most reliable sources of capital investment funds in a particular country are usually the most secure source of BRT infrastructure funding.

In addition, sources of funding that increase the costs of motor vehicle ownership and use to something closer to its real social cost have the simultaneous benefit of encouraging people to use transit. Historically, private motorists have not been required to pay for the full social cost of their choice of travel. Motorists also tend to be among the wealthier members of society. As such, many societies find it reasonable to tax or charge motorists, and use these revenues to finance transit infrastructure investment. This may take the form of fuel taxation, road user fees, parking charges, or registration and licensing fees.

While it is generally best to have the direct beneficiaries pay the capital costs, and since fare revenues and advertising revenues are never sufficient to cover the necessary capital costs of a BRT, many have argued that property owners along a new BRT corridor should also pay for part of the BRT capital costs since they may benefit from the new BRT. Sometimes new real estate development will occur along a new BRT corridor, attracting additional property tax revenues, and existing property owners will benefit from increased rent revenues and property values as a result of the BRT investment. In theory, these increased property values can be taxed and earmarked to a transit investment. This can be done indirectly by using city property tax revenues in general to pay for new BRT infrastructure, or more directly through special tax assessment districts in the area served by the new transit link, or tax increment financing mechanisms, where increases in property tax revenues (but not of the rates) are earmarked to a specific transit investment. In practice, however, the uncertainty of such funds in higher-income economies, and the underdeveloped property tax regimens in lower-income economies, have limited the application of this type of funding for BRT systems to date.

Many have seen the growth of metro systems funded by private consortia in exchange for development rights on public land, and considered the possibility of similar funding and financing mechanisms for BRT systems. To date, however, while there are public-private partnerships (PPPs) funding BRT systems, such a PPP funding mechanism linked to a public land development deal has only been applied to BRT projects in a limited way. While this may evolve, as this would be a financial innovation in most countries, it should only be considered as a last resort.

BRT Capital Funding from General Tax Revenues

By far the most common source of funding for BRT capital costs not covered by fare revenue is general budget revenues, sometimes specifically earmarked for transit. Most typically, these are value added taxes, or sales taxes, though in a few cases they are a form of payroll tax.

Earmarked taxes are largely a higher-income economy phenomenon. In Europe and increasingly in the United States as well, it is often accepted that mass transit is a social good for a state or metropolitan area. In this way, earmarked taxes of various sorts, or public-transport-specific levies, at both the state and municipal levels, are being used to support not only capital costs but also operating losses of transit systems.

In a survey of multiple countries, funding for mass transit was the stablest in France. There, the national government collects an urban mobility tax on employers as part of a payroll tax, and channels it to departments and cities for them to use on transport largely at their own discretion. France’s BRT systems as well as its LRT systems are largely funded in this way, and France has outperformed most other countries in terms of the expansion of its rapid transit networks.

In higher-income economies, as BRT services are generally part of a larger package of transit services, which are loss making as a whole, fare revenues rarely cover operational costs. Thus, these same public funds are used not only to cover infrastructure but also to cover vehicle procurement, fare collection systems, operational control systems, and other forms of capital investment that in lower-income economies would more likely be covered by the fare revenue.

In the United States, the main source of capital investment in new mass transit infrastructure for many years was the national government, either in the form of congressional earmarks (one-off capital grants) or as New Starts/Small Starts grants from the Federal Transit Administration. In recent years, however, the metropolitan areas most rapidly expanding their transit systems are almost all doing so with a large contribution from state government-level earmarked funds, generally approved by voters through referenda. A few cities are also passing referenda for transit-specific spending. The source of these funds varies. In most of the United States, bonds approved by taxpayers are backed either by general tax revenues, or by earmarked additional sales taxation (relatively regressive). The State of North Carolina, for instance, funded LRT in Charlotte, with one-half of 1 percent of the state sales tax set aside for municipal public transport projects. Similar measures are in place in Washington State, Colorado, and elsewhere. New York State has a whole host of special taxes that are earmarked to finance public transport capital investments, including mortgage transfer taxes, and a percentage of the sales tax. There are proposals in a few states (Massachusetts, for instance) to fund new transit investments from an additional state income tax on the wealthy. As BRT services are all operated as part of transit authorities that are on the whole loss making, these same sources of public funds are generally used to finance vehicle procurement, fare collection system equipment, and any operational control technology that may be in place. The funding structures are similar to those for new urban rail projects.

