16.6Company Formation

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, writer, 1900–1944

One of the biggest challenges is transitioning a group of informal public transport industry owner-operators into high-quality modern vehicle operating companies. Compensating impacted transit owners in the BRT corridor is not the only consideration when hiring a VOC composed primarily of impacted owners to operate the BRT services. The BRT authority should also make sure the company is successful and able to provide the best quality of service at the lowest price over the long term. There is a big difference from a management perspective between owning and managing a few individual buses or minibuses with route licenses and owning shares in a modern bus company with integrated fleet management and optimized maintenance regimens.

Successful VOCs have a few things in common. All of them have competent senior management. They also have found sufficient working capital. All of them work out of a secure depot, either provided by themselves or by the city. And all of them have integrated fleet ownership and management, meaning that the vehicle fleet is owned by the company and not its individual owners, and the maintenance of the fleet is done as a fleet and not as single vehicles owned by separate individuals. Successful VOC attributes include:

- Skilled senior management;

- Sufficient working capital;

- A secure depot;

- Integrated fleet ownership and maintenance.

Some of the most successful BRT VOC companies are joint ventures between the former impacted owners and larger international companies that brought with them the possibility of placing large bulk orders of spare parts directly with spare parts manufacturers. Some brought with them skills from trucking and logistics that have optimized the deployment of staff, the utilization of vehicles, and optimized maintenance regimens. Other larger vehicle operating companies have their own credit history with major banks that lowers their cost of credit. And some of them already have their own depots.

Not only the city and the BRT customers, but also the existing owners receiving compensation in the form of shares in the new VOC, have a big stake in the commercial success of the VOC. Shares in a poorly managed company that is not in a position to win contracts on future BRT corridors and in other cities is going to be worth less than shares in a competitive, fully professional BRT operator.

It is therefore important to explain to impacted owners that they can become shareholders of the new operating company, but that as shareholders they may not play a direct role in the management of the new company. If the impacted owners are not very sophisticated, they may not think strategically about the long-term interests of the company. It may in some instances be advisable therefore to make them “preferred” shareholders without voting rights. As shareholders they will need to hire the management team, and this management team may not necessarily be the best if it comes from within the ranks of the impacted industry.

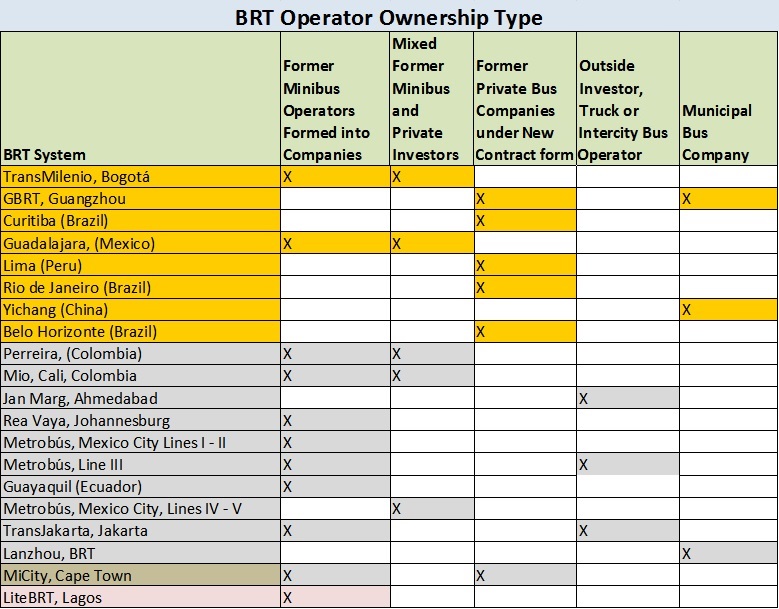

Table 16.3Select BRT system operators by ownership type.

Courtesy of Walter Hook, BRT Planning International, LLC.

In most of the Colombian BRT systems, the BRT VOCs were consortia between national and international bus operating or trucking companies and the impacted owners of the route licenses, which tended to be large bus enterprises. This pairing has worked well as it compensated the impacted owners, utilized the management skills that were already present at the bus enterprises, and brought in outside management skills from the joint venture partners where this was needed.

In some cases, it is difficult to form consortia between impacted owners and major companies. Sometimes the impacted owners are not comfortable working with larger, more established vehicle operating companies (VOCs) and vice versa. In South Africa and Mexico, the BRT VOCs tend to be dominated entirely by the impacted owners, who in turn went out and hired the necessary management teams. Some hired individuals to fill the management positions, and others hired firms.

