12.4Alternative Institutional Structures for BRT System Management

To punish me for my contempt for authority, fate made me an authority myself.Albert Einstein, physicist, 1879–1955

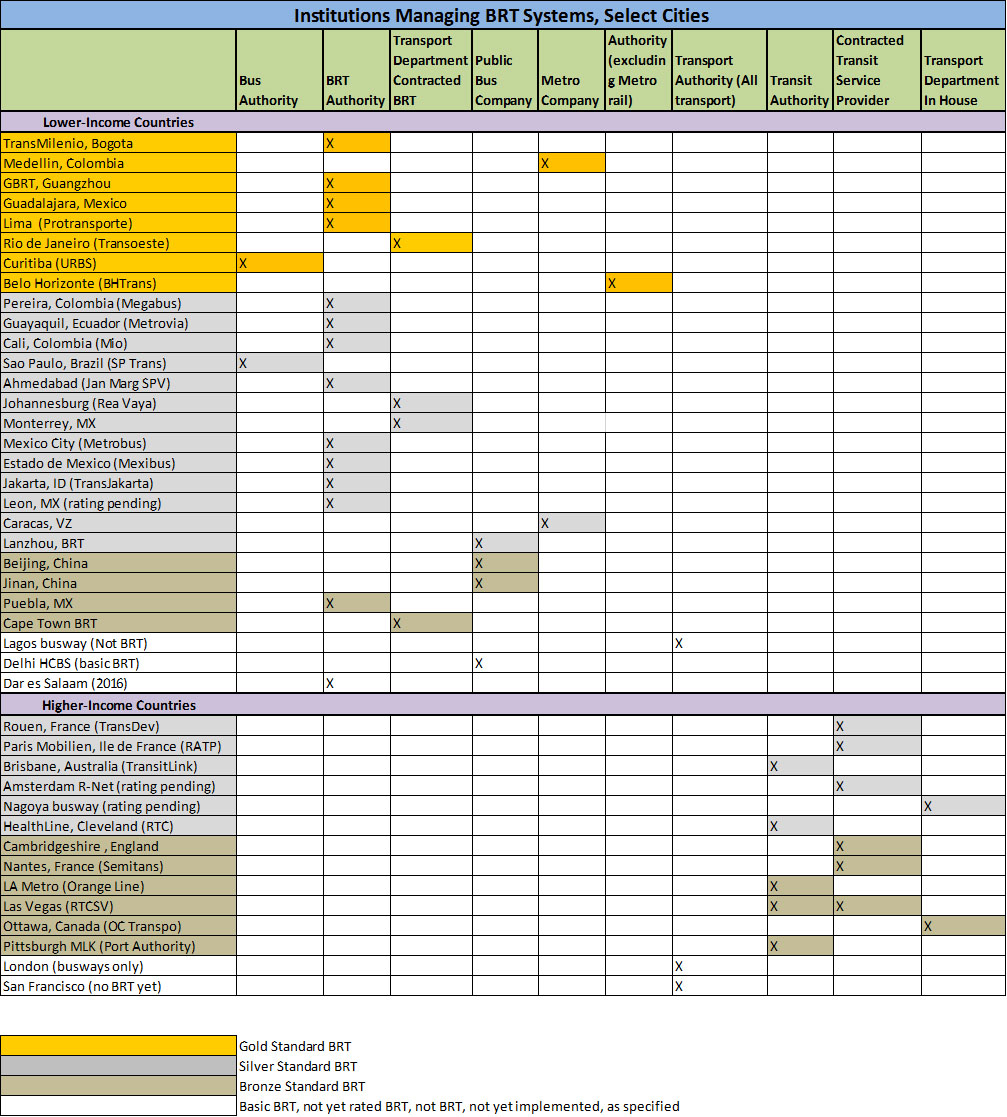

While urban transportation systems are managed in a variety of ways in different cities, successful BRT systems tend to exhibit certain characteristics and organizational forms. Figure 12.3 provides a reasonable sample of the better BRT systems and their associated institutional forms.

The types of institutions responsible for managing BRT systems vary greatly between higher- and lower-income economies. In lower-income economies, the majority of BRT systems are managed by public authorities with responsibilities solely focused on the BRT system. A few are managed by public authorities with responsibilities for managing both BRT routes and normal bus routes. A couple are managed by public metro companies. A few are managed by public bus monopolies. The South African systems are managed by multiple divisions inside municipal departments of transportation, but they are contracted out in a manner similar to how a Latin American BRT authority would contract out operations.

In higher-income economies, the trend is for public transport authorities to operate BRT systems in addition to standard bus and rail operations, or to contract out all public transport services (not only BRT) to a public transport service provider that is likely to have mixed public and private ownership. A few systems are directly operated by a government department.

12.4.1BRT System Administration in Lower-Income Economies

12.4.1.1BRT Authorities

The majority of the best BRT systems in lower-income economies are managed by public authorities or companies with a mandate focused solely on managing the BRT system. These authorities are often similar in structure and purpose to metro companies. Decision makers looked at how successful metro projects were managed, and they noticed that most of them were run by specialized corporatized agencies or government companies specifically focused on building and operating the metro system. They wanted BRT systems to enjoy the same management benefits as metro companies. However, they were also able to explore other contracting forms, such as having multiple, separate vehicle operators operating on the same trunk infrastructure, which have proved more difficult to implement in rail systems.