After France, China has been rolling out new mass transit infrastructure at the fastest rate of those countries studied. China’s municipal finances are unique, and extremely strong. Its BRT systems have been funded by municipal governments virtually unaided by other levels of government. The boundaries in most Chinese municipalities extend far into peripheral urbanizing areas, and urbanizing land is often annexed to the municipality. Land is all officially municipally owned and then leased to private investors. Thus, when the land is rezoned from rural to urban use, there is an enormous increase in its value, and this value is captured by the municipal government. More than half of urban infrastructure in China is funded by this form of value capture. Otherwise, transit infrastructure investments are funded primarily by corporate income taxes. For the near term at least, and barring any crash in urban land value, these have proved reliable sources of revenue for rapid transit development in Chinese cities. Most of the vehicle procurement in the BRT systems was done by the municipal bus company, which tends to receive operating subsidies and subsidies to buy new vehicles from the municipal government, funded from the same sources. In Guanghzou, the vehicle operators are semiprivate, and vehicle operations are profitable. Many of the vehicles were ordinary, but some new special BRT vehicles were purchased out of the company’s profits. Funding and financing for urban rail in China follows similar lines.

In Brazil, BRT infrastructure is largely funded by municipal governments, and municipal government budgets are heavily dependent on value-added taxes on businesses. The vehicles and fare collection equipment are generally funded fully from private investment backed by the fare revenue, with the exception of in São Paulo where the private investment is in part backed by operating subsidies. This contrasts with urban rail projects, which tend to be financed by state governments in Brazil, but state governments have a similar dependence on value-added taxation.

In Mexico, Mexico City is a federal district with powers similar to that of a state, and since the country’s economic activity is concentrated there, the state VAT tax receipts are sufficient to pay for a significant share of the city’s BRT infrastructure needs. Outside of Mexico City, BRT projects depend more on state and national funding. BRT vehicles tend to be paid for by private operators, though these same sources of government tax revenue subsidize part of the BRT vehicle procurement cost.

In India, BRT capital investments are largely funded with a combination of national government JNNURM (Jamal Nehru National Urban Redevelopment Mission) grants, and from the same state-level value-added-tax revenues that fund most large public works projects. In some cities like Ahmedabad, the municipality also pays for a significant part of the BRT infrastructure. This is quite different from urban rail projects in India, where the source of funding is unlikely to include any funding from the municipality. In some Indian cities, the vehicle procurement is covered by private investment, while in other cities like Pune BRT vehicle procurement is covered by a grant of new vehicles from the national government through the JNNURM program.

In Indonesia, the government of DKI Jakarta (Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is a state-level government. Jakarta pays for all of its BRT corridors out of general budget revenue. For most phases DKI Jakarta also funds the vehicle procurement and ticketing equipment using the same general tax revenue of the city. This differs markedly from urban rail, most notably with the Jakarta metro, where the national government funds more than half of the total capital costs.

BRT Capital Funding from Fuel Levies and Other Motor-Vehicle-Related Sources

There are obvious merits in raising revenues from motorists to fund BRT capital costs. The higher costs imposed on motorists incentivizes a shift to public transport, which generally results in overall economic benefit as the negative externalities arising from motoring are reduced.

Dedicated revenue streams from petrol taxes are potentially a very good ongoing source of funds and can help establish a long-term sustainable basis for financing BRT development and expansion. Fuel taxation is both a lucrative revenue source as well as an effective mechanism to help discourage car usage. For those municipalities that can gain access to fuel tax revenues, the possibility of funding much of the BRT system through such a tax is quite good.

In lower-income economies, the use of fuel taxes to fund urban rapid transit is common, though earmarking of the funds is relatively rare. In Colombia, municipalities are allowed to levy local fuel taxes up to 30 percent of the retail price of gasoline, and these fuel tax levies provide much of the municipal counterpart funding for most of Colombia’s BRT systems. Bogotá’s TransMilenio has benefited greatly from the proceeds of a petrol tax that is partly dedicated to public transport. Approximately one-quarter of the first phase of TransMilenio was funded through the local petrol tax revenue, and most of the BRTs outside of Bogotá use local gasoline tax revenues for the 30 percent of municipal matching funds necessary to receive national funds.