It is fairly typical to have the bus supplier maintain the vehicles under a medium term service contract until the new BRT VOC has mastered the skill of bus maintenance. This is very expensive in the long run so the sooner the VOC is competent to take over the maintenance the more quickly the firm is likely to be profitable.

In cities where there are already established vehicle operating companies with integrated fleet management, or in cases where there were no impacted owners, the issue of management skill is less critical. In Brazil, most of the BRT systems are operated by the same big private bus companies operating under zone-based gross cost contracts that emerged in Curitiba in the 1960s and in most other cities of Brazil by the 1990s. Most of them have competent management. In China, and parts of India, the BRT systems are operated by municipal public bus companies. Although these municipal operators can be obstacles to improvement service provision, they generally have the basic skill to provide the service. Ahmedabad and Guangzhou are exceptions. Bus operations in Guangzhou were put on a commercial footing already in the 1990s and the BRT is operated by three consortia, all of them a mix of public and private ownership but operating as commercial companies. Ahmedabad’s BRT was built where there were no competing bus operations, and a private firm out of the trucking industry was hired.

A VOC typically has several key senior management positions that need to be filled with qualified staff:

- A managing director/chief executive officer/general manager;

- Financial manager;

- Operations manager, in charge of bus and driver dispatch, coordination with the BRT entity on bus schedules, monitoring bus arrivals and departures and driver performance, optimizing operations and control, etc.;

- Technical manager, in charge of the depot, workshops, and maintenance systems;

- HR manager.

Typically, whether the operating contract with the VOC is tendered or turned over to the impacted operators, the BRT project team on behalf of the city needs to require that the company demonstrate that it has a competent management team in place.

If the contract is tendered, if the city is allowed to have the tender competed on both quality and price, then the qualifications of the management team were a critical part of the evaluation of the quality score of the tender. If the tender can only be done based on cost, or if the contract is to be negotiated with the impacted owners, then demonstrating that a competent management team has been selected should be part of the minimum qualification requirements. The board of directors has to present a management plan indicating how the company will be staffed and resourced, and to demonstrate that sufficient skills, expertise, and experience have been brought on board to fulfill the conditions of the contract.

There are three basic ways to attract qualified management:

- Find qualified management from within the VOC’s own ranks;

- Have the VOC partner with an experienced BRT operator in a consortium;

- Have the VOC partner subcontract the management to a qualified BRT operator.

If the impacted owners are already reasonably sized corporate entities with business skills, it is possible that they can draw many management positions from within their own ranks. For instance, in Brazil, where the bus industry has been largely private since the 1990s and the big bus operating companies are corporate entities with existing management structures, finding qualified management from within the bus industry should be relatively easy.

If the industry is not yet corporatized and is controlled mostly by individual owner operators, getting skilled corporate management will be a bigger challenge. The safest strategy is to require joint ventures between the impacted owners and formal bus operators to form the new VOC. This has the advantage of allowing experience to be shared. Ideally the operator will have experience operating BRT companies, but often an intercity bus company or trucking company can learn how to manage a BRT operation. It is possible, however, to have the impacted owners sign a management contract with a qualified firm to manage the company, or to hire talented individuals to manage the company on behalf of the shareholders.

16.6.1VOC Formation in Bogotá

The discussion of BRT VOC formation begins with Bogotá, because the companies that emerged out of TransMilenio went on to successfully operate BRT systems in a number of other cities, not only in Colombia but also in Peru and other Latin American countries.

Bogotá did not make a political commitment that no adversely impacted license owner, bus owner, or driver would be worse off, but it did give impacted owners competitive advantage in the tender. In Bogotá, bus “enterprises” owned the licenses and small individuals owned the vehicles. Thus, the bus enterprises had more management experience, the capital needed to procure the new vehicles, and the political power to block the entire project. As such, the bus enterprises became the natural basis for the new BRT VOC companies.

To ensure that both the bus enterprises and the bus owners became owners of the new BRT operating companies, the tender required that the company have “experience operating buses” in the affected corridors. This was basically a way of ensuring that all of the bus “enterprises” would win part of the new contract. The contract also required that at least 15 percent of the shares of the new company be owned by affected bus owners whose names were on the city’s list of impacted owners. They had to demonstrate experience operating public transport in the specific BRT corridor (meaning specifically the affected owners). Operating public transport elsewhere in Bogotá also gave points, though somewhat fewer.

Of this 15 percent of the shares, the maximum number of shares that could be given to any one person was only 0.15 percent in order to ensure that most of the affected owners would be able to get at least some small share. If a person wanted more than this 0.15 percent of the shares in the new company, he or she could buy more, but then these shares did not count toward the 15 percent of shares from affected owners.