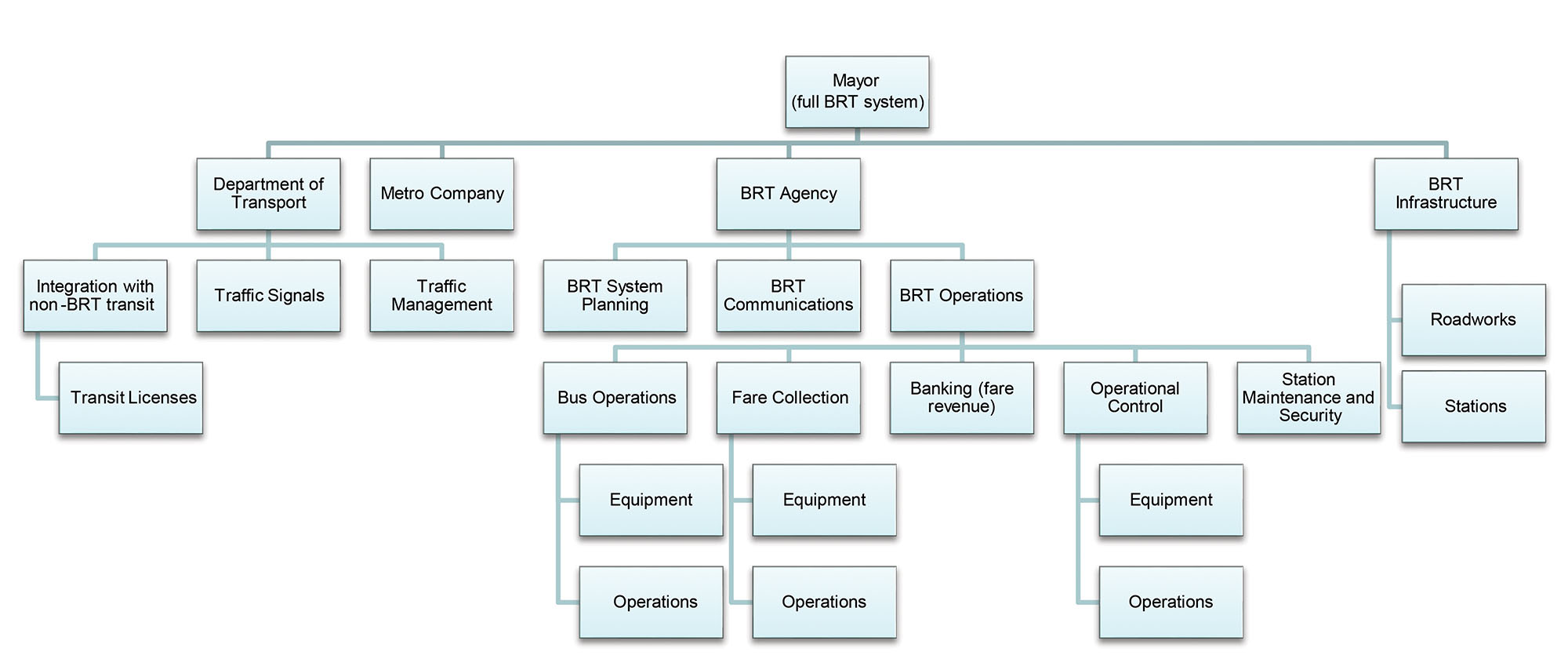

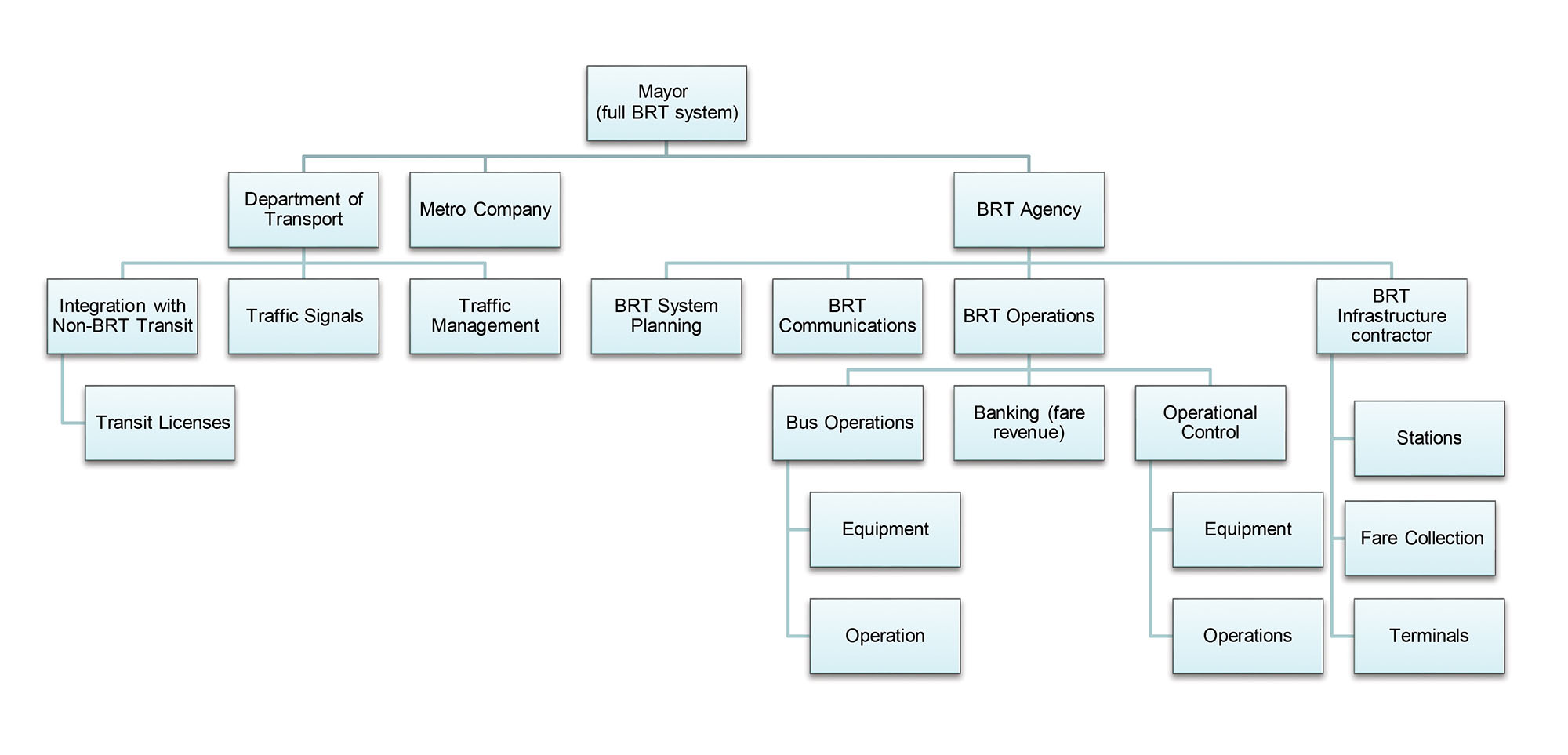

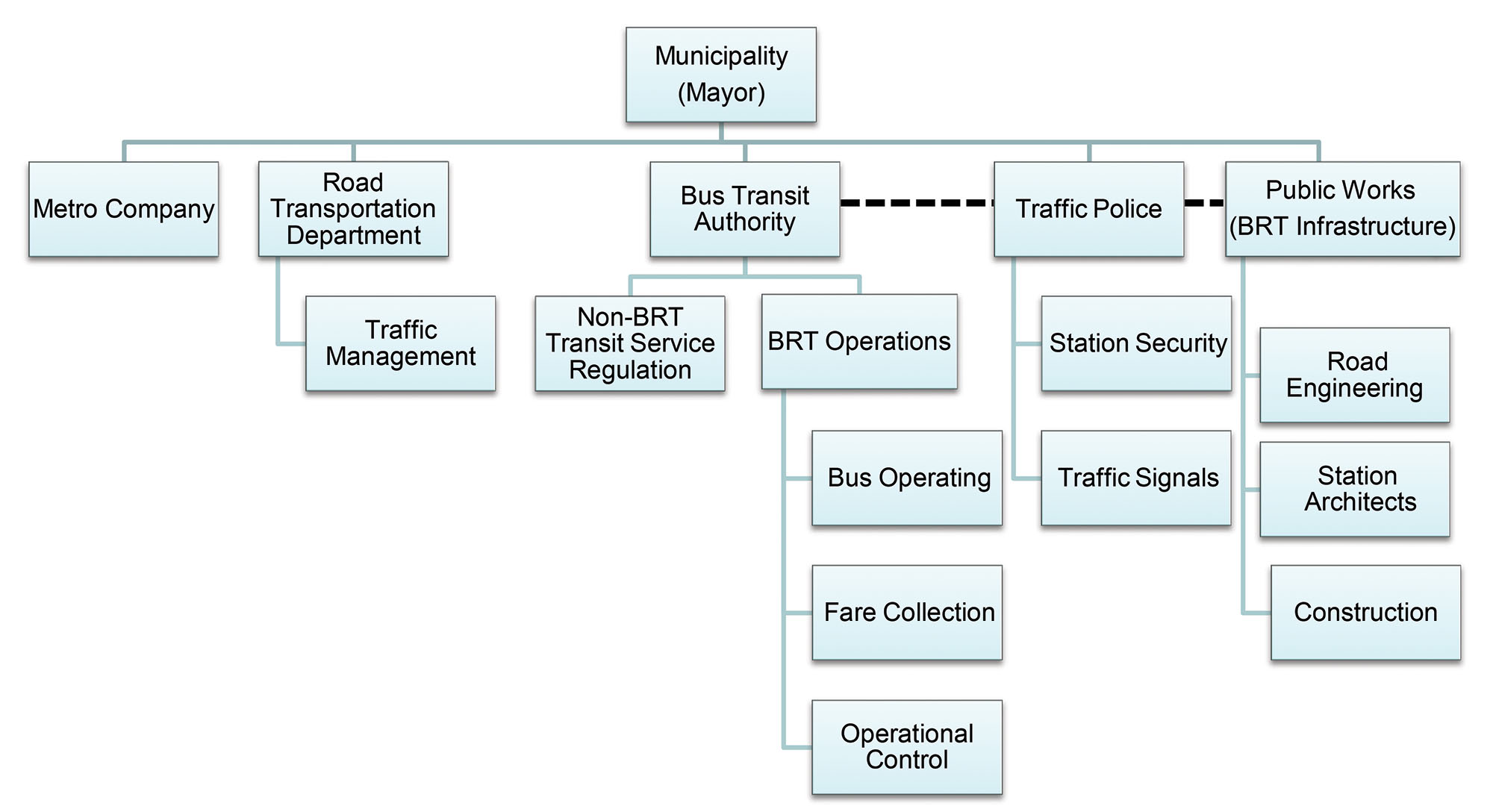

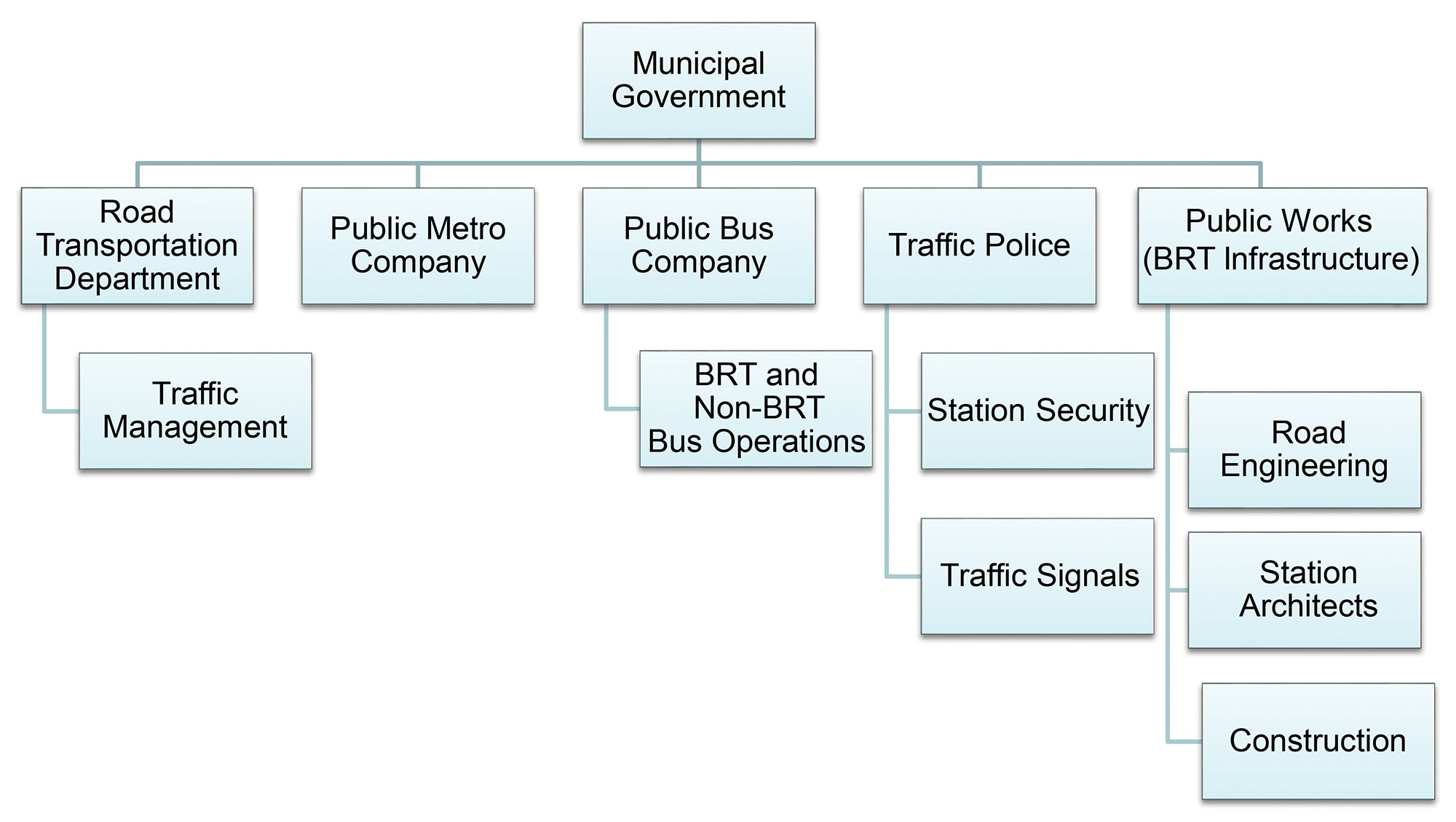

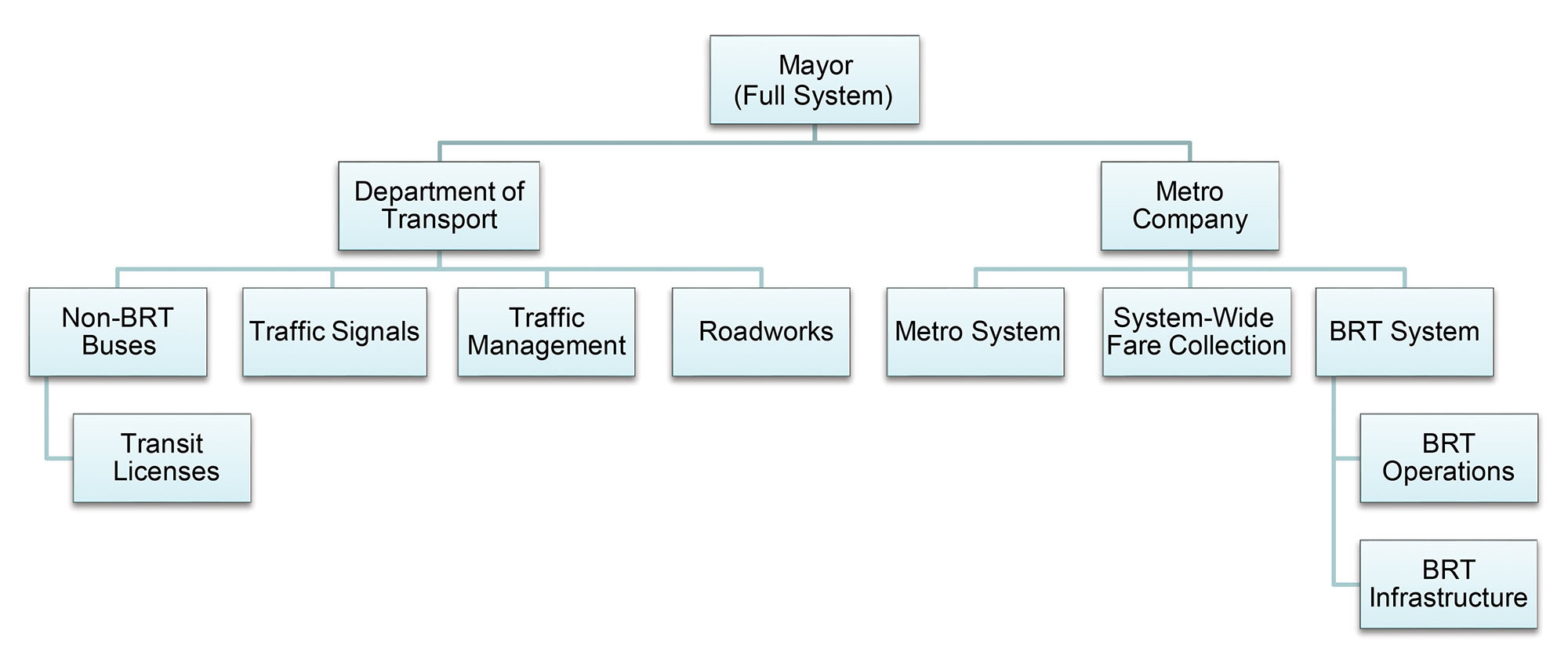

Figure 12.4 depicts a fairly typical administrative structure for a BRT system managed primarily by a BRT authority. The BRT authority manages the vehicle operations (usually through subcontractors), the fare collection system, the operational control systems, the system communications, and the customer information. The BRT authority is also given oversight of the design and construction of all BRT infrastructure. They are not generally responsible for directly contracting out the necessary civil works, however. Contracting out large civil works is a specialized skill that is generally better managed by an entity that already has experience managing civil works contracts worth tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars. Though this is generally managed by a department of public works or its equivalent, the designs need to be approved by the BRT authority before they can be tendered. This approval role is best written into the BRT agency’s bylaws and confirmed by interagency agreements. If this is impossible, the mayor or another key decision maker will need to support the decisions of the BRT authority leadership in frequent interagency meetings, where final approval over the design by the BRT authority is not fully formalized.