About one-third of the fuel taxes collected annually by the national government of South Africa goes to subsidize the national highway program’s deficits, and the remaining two-thirds are spent on urban transit (Van Ryneveld, 2010). These amounts are not earmarked for urban transit or urban transport, but it works in a similar way.

In Mexico, outside of Mexico City, states depend heavily on the formula-based distribution of national government funds, many of which come from the sale of oil by Pemex, the former state oil company. As such, though the BRT systems outside of Mexico City are largely funded by state government general revenue, the ultimate source of many of these revenues is from profits from the national oil industry.

In Indonesia, funding for urban transport comes from provincial-level VAT, and national government-collected VAT, but as in Mexico much of this comes from oil and other extractive industries. The recent decision of Indonesia to remove oil subsidies could make more national funding available for urban transit investment, though to date the national government has only been willing to fund rail projects or the vehicle procurement side of projects labelled “BRT” but which did not reach the minimum definition of BRT.

In higher-income economies, the use of fuel tax revenues for rapid transit capital investments is also common. In the United States, a significant portion of the BRT projects have been funded by the Federal Transit Administration out of New Starts/Small Starts, which has received a dedicated portion of the national gasoline tax since 1970. A fixed percentage of this is earmarked for transit, creating a reasonably stable funding stream. The federal funding is available for infrastructure, rolling stock, and fare collection equipment. However, the gas tax was never pegged to inflation and faces declining revenues, forcing city and state governments to increasingly turn to earmarked taxes collected at the state level to fund urban transit.

In the United States, some states also have gasoline taxes that are used to fund infrastructure, ranging from simple gasoline taxes to indirect fuel taxes imposed on oil companies called “Petroleum Business Taxes.” Using surpluses from toll revenues is also common. In the New York City metropolitan area, the MTA funds its capital program in part from the surpluses collected on bridges and tunnels by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority.

In Mexico, outside of Mexico City, the other main source of funding for BRT systems has been grants from PROTRAM, a national government funding program that is funded in part from surpluses (above the cost of maintaining the road) collected on intercity toll roads controlled by the national government.

A few countries also fund infrastructure from vehicle licensing and registration fees. Vehicle ownership may not seem directly related to usage, but there is some evidence to suggest a relationship. Once a motorized vehicle is purchased, the convenience of use often induces additional trips (Gilbert, 2000). Further, once an individual makes a financial commitment to a vehicle, there is a psychological preference to maximize the vehicle’s use. Thus, discouraging vehicle ownership can help shift patronage to public transport. The financial disincentives to vehicle ownership also can produce revenues for public transport development. Vehicle licensing fees are a part of urban transit infrastructure financing in China and a few other countries, but a relatively modest one.

A number of different forms of motor vehicle charging are used to fund mass transit in other cities, but not specifically for BRT projects. Congestion charging and electronic road pricing has served as an effective mechanism to raise revenue for urban mass transit. In London, as the fees stopped increasing under Mayor Boris Johnson, the effectiveness of the measure for limiting congestion receded, but it continues to raise revenue for Transport for London. In Singapore, where charges have better kept pace with congestion levels, it also helps fund Singapore’s extensive urban rail network. Though there have been advanced discussions in a number of cities in lower-income economies about adopting either congestion charging or eco-charging (São Paulo, Mexico City, and Jakarta have all developed reasonably detailed plans), to date it has not caught on in lower-income economies.

In the United States, “HOT” lanes, or “high-occupancy + toll” lanes, are increasingly popular on congested urban highways. Seattle is currently developing a highway-based BRT system that will in part be financed by toll revenues on HOT lanes that are intended to roughly vary with congestion levels. While it is too early to tell whether this will mature into a full BRT system and whether HOT lane toll revenues will be an important element in the system’s financing remains to be seen, this looks to be part of an emerging trend. As electronic toll payment systems, such as E-ZPass, become ubiquitous, it is likely that road user fees of various forms will become a growing source of mass transit revenue.