The contract also required that three vehicles be turned over to the government for scrap for every one bus that needed to be bought. The company was required to scrap a minimum number of old vehicles per each new vehicle procured. This requirement meant that those adversely affected bus owners would be able to sell their old vehicles to the new company and get some compensation either in the form of cash payment or in the form of stock in the new company. The contract also forbade the selling of stock to outside parties for five years to protect the indigenous operators’ control.

These affiliated enterprises and cooperatives were not modern bus companies. They did not own most of the vehicles under their control, so there was no collective fleet management. The bus operators were also not generally their employees, so there was no collective staff management, no standardized maintenance regime for the vehicles, nor any of the other critical attributes of a modern bus company.

The tendering documents were created in such a way that they guaranteed that the winning Phase 1 companies would be owned mainly by the existing affected bus enterprises. As of the completion of Phase 2, 98 percent of the transport companies in the city owned shares in one of the seven operating companies.

Each company also had to demonstrate that it had the minimum required equity. The minimum equity requirement was 15 percent of the value of each bus being offered in the tender (each bid offered a total number of vehicles within a given range). They also had to demonstrate that they had financing for the remainder of the vehicle procurement cost. If the company could find a financial institution willing to lend money for 95 percent, then the equity share could be lowered to 5 percent.

The operating companies also had to demonstrate that they had a qualified management team with experience operating large fleet bus companies. Forming a joint venture with an experienced international partner won extra points in the bid.

These bidding criteria, which were informally negotiated with the bus industry during the engagement period, gave the existing bus enterprises a significant advantage in winning the tenders. As a result, virtually all the bidders were companies dominated either by existing bus enterprises or outside investors who found partners among the existing bus enterprises.

Beyond the terms of the tender, the share structure of the new vehicle operating companies was not dictated by the government, but rather was sorted out within the new companies internally. Shares were awarded based on paid-in capital, on the number of vehicles turned over to the parent company to meet the scrapping requirement, and on the public transportation management experience the company could bring to the new entity.

Raising the necessary capital for the minimum equity requirement and the cost of the vehicle procurement forced most of the bidding companies to forge partnerships. The City of Bogotá never offered any municipal guarantees for bank loans for vehicle procurement, so securing the necessary financing was a big concern of the transporter companies. The only thing that Bogotá offered the banks was a letter stipulating that if the municipality did not allow the fare to rise with the formula agreed to in the operating contract, the municipality would pay compensation into TransMilenio’s trust fund.

While some of the operators had relationships with banks from Brazil because they had bought Brazilian vehicles before, others were forced to look for partners with formal sector companies that had credit histories and relationships with the banks. In a couple of cases, outside investors approached affected owners and agreed to form a company together, and the outside investors had connections with banks. However, in Phase 1, it was actually not that easy to find investors from outside the bus industry willing to jump into the Bogotá bus business. Most vehicle operating companies that did so were from related industries (vehicle suppliers, trucking, etc.). Those that expressed interest wanted to find local bus operator partners not only to meet the tender requirements but also to run the business effectively.

The city worked with these consortia in approaching private banks. The banks were very reluctant to lend money to these transporters because the transporters were an informal economic group without a financial history. In the end, some of the final operating companies did secure financial support from private Colombian banks, and others from Brazilian banks such as BNDES, the Brazilian development bank and export credit agency, since the Brazilian banks were more familiar with BRT systems.

The problem of securing loans was also partially solved by the creation of a trust fund to collect the fare revenue. Banks have primary access to the fare revenue to repay the loan. Once this was established, it was a lot easier to convince banks to provide financing.

In Phase 1, fifty-eight of the sixty-four preexisting bus enterprises or collectives participated in the bidding process, and three of the four trunk operating companies were majority-owned and operated by former affiliated bus enterprises. The trunk companies were Si 99, Connexion Movil, Metrobus, and Expresso del Futuro.

Si 99 was formed from the largest independent affiliated bus enterprise. Its shareholding was 40 percent from one family, 15 percent from five other affiliated individuals who were friends of the family, 44 percent came from small individual owners, and a very small share went to RATP (1 percent), the French public transport operator. The main reason for the inclusion of RATP (the French commuter rail provider) was to secure from it some critical software used for scheduling, and to secure the additional points in the tender from having an international partner.

Together, this included twenty-four of the separate integrated bus enterprises and three cooperatives, as well as over six thousand individual small bus owners. In Phase 1 there was no restriction in the contract that prohibited the resale of shares, so the cooperatives sold their shares after only two years at a very high price.