Similarly, responsibility for traffic markings, designation of the dedicated lanes, traffic signals, and the licensing and regulation of non-BRT public transport operations on the BRT corridor, generally remains with the city or national department of transportation. Again, if the BRT authority needs traffic signals changed, or non-BRT public transport licenses changed, the key decision makers will need to back up the BRT authority or else the quality of the system will be compromised. Police or traffic departments that refuse to follow proposed turning restrictions or signal phasing proposed by the BRT authority can cause operational problems for the BRT system and worse mixed-traffic congestion.

Metro companies are typically separate management entities. Coordination of the physical design and fare systems of the BRT with the metro depends on the BRT authority designing the system with good physical integration and fare system compatibility with an existing metro system. If the metro system is new and the BRT already exists, it is incumbent on the metro authority to design its new system with integration with the BRT. The mayor or senior decision makers need to require this.

Normally, BRT authorities are public entities governed by a board of directors, and in this way they differ from normal government departments. The board of directors generally gives the management of the BRT authority an arms-length relationship to the heads of government. The board is likely to be appointed by the mayor, or in the case of an agency funded by both state and local government, by the state and local government. An appropriate composition might include a high-level city representative, a representative from both the local and state governments, and two further representatives from academic institutions or technical experts in the field. Though it sometimes occurs, it is generally not advisable to include private transporters (e.g., vehicle operators) or unions directly on the board as this is likely to lead to conflicts of interest, since public transport operators and unions are likely to end up on the other side of the negotiating table from the BRT authority’s management. Ideally, board positions would be rotated with overlapping tenures to ensure continuity and minimize the impact of political changes. The general manager of the BRT agency should be chosen by the board for fixed periods of at least three years, subject to extension.

TransMilenio SA was formed as a BRT authority that reports to the city’s mayor through a board of directors. Other more traditional government departments also play a significant role in Bogotá’s BRT system, but the new BRT authority has taken the lead in terms of ensuring efficiency and an entrepreneurial approach. TransMilenio’s board consists of ten directors who are derived from a cross-sectional representation of interested parties. The city’s mayor or a representative of the mayor acts as the board’s chairperson. Included in the board are NGOs and citizens’ groups who are better able to provide a customer perspective. Many of the related agencies, such as the transport regulator and the public works agency, are also represented on the board in order to assure coordination between all government organizations. In summary, the groups and individuals included in the TransMilenio board of directors are:

- Mayor of Bogotá;

- Secretariat of Transit and Transport (transport regulator);

- Institute for Urban Development (IDU);

- Civil society representative (from academia or elsewhere);

- Civil society representative (from transport or environmental NGO);

- Municipal Department of Planning;

- National Department of Planning;

- Municipal Secretariat of Finance.