Parking fees could be another source of BRT infrastructure funding. Some recent successes in increasing charging for parking have only in rare instances raised funds sufficient to play a significant role in BRT financing. Chicago auctioned off the right to collect all of its on-street parking levies for seventy years for about US$1 billion. The funds were not specifically earmarked for transit. Chicago negotiated a relatively poor deal (twenty years would have yielded roughly similar funds). Recent successes in Mexico City with on-street parking charging have raised revenue only sufficient for streetscape improvements. Cities could theoretically consider earmarking street parking levies for rapid transit, but the sums involved are in most cases more likely to make them useful for covering any projected operating losses.

A “parking space levy” is a technique that could hold advantages as a financial source for a BRT project. A parking space levy imposes a tax on all nonresidential parking spaces, regardless of whether the space is utilized or not. Examples are to be found in Australia and Singapore. In 1992, Sydney initiated a parking space levy for nonresidential parking spaces in the central and northern parts of the city. An annual levy of A$200 (US$150) was applied to each parking space (Enoch and Ison, 2006). This has now risen to A$800 (US$615) in the central business district and A$400 (US$308) in other business districts. The parking levy is currently returning approximately A$40 million (US$31 million) per year to the city (Litman, 2006a). Landowners must pay the fee on all parking spaces, whether the spaces are actually being utilized. If an unmarked lot is utilized for parking, the Sydney municipality determines the number of space by “dividing the total area by 25.2 square meters, which takes into account parking spaces and access lanes” (Litman, 2006a, p. 6).

Perth, Australia, also successfully adopted a “parking license fee” in 1999, which was applied to all on- and off-street nonresidential parking spaces. All revenues from the Perth program go to supporting the local bus system (Enoch and Ison, 2006).

Beginning in 1975, Singapore assessed a US$35 monthly fee on nonresidential parking spaces. This fee provided approximately US$25 million in annual revenues. The cost to administer the program was relatively low at approximately US$30,000 (US$18,000) per month (Enoch and Ison, 2006). When the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) was introduced in 1998, the authorities decided to phase out the parking levy.

It should, in principle, be possible to utilize the property tax administrative system to implement parking levies, where such a system exists, in which case additional administration costs are potentially containable.

Property Development as a Source of BRT Station and Terminal Funding

Some BRT systems have leased or sold development rights at key stations or transfer terminals to developers in exchange for the developer paying all or part of the station or terminal development cost. This practice is more established for metro projects, but is catching on in BRT systems. In metro projects, many metro companies will often take a large parcel of land to build the station, in order to build the station using cut-and-cover. Once the station is built, or as part of the construction of the station, the land above the station then becomes developable. Because the large parcel was necessary for the metro construction, most legal systems will allow the land to be taken by eminent domain for this public purpose. In a few cases, such as the Tehran Metro, some US$400 million was raised in investment funds that were then put back into metro construction. Hong Kong’s MRT famously uses the proceeds of property development to raise investment capital for infrastructure.

Though less used in BRT systems, there are a few examples of similar funding mechanisms emerging. Because the amount of land needed at most BRT stations is fairly modest, and most legal systems do not allow the excessive condemnation of land by transit authorities purely for development purposes, the development potential is generally lower than for metro rail systems, but some precedent does exist.

Property can sometimes be developed above or under BRT stations. Perhaps the best-known example of aerial property development is Brisbane’s Mater Hill station. Shops and a hospital have been constructed over the exclusive lanes of the Brisbane busway (figure 17.2). Proceeds from this property development have been utilized to build the BRT system’s infrastructure.

In China, in the Lanzhou BRT system, shopping malls were built underground directly under the BRT corridor. As this did not require any new land acquisition, it could be done by the municipality’s construction companies, and the proceeds used to defray project costs.