Another Phase 1 operator was Ciudad Movil. Ciudad Movil is a subsidiary of Connexion Movil, which also owns a Phase 2 operating company also called Connexion Movil. Because Ciudad Movil decided to tender operations, the possibility of one company owning operators in different phases emerged, naturally to the benefit of the early adopters.

Some 40 percent of Connexion Movil’s shares were bought by a Colombian industrial conglomerate called Fanalca that also owns “Superpolo.” Superpolo is a bus body manufacturer that is a consortium between Marco Polo (Brazil) and Superior (Colombia) that has joint ventures now with Tata in India, with a bus factory in Changzhou, China, and in Monterrey, Mexico. Another 20 percent was owned by Connex, the French transport company that was later bought by Veolia Transport, a large international transport conglomerate. The remaining 40 percent was owned by the largest affiliated bus enterprises in Bogotá. As there was no restriction in Phase 1 on the resale of shares, Veolia has since bought some of the shares from the Colombian affiliated enterprises. Connexion Movil now owns not only Ciudad Movil, but also Connexcion Movil (the Phase 2 trunk operator), City Movil (a feeder operator), Transantiago in Santiago, and a bus operation in Cartagena. The link with the international company no doubt has played a role in the rapid expansion of this company’s international operations. It is this company that has an operating agreement with the Rea Vaya Phase 1A operator, as discussed later.

Express del Futuro, another Phase 1 trunk operator, was initially formed 100 percent from thirty-four traditional affiliated bus enterprises. Over time the company has achieved ISO 9001 (quality certification), ISO 14001 (environmental certification), and OHSAS 180001 (industrial safety certification). One of these was a contractually required target, but the others the company did on its own initiative. It bought over twenty vehicles initially purely with equity because the company could not initially get bank financing. As the company needed more capital, over the course of the first year it called for an open expression of interest and found private investors who negotiated a 33 percent stake in the ownership of the company. The outside investor was put in charge of managing negotiations with bus suppliers and the banks. In the end, a bank finally closed the loan on the basis of individual guarantees of the outside investors, and the bank also required primary access to the trust fund (where the fare revenue is deposited), in addition to requiring the contract with TransMilenio that ensured a basic income to the company. This eventually led to a 30 percent/70 percent debt to equity ratio, which left a good profit margin. By Phase 2 the company had no problem at all securing a loan for US$350 million from HSBC. It now also owns Tao, a Phase 2 feeder service provider.

The last Phase 1 trunk operator was Metrobus. Some 20 percent of the company was initially owned by the affiliated enterprises, and the remaining 80 percent came from a single outside investor that managed a big trucking company. Since there was no restriction in Phase 1 on the resale of stocks, over time the trucking company eventually bought out all but about 1 percent of the remaining shares.

All six of the Phase 1 feeder bus companies were composed entirely of former affiliated bus enterprises. As such, fifty-nine of the sixty-six affiliated bus enterprises bought into TransMilenio after Phase 1.

Three problems became apparent during Phase 1:

- The mayor (by this time, Mayor Antanas Mockus) was concerned that Phase 1 had not sufficiently encouraged shareholder participation by individual bus owners;

- The scrapping requirement was too low, so many vehicles relocated to parallel arterials, badly congesting and polluting these parallel roads and competing with TransMilenio services;

- The mayor had also become concerned about the equity ramifications of the consolidation of stocks after the companies began operations. Mockus did not want a situation where a company formerly composed of bus owners would be taken over by an international conglomerate.

These issues were addressed in Phase 2 as follows:

Having 25 percent or more of the shares owned by small individual bus owners gave the bidder more points in the tender. In Phase 2, the shares owned by the small bus owners could not be resold for the first five years in order to avoid a takeover by an international conglomerate.

Because of these requirements, the stock composition of the companies turned out as follows:

- Si 02: 25 percent small individual bus owners, 75 percent affiliated bus enterprises (largely the same people as Si 99);

- Transmasivo: 25 percent small individual bus owners, 75 percent from 20 traditional affiliated bus enterprises. So far it has not secured any contracts outside of Bogotá;

- Connexion Movil: 25 percent small individual bus owners, 10 percent the biggest affiliated bus enterprises, 40 percent Fanalca, and 25 percent Connex (Veolia).

Finding a management team was another reason that some companies, but not all, opened up the company to outside investors. Most vehicle operating companies recruited management mainly through the use of an employment agency. In other cases the bus companies were owned by large companies established a long time ago and they had management skills among their own companies. Si 99’s general manager, for instance, was the son of one of the largest bus enterprise owners in Colombia, previously working as a manager in the state oil company, and came back to run the family business. Other management people were hired from the trucking industry.