In the early years of TransMilenio, the board did not include the Department of Transportation. It was only added later, after TransMilenio was well established.

Board meetings are also attended by the general manager and assistant general manager of TransMilenio SA. The staff does not have a vote but is there to answer questions that may arise. The board of directors is also served by financial and accounting specialists who can handle audits of the system.

BRT authorities are generally established as independent public authorities or government companies for the same reasons that metro companies are set up this way. First, independent agencies and companies can be (though they are not always) established in a way that frees them from cumbersome civil service personnel policies. Such policies tend to make the hiring and firing of staff difficult; compromise the ability to pay competitive salaries for specialized skills; make the hiring of new staff a protracted affair; and politicize decision-making and hiring and firing procedures, leading to ineffective institutions, lack of customer responsiveness, and bloated payrolls.

The other reason specialized BRT authorities are established is that BRT systems are complicated to set up and operate, so they need a fully dedicated team managing them. If the team managing the project has other administrative tasks, or is constantly being diverted from the task of implementing the BRT project with other political objectives, then it is likely that the project will be delayed or badly implemented. Too frequently, the persons responsible for a BRT project have so many other administrative responsibilities that they are never able to focus on creating the new system. Over time, as the BRT project team learns their jobs, develops protocols for running the system, and the number of trained staff expands, it may become possible to expand the responsibilities of the BRT authority to the management of the remainder of the bus system.

Additionally, BRT system administration is generally easier to financially ring-fence when it is a stand-alone entity than when it is administratively under the same management as a rail system. This is because a BRT system in a lower-income economy is more likely to be able to fully recover the cost of the operations, including the cost of procuring the vehicle fleet, financing the vehicle fleet, and managing the system, than is a rail company. TransMilenio in Bogotá, for instance, funds the entirety of its operating contracts, the cost of its management staff (TransMilenio SA), the vehicle procurement, and the financing of the vehicle procurement from fare box revenue. This creates the possibility of insulating all of these functions from political interference in management, which becomes possible as soon as the management entity relies on the legislature for its budget allocation. A rail system, by contrast, is far less likely to be able to cover its operating costs, its rolling stock procurement and financing costs, and its own management costs out of fare revenues. By linking the two entities, it is likely that the BRT system will be financially encumbered by the losses of the rail division and lose the independence possible only from financial self-sufficiency.

The BRT authority initially is not generally in charge of managing the licensing and regulation of the remaining non-BRT public transport services. There are several reasons for this:

- Transportation departments of municipal governments tend to regulate informal bus and minibus operators in a way that earns both licit and illicit revenue for the department. As such, these departments’ revenue streams are threatened by the BRT projects, and hence they are sometimes bad advocates for BRT. Initially at least, it is sometimes safer to keep the BRT project team at arm’s length from these departments of transportation.

- It is a big job to regulate the non-BRT public transport operators in a city, and requiring a BRT authority to also be responsible for this task is likely to take talented administrators away from other more mission-critical tasks involved with implementing and operating the BRT system itself.

If the non-BRT routes are regulated not by the BRT authority but by an existing department of transportation, it is important that the BRT authority be given the authority to cancel or reroute any preexisting route licenses or service contracts where these services will be superseded by the new BRT service plan. If the BRT authority does not have the power to regulate the non-BRT public transport routes, it is possible that these routes will continue to operate in parallel with the BRT, contributing to mixed-traffic congestion in the corridor and draining the BRT system of customers. Forcing department of transportation heads to comply with this mandate has frequently proved difficult. For TransMilenio, Mayor Peñalosa had to fire several department of transportation heads in order to get the department to comply with TransMilenio’s order to reroute or suspend certain route licenses that were made redundant by TransMilenio. In Jakarta, coordination on non-BRT route licensing between TransJakarta and the Department of Transportation was a continuing source of tension. In Johannesburg, Cape Town, and many other BRT systems, it has proved very difficult to coordinate the BRT and non-BRT services.

Experiences with the quality of these independent BRT agencies varies greatly with circumstances and other considerations. TransMilenio’s relative independence and administrative skill was exceptional in the early years of its operation. Over time, however, it became clear that the institutional structure alone was insufficient to protect the system from mayors who were less politically vested in the system. After Mayors Peñalosa and Mockus were no longer in power, subsequent mayors were less interested in maintaining and improving the quality of service at TransMilenio. Operational problems went unresolved, overcrowding that could have been solved by operational adjustments and targeted investments was left unaddressed, and the once stellar reputation of TransMilenio, while still positive, was tarnished. Most of the other BRT systems in Colombia are modelled on TransMilenio and have performed reasonably well.

Metrobús in Mexico City, which was an independent BRT authority modelled after TransMilenio, did a reasonable job of emulating the management success of TransMilenio and has maintained a reasonably good level of service as new corridors have been added. Guayaquil’s BRT is run by a dedicated BRT authority. Guayaquil placed the BRT system under the control of a nonprofit quasi-governmental body, the Fundación Municipal de Transporte Massivo Urbano de Guayaquil, which has representation of a wider group of stakeholders on its board of directors and thus has slightly greater political independence. This works well in Ecuador to insulate certain critical institutions from political interference in a country where polarized politics tends to hamstring the management of other forms of public enterprise.