Transfer terminals in trunk-and-feeder BRT systems are sometimes large enough to anchor a real estate development, and some or all of the cost of the transfer station can be covered by a private developer. For example, a new transfer station between a busway trunk line and its feeder buses in Belo Horizonte was financed by a private developer in exchange for the right to build a shopping mall adjacent to the station. Belo Horizonte built a second transfer station on the same model in time for the FIFA World Cup in 2014. Mexico City built several new bus stations, one of the terminals for a BRT to the State of Mexico, at the terminals of the metro system. Called Cetrams, one at Ciudad Aztecas links to the Mexibus BRT line in the State of Mexico. The developer paid for the development of the BRT terminal station in exchange for development rights for a shopping mall over the new terminal on the site of the old bus terminal. Others are moving forward under a similar model.

Financing BRT infrastructure through land banking has not yet been done, largely because land banking is not legal in most countries that have BRT systems. Land banking is the purchase of properties adjacent to the stations of a future mass transit system by the system developer, only to be sold at a later date once the land has appreciated in value due to the completion of the new mass transit system. This was a common practice in Singapore and Hong Kong for their rail systems.

Air Rights, Special Transit Area Property Tax Assessment Districts, Tax Increment Financing

In theory, taxing the gains to property owners from land rents resulting from a government improvement in rapid transit infrastructure serving the properties would be one of the fairest methods of financing BRT infrastructure. In practice, however, there are a number of reasons why this is rarely done.

In lower-income economies, it is rarely done because even basic property taxation is still only emerging as a source of government revenue. The ability of the government to capture any positive land value impacts of a BRT system requires that the municipality has the means to collect basic property or land taxes. In many lower-income economies, site ownership rights, particularly in poor neighborhoods, are not that clearly defined (figure 17.5). Establishing basic property tax collection remains the next priority in many municipalities in lower-income economies.

In higher-income economies, Europe has relatively high income and fuel taxation, much of it collected nationally and transferred to local levels of government. There is property tax collection but it generally makes up a relatively modest share of municipal revenue. U.S. cities rely heavily on property taxation, but there are many competing urban demands on these funds. In general, cities in the United States are relatively poor because many of the middle- and upper-class residents of a metropolitan area live in suburban areas beyond the city’s tax authority.

Additional property taxes applied only to special tax districts in an area where a new BRT is being built, or earmarking of increases in property tax revenues in a zone where a new BRT is being built (tax increment financing, or TIF) has been used to fund some urban rail projects in the United States. They have been used on the Central Loop BRT stations in Chicago for a few stations, but TIF is more typically used for urban development.

In lower-income economies, municipalities lack the administrative capacity to handle such a tax, and in higher-income economies, governments are moving away from these instruments because they are unreliable. Property impacts of a new project are unpredictable and subject to business cycles in the property market. The study More Development for Your Transit Dollar (2013) indicates that the quality of the transit investment is a relatively weak predictor of whether land will develop around it. Far more important is the inherent market potential of the land and the degree to which the municipal government uses other tools at its disposal to channel new development to station areas along the BRT corridor, such as zoning, land assembly, site preparation, other infrastructure improvements, and other actions. To make transit-oriented development successful, other government investment is also generally required, and these other urban redevelopment investments may be a better use for TIF funds. However, BRT stations and terminals with architectural merit can increase commercial land values nearby as BRT becomes an urban amenity. Also, the transit-only benefits of very nice BRT stations can sometimes not be justified on purely transit benefit grounds, and using property-tax-tied funding to enhance the aesthetics of BRT stations is worth considering.

In many cities, the right to develop a site in a particular manner must be formally approved by the local government. Zoning ordinances may also restrict a site to a particular type of development. The auctioning of the right to develop a site can be a significant revenue source for a new public transport system.

The commercial opportunities around new public transport stations can make the auctioning of development rights a financing option to consider. The selling of development rights is not mutually exclusive of other property taxation sources.

São Paulo has been at the forefront of lower-income-economy efforts to raise urban development funds from the sale of air rights. Certificates of Potential Additional Construction (CEPACs), or tradable air rights, allow developers who wish to increase the density of a planned development on their property to purchase the right to add density if the property is in a strategic urban growth area. The revenue raised from the sale of CEPACs has to be used for urban investments into the strategic urban growth area. Thus far, CEPACs have yet to be used for BRT projects, but they have been discussed as a possible source of financing for the proposed BRT corridors on Celso Garcia and Radial Oeste (Murakami, 2015).