Most of the people involved in the process now feel that it might have been better if the small owners and collective bus drivers would have been given “preferred” stock. This would have given them priority in terms of the payout of dividends and liquidation, and it would have inhibited the buyout of their shares, but removed their voting rights. The membership of the board should be constituted of transport professionals rather than ownership-based. Shareholders would be welcome in the general assembly but should not be part of the board.

The City of Bogotá also financed the construction of depots and offices for the operators, one for each of the trunk bus operators. Since the depots were owned by the city, this gave the city some control over the operator, as the BRT authority could have its employees in the depot monitoring vehicle departures, maintenance, and so on.

16.6.2VOC Formation in Mexico City

In the case of Mexico City, the city dictated both the stock ownership structure of the new company and the management structure of the new company. Both turned out to be imperfect and had to be modified later.

In order to avoid disputes among the members of the Ruta 2 Insurgentes association, the city decided, in dialogue with Ruta 2 Insurgentes, on the stock ownership structure of the new company. Not 100 percent of all the Ruta 2 drivers were impacted even on Insurgentes, so the Mexico City administration first determined which buses were impacted. If the bus route only overlapped the corridor for less than 50 percent of the route, it was not pulled out of operation and the operator was unaffected.

Secondly, as a condition for signing the operating contract with the newly constituted company, CISA (see “Company formation” below) required that the current operators turn over all of the affected vehicles for scrapping by the city. This scrapping requirement was directly related to the capital composition of the new company.

The city required some starting capital, approximately 15 percent of the cost of the vehicles. This worked out to be about US$10,000 per vehicle in cash that the operators needed to raise. In addition, they had to turn over their vehicles for scrap. They received US$7,500 for each vehicle scrapped as a scrapping allowance from the city. This, together with the US$10,000 per vehicle of cash investment, constituted roughly the 15 percent starting capital they were required to raise. This did not include any working capital, so they later regretted this decision and wished that they had required more starting capital. This company strongly recommended that in the future phases the starting capital be set at a level sufficient to cover all start-up costs or there will be serious financial instability in the opening period of the company. The company was profitable with this number of shareholders.

The government initially secured a loan from HSBC to cover the remainder of the vehicle procurement cost, and CISA had to accept this loan, as it was guaranteed by preferential access to the trust fund where the fare box revenue is deposited. The interest, at 14.5 percent, was pretty high. CISA eventually found a local bank willing to refinance at 11.5 percent, which significantly lowered its operating costs and increased its profits.

The municipal government of Mexico City dictated to Ruta 2 Insurgentes that the stock composition of the new company was going to be one share of stock for one vehicle turned over to the city for scrap. There were 262 buses that operated in the corridor that needed to be removed, and these were owned by 180 shareholders. There was a law in Mexico City that a bus owner could only own five vehicles, so the number of shares per owner ranged from one to five. Thus, the total number of shares was 262, divided proportionally among 180 shareholders.

The selection of the management team of the company was fairly straightforward. The general manager of the Ruta 2 Insurgentes association was considered to be a good manager and was therefore unanimously elected to be the new general manager. He knew he would not be able to manage all the functions of a modern bus company, however, so he quickly hired an outside expert, a transport professional and university professor, who became the operations manager. The operations manager in turn brought in several other people capable of optimizing maintenance regimens for big fleets, managing large numbers of personnel, training, and other management needs.

CISA took about two years to establish good maintenance regimens, scheduling, and labor practices. The company believes that an international partner might have reduced this learning curve substantially. However, now it is providing consulting services to Phase 2 BRT companies, non-BRT bus operations in Mexico City, and bus operating companies in other cities in Mexico.

In Phase 3 Metrobús, an intercity bus operator, offered to give shares in the parent company to all the affected owners in exchange for allowing them to take over the operating contract. In this way, the bus owners got shares in a more powerful national company and not just shares in a specially created entity. This is a model that could be further explored in other venues.

16.6.3VOC Formation in Jakarta, Indonesia

In Jakarta, there were four major bus leasing companies operating on the Phase 1 corridor. One of these was a national government owned bus company, PPD. Three of them were bus leasing companies. These companies were not fully transparent corporations meeting ISO corporate governance standards, but they did have bylaws, corporate identities, stockholders, and working capital. These bus companies owned fleets of vehicles and they controlled all the route licenses. These route licenses were not very cleanly registered but most had some sort of route license.