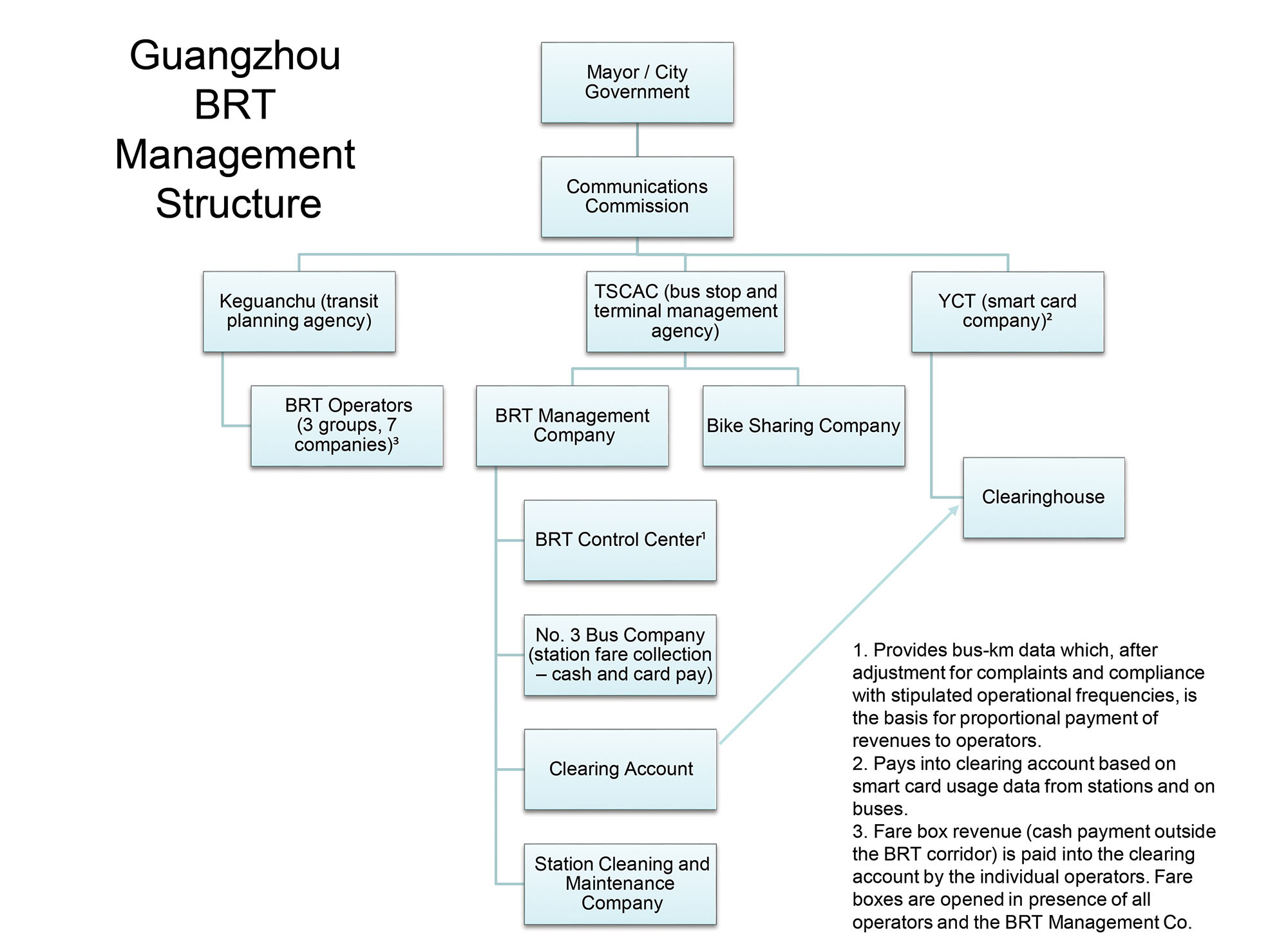

Guangzhou also created a public administrative body to manage the BRT known as the BRT Management Company. It is under the Bus Stop and Terminal Management Agency of the Communications Commission (Department of Transportation). It is not a public authority with an independent board of directors. It controls the fare collection system at the stations (via a subcontract with one of the BRT vehicle operators), the operational control center, and a station cleaning and maintenance company. The contracts with the three BRT vehicle operating companies, however, are not signed by them but by the Transit Management Bureau (Keguan Chu) that manages all the vehicle operating contracts in Guangzhou. The smart card fare collection contract is managed directly by the Communications Commission. The quality of service in Guangzhou’s BRT is generally considered to be better than in most of the rest of China, where BRT operations have generally been turned over to monopolistic municipal public bus companies. Guangzhou was an innovator in the contracting out of bus services to quasi-private companies (only a few of them were fully private, the others were companies owned by different branches of government) even before the BRT system was implemented, and these reforms were extended with the use of some basic quality of service contracting for the Guangzhou BRT, something that has made little headway in other Chinese cities.

In Mexico, in Puebla, and in the State of México, where part of the infrastructure is nominally going to be paid by the fare revenue, special purpose BRT authorities have issued contracts for both the infrastructure and the fare collection system in one contract and the vehicle operators in a separate contract.

In India, the creation of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) for administering a BRT project became a requirement for the receipt of national government public transport investment funds through the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) program. These SPVs are for the most part not as independent from municipal government as a public authority or a government-owned company typically is. They are mainly offices inside the office of the municipal commissioner and chaired by the municipal commissioner or deputy municipal commissioner. As such, BRTs in India have been funded by JNNURM while metro companies in India have been funded through “viability gap funding” administered by the ministry of finance for public–private partnership corporations. Though many of these SPVs were a far cry from the administrative competence of the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation, the Ahmedabad Jan Marg SPV (BRT Authority), however, was better than most. Though essentially an office of the municipal commissioner, it did successfully contract out the vehicle operations to private companies using quality of service contracts. Having an agency with an exclusive focus on managing the BRT system has thus generally been a reasonably successful strategy for managing a high-quality BRT system in a lower-income economy context.