The governor of Jakarta decided to create a BRT company mostly out of the impacted operators. He had been to Bogotá and understood the process there. The company he created was called PT Jet. It had only one month prior to the start of operations. The governor forced these four impacted companies to join with a fifth company that operated taxis in the corridor. The reasoning behind adding the automobile taxi company to the consortium was that the governor believed the taxi company was well managed and also somewhat affected by the new service. These five companies were forced by the governor to become a consortium. The shares of the new consortium were divided roughly based on the number of vehicles operating on routes that overlapped more than 50 percent with the Phase 1 corridor, and the share of the new company, Ratax, was negotiated from this. The share structure is not very transparent. Jakarta did not require the old vehicles to be scrapped. Because these parent companies already had working capital, and were already corporations, they simply divided up the shares among the parent companies based roughly on the share of affected routes, and these parent companies remained the owner of PT Jet, the new consortium. The negotiations were quite easy because they were headed by the heads of the impacted companies.

PT Jet was not undercapitalized, but the company had numerous problems in the beginning because it had no experience operating an integrated bus company, as it was leasing companies and not operating companies. International technical advisers were donated to the companies to develop scheduling protocols and personnel protocols but much of this type of information is proprietary so the technical support was not entirely successful. The company did not operate particularly well, though the problems were mostly sorted out over the first several years of operation. Jakarta also did not supply the operator with a fully equipped depot, which may have contributed to poor vehicle maintenance.

In Phase 3, TransJakarta tendered out operations for some 40 percent of the service. The company formed of the 60 percent was a former affected collective with weak corporate governance and high operating costs. The quality of service was quite low and the cost per kilometer was high. The tendered part of the service was contracted out to a private intercity bus operator that was a modern bus company with no ownership from affected owners. The government argued that as the government paid 40 percent of the total capital investment (inclusive of vehicle procurement) it had the right to tender out 40 percent of the market. The service provided by the outside operator tended to be better than the service provided by the impacted bus owners.

16.6.4VOC Formation in Johannesburg

In Johannesburg, the creation of the vehicle operating companies from affected minibus taxi operators was done through negotiation with affected owners without any element of competitive tendering, which in turn required a more interventionist approach to company formation on the part of the CoJ.

Because the negotiations with impacted owners had not concluded by the time operations needed to start (to provide service for the 2010 World Cup), the city needed to buy the vehicles on behalf of the future VOC, and find an interim operator. The financial adviser hired to finance the vehicle procurement (HSBC) set up a temporary company that owned the vehicles and was responsible for repaying the loan. This “paper” company service was essentially run by the department of transportation of the CoJ. The loan by HSBC to the paper company was guaranteed by the CoJ. This temporary company created by the CoJ started using many of the impacted drivers, but it supplemented this with former and current Metrobus (the Johannesburg municipal bus operator) management. This company operated the Rea Vaya BRT system until the negotiations with the affected taxi owners could be concluded.

Because the impacted owners in Johannesburg were being formed into one company from nine often competitive separate minibus taxi associations, and it was difficult for these associations to come to agreement on a shareholding structure for the new operating company, the CoJ ultimately had to dictate the basis of stock ownership in the new company. The taxi negotiating committee itself, after many months, had made little progress on its own and did not object to the CoJ dictating the shareholding structure, largely as a way of avoiding internal acrimony.

The CoJ decided on the following process to becoming a shareholder. First, it decided that the total number of shares in the new company would be 575, representing one share for each minibus taxi that needed to be withdrawn from service and turned over for scrap or resale to a CoJ-appointed leasing company. Shares could not be based on route licenses because the route licensing was so poorly organized.

The CoJ, based on impact area, determined the allocation of vehicles that needed to be removed per association, and shares per association as in the table below. In this way, shares would be divided up among the associations in proportion to the number of routes that were affected. The associations were not, however, formally recognized as parties to the negotiation.

Table 16.4Distribution of Shares in the Vehicle Operating Company by Taxi Association Affiliation

| Taxi Owners Belonging to the Following Taxi Associations | Distribution of shares in the VOC |

|---|---|

| Soweto Taxi Services (STS) | 180 |

| Witwatersrand African Taxi Association/Johannesburg Taxi Association (WATA/JTA) | 129 |

| Nancefield-Dube-West Street Taxi Association (Nanduwe) | 77 |

| Meadowlands Dube Noord Street Taxi Association (MDN) | 90 |

| Diepmeadow City Taxi Owners Association | 59 |

| Bara City Taxi Association | 13 |

| Noordgesig Taxi Association | 9 |

| Dobsonville Roodepoort Leratong Johannesburg Taxi Association (Dorljota) | 7 |

| Faraday Taxi Association | 6 |

| Johannesburg Southern Suburbs Taxi Association (JSSTA) | 5 |

| Total | 575 |

When the owner registered as an affected owner (described above) the operator was given a verification document authorizing them to do one of two things:

They can opt to become a shareholder in the new VOC, in exchange for which, they have to turn over to the CoJ this verification document along with at least one valid operating license and all the vehicles they wish to turn in. They would be given one share per vehicle turned in.

Alternatively, parties may opt out of the BRT system. The initial thought was that those choosing not to be part of the BRT company for whatever reason would be able to use the verification document to receive a new, enforceable route license under a new regulatory regime established under the CoJ. In the end, while the CoJ closed the most important taxi ranks (daladala parks) and scrapped 575 vehicles, some taxi operators who chose to opt out continue to operate along all or part of the BRT corridor, eroding the customer base of Rea Vaya. Previously, route licensing was under the provincial government, where it was poorly managed. New legislation gave the power to the city, but this power was only gradually taken over by the city. As a result, the CoJ had yet to develop the power to regulate the competing routes other than through the closing of taxi ranks.

With the help of technical advisers of their choosing, paid for by the city, impacted owners wishing to become shareholders in the Rea Vaya operating company formed “taxi operator investment companies,” or TOICs, one for each of the nine taxi associations to which the owners belonged. Owners were entitled to buy one share in a TOIC for each taxi they took off the Phase 1A routes. They also had to cancel its operating license. Each had to invest US$5,157 per share (converted from R54,000 with a January 2014 rate on XE.com) held into the company equity, which is the amount of money the government pays for the scrapping of old taxis. More valuable vehicles were sold by the company hired by the city to handle the turnover of vehicles.

After the negotiations were concluded with the impacted operators, the temporary company set up by the city to run the services was then sold to the nine TOICs, who designated thirteen nonexecutive directors to the company’s board, appointed one of the taxi leaders in the negotiations, Sicelo Mabaso, as chairperson, and renamed it “Piotrans.” This was to reflect, in their words, “the pioneering steps of the taxi operators who have decided to transform and grow into the fully fledged public transport operator as part of the public transport transformation process in the city and South Africa.”

In other words, the company inherited by the taxi owners was already a going concern with seventeen months of operations before the affected minibus taxi owners took over the ownership. Staff were already employed, including a full complement of drivers drawn from the taxi industry and trained by Scania to drive the vehicles. A three-year maintenance agreement for the vehicles was in place with Scania. A depot built and owned by the city was in operation with a fuel-supply contract. The 143 vehicles had been procured by the city on behalf of the company, the financing had been arranged, and while the company was responsible for repaying the loans to the Brazilian ECA, the City of Johannesburg stood ultimately as responsible for their repayment.

There was a six-month period during which handover from the management of the temporary company to the new board and management occurred. In this time, the city provided an in-depth orientation and capacitation program for the new board of directors and mentoring for the new management team. Penalties for nonperformance in the operating contract were only introduced after an initial grace period.

The CoJ required, as a contract condition, that the new company enter into a management contract with “a suitably experienced bus operating contractor and/or key management personnel.” Fanalca, the large Colombian industrial group, was announced in early 2010 by the taxi leadership as its choice of experienced bus operating contractor. Fanalca, among other operations, has BRT operating companies running 5,000 vehicles in South America. It operates BRT as part of TransMilenio (Bogotá), Transantiago (Chile), Metrobus (Panamá), MIO (Cali), MetroSinú (Montería), and SITP (Bogotá). It subsequently established Fanalca South Africa as a local subsidiary.

The understanding from the outset was that it would be both a management and an equity partner. The city thus agreed to amend the bus contract to allow the shareholders (TOICs) to sell a maximum of 24.9 percent of the shares to a suitably experienced BRT operator approved by the city, no sooner than a year after the signature date. The proceeds from selling the shares could only be used for the purpose of capital expenditure and/or working capital for the bus company. The nine TOICs and Fanalca entered into a heads of agreement, outlining the management and operational support which Fanalca would provide to Piotrans, and that discussions leading to Fanalca acquiring the allotted shares in the company and becoming a co-owner with the TOICs would take place a year from inception of operations.

Sicelo Mabaso, the chairman of the Piotrans board, said the decision to partner with Fanalca was done to ensure the success of the company. He said, “This is a totally new project, and we need to deliver a professional service. We looked locally and found no one, so we had to look at successful BRT systems.” Regarding the proposed sale of shares to Fanalca, he added: “We are looking for sustainability and we felt the best way of ensuring success was by providing them with an interest and stake in the company.”

The management team announced by the new directors on February 1, 2011, named Victor Cordoba of Fanalca South Africa as the inaugural CEO. Taxi leaders from the negotiations were placed in the roles of deputy CEO and corporate affairs director. The chief financial officer from the temporary company stayed on, as did the majority of incumbent staff, and roles such as human resources and company secretary were filled by South Africans. However, Fanalca supplied a significant number of full-time and part-time personnel to the operation. Fanalca estimated that at any one time, it had up to ten of its staff in Johannesburg working with Piotrans. This included its engineers in the minimum three positions in terms of the heads of agreement, namely the CEO, technical manager, and operations manager, supplemented with three other full-time engineers in the roles of a second operations manager, deputy chief financial officer, and driver trainer. Only costs for the three full-time positions were covered by Piotrans, and Fanalca did not charge any management fee or the costs of other personnel seconded to the operation, nor share in any profits.

Over the fifteen months from takeover, Piotrans has improved on many aspects of the service compared to the performance of the temporary company. For example, by May 2012, levels of absenteeism, breakdowns, accidents, maintenance costs, and dead kilometers were all significantly reduced. The number of vehicles washed per day doubled and 99.86 percent of scheduled kilometers were being operated.

In February 2012, a year had elapsed from the launch of Piotrans, opening the way for the sale of shares to Fanalca. However, it began to emerge that there was dissension within the Piotrans board. Various TOIC directors were by many accounts reluctant to sell shares to Fanalca, preferring that ownership of Piotrans should remain with the original shareholders. Others were in favor of honoring the heads of agreement, and selling the allotted 24.9 percent shareholding to Fanalca. The board agreed to follow a negotiation process with timeframes and appointed a negotiation team, but little happened. In Fanalca’s perception, there were continuous failures by the board to move forward with this process, or to make progress with producing the proposed transaction document. By mid-May, this had created serious doubt for Fanalca about whether its huge commitment was reciprocated, and whether a long-term relationship with the TOICs was feasible. It took the view that it had no interest or intention of forcing its participation in Piotrans if the TOICs did not wish to pursue a partnership. In their view, this would create instability, which would be bad for the company, the system, and the customers.

On June 7, Fanalca formally withdrew from any further participation in Piotrans, at both a management and potential partnership level, and terminated its staff services formally from June 13. To avoid a negative impact on customers, Fanalca developed a transition plan and made its technical team available for eight further weeks to hand over the full operation of Piotrans to the TOICS and local staff.

The chair of the board, M. K. Mohlala, who replaced the late Sicelo Mabaso, says that Fanalca decided to withdraw before matters were resolved. He says the talks did not get off the ground because Fanalca pulled out.

Restructuring then took place. A new key position of chief operating officer has been created to oversee the operations and technical functions, and lightening the concerns of many is the news that this will be filled by Javier Cajiao, the former technical manager supplied by Fanalca who has signed a five-year contract with Piotrans from September 1. The technical manager position—for fleet maintenance and in charge of the workshops—has been advertised, while the operations manager position will be taken by Eric Motshwane, the former corporate affairs director and key taxi leader in the negotiations. He was specifically trained and mentored by Fanalca over the past year to assume this role. Mohlala, the chairperson of the board, who will act as CEO for the time being, is confident that service levels will not be compromised. He says, “The skills are replaceable,” and adds that a great deal of skills transfer to local staff, reinforced in the two-month handover period, took place. The plan was always for Fanalca to hand over to local management and staff, he adds. He says that Fanalca’s technical and operational expertise, the people they sent, and their attention to detail had “overjoyed” him, and that they had transferred a lot of skills to the people they worked with closely.

Among the difficult gaps to fill may be the plan to replace the outsourced maintenance contract with full in-house maintenance. Fanalca had projected to cut overall maintenance costs by 26 percent by doing this. Another is the crew scheduling function where the company will need to purchase software to replace that previously supplied by Fanalca and train staff to use it. In the meantime, the city’s Rea Vaya staff will assist Piotrans with this function and the software.

16.6.5VOC Formation in Lagos

In the case of the Lagos busway system, the new franchise company, FBC, formed by officials and operators from the informal minibus sector, put in place a management team, with some outsourced functions, and recruited drivers (called “pilots”) from their informal operations. However, its inexperienced team proved inadequate to the task of managing a controlled and scheduled operation, particularly when the fleet grew rapidly from 100 to 260. The Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA) stepped in and provided relevant expertise to the inexperienced company in the form of a specialist from one of the major private sector bus and coach operators in Nigeria. It also required the outsourcing of vehicle maintenance, financial management, and operational management, including all human resource issues. LAMATA also stepped in and divided the fleet and drivers into four units of fifty-five vehicles, each with its own operational manager recruited by LAMATA, and a fifth carrying out scheduling. FBC plans to understudy and replace the functions provided by LAMATA recruits or outsourced contractor, but this will take a considerable time (Integrated Transport Planning Ltd., 2009; and Mobereola, D., 2009).