However, it is insufficient to guarantee successful management. Other authorities with an exclusive focus on BRT have done less well. Normally, this has been because the BRT authority was never given the authority over all the key elements of a successful BRT system listed above. Governor Sutiyoso of Jakarta created TransJakarta, a BRT authority, when the BRT system first opened. Nominally modelled on TransMilenio, TransJakarta had few of the powers that TransMilenio had. TransJakarta did not sign contracts with the vehicle operators or collect the fare revenue: these functions were controlled by the Department of Transportation. Nor did it have control—or approval power—over the physical design. This was also controlled by the Department of Transportation. There were frequent disputes between TransJakarta staff and the Department of Transportation, all of which were won by the Department of Transportation because it controlled the budget, the contracts, and the fare revenue. How many of the design flaws and operational problems with TransJakarta were the result of the Department of Transportation’s control over key system elements in the early phases of implementation will never be known. Additionally, their concern about losing licensing revenues preempting their interest in designing a great BRT system will never be precisely known, but there is no question it was a significant factor. Over time, the powers of TransJakarta relative to the Department of Transportation have increased, but it is still too early to gauge the results of these transitions.

Though Delhi tried to create a BRT authority (SPV) to manage the high capacity bus system (HCBS) corridor, in the end it was never given the powers to properly regulate vehicle operations in the HCBS corridor, and it was also tasked with developing other potential public transport investments. Poor service, frequent vehicle breakdowns, flaws in the initial design, and an inability to take control of the traffic signals all contributed to a negative public image of the system.

In summary, while the best BRT systems have tended to be managed by BRT authorities, it is critical that these authorities actually have the administrative powers, control over fare revenue, and staff capacity to fulfill their mandate to manage the BRT system.

12.4.1.2Bus Transit Authorities

Bus transit authorities are similar in structure to BRT authorities, except that their mandate and area of responsibility extends beyond the BRT system to the regulation and licensing of all non-BRT bus and minibus public transport in the city. This form of BRT system management is typical of the Brazilian BRT systems, and Colombian systems may evolve into this administrative form.

Such bus transit authorities have been fairly successful in Brazil, mainly because Brazilian cities went through a process of bus industry consolidation and corporatization earlier than most lower-income economies. In most Brazilian cities, large private companies divide up bus operation management responsibilities across individual zones of the city. Small, informal bus operators were already transformed into companies by the 1960s and 1970s.

In Curitiba, for example, the company URBS began in order to manage a simple fare-sharing mechanism between the bus operators. BRT required off-board fare collection. The public transport market in Curitiba was divided into zones, and initially each corridor was controlled by the bus company in charge of that zone. When off-board fare collection was introduced, and some bus routes began to pass between one zone of the city and another, a third party was required to collect the customer revenue and then divide it between the bus operators in a manner that was acceptable to both companies. URBS, now the bus transit authority of Curitiba, was initially set up only to serve this function. Over time, it grew to become a full BRT authority; as it built its administrative competence, it added non-BRT routes and different roles in urban planning and operations like deciding the location of kiosks and cafés in public spaces, operating paid public WCs, and occupying needed underground or aerial space for infrastructure installation.

In São Paulo, the municipal BRT corridor and the bus corridors that allow taxis are all controlled by the same bus operator, São Paulo Transporte (SPTrans), which controls the entire zone of the city. The fare revenue on both BRT and non-BRT corridors is collected by SPTrans, a municipal public bus authority. BRT corridors that connect São Paulo cities within the metropolitan region are controlled by a bus agency of the state government (EMTU), part of the State Secretary of Metropolitan Transportation, under which there are similar agencies that control São Paulo metro (Metro-SP) and commuter rail lines of São Paulo Metropolitan Train Company (CPTM).

TransMilenio is also evolving into an agency that not only regulates the BRT system but also a growing number of strategic public transport corridors. In other words, it is trying to use the same type of quality of service contracts it implemented on the BRT trunk corridors for non-BRT corridors.

In both the Brazilian and Colombian cases, the expansion of the BRT authority’s remit evolved over time. It is largely unheard of for a newly created agency to take over the administration of both a new BRT system and an existing bus system, mainly because it is administratively difficult to manage both tasks at once.

12.4.1.3Municipal Department of Transportation-Contracted BRT

In a few municipalities, most notably in South Africa and in the Cambridgeshire Guided Busway in the United Kingdom, municipal or county departments of transportation are contracted out BRT operations to private operators in a manner similar to the contract structures typical of the Latin American BRT systems. However, the contracts with the BRT operators were instead signed directly with the municipality rather than with a new BRT authority.

In South Africa, the contractual form of an independent public authority under the municipality does exist (a “Municipal Entity”), but the track record of these institutions has been somewhat negative as they have proved to be difficult to hold to account and not particularly well managed. As such, when the BRT systems opened in both Cape Town and Johannesburg, both cities decided not to create new municipal entities to manage the BRT systems. Some elements of the BRT project were put under three different municipal entities in Johannesburg, and none in Cape Town. Both cities tried, in different ways, to mimic some of the elements of the contractual structures typical of the Latin American BRT systems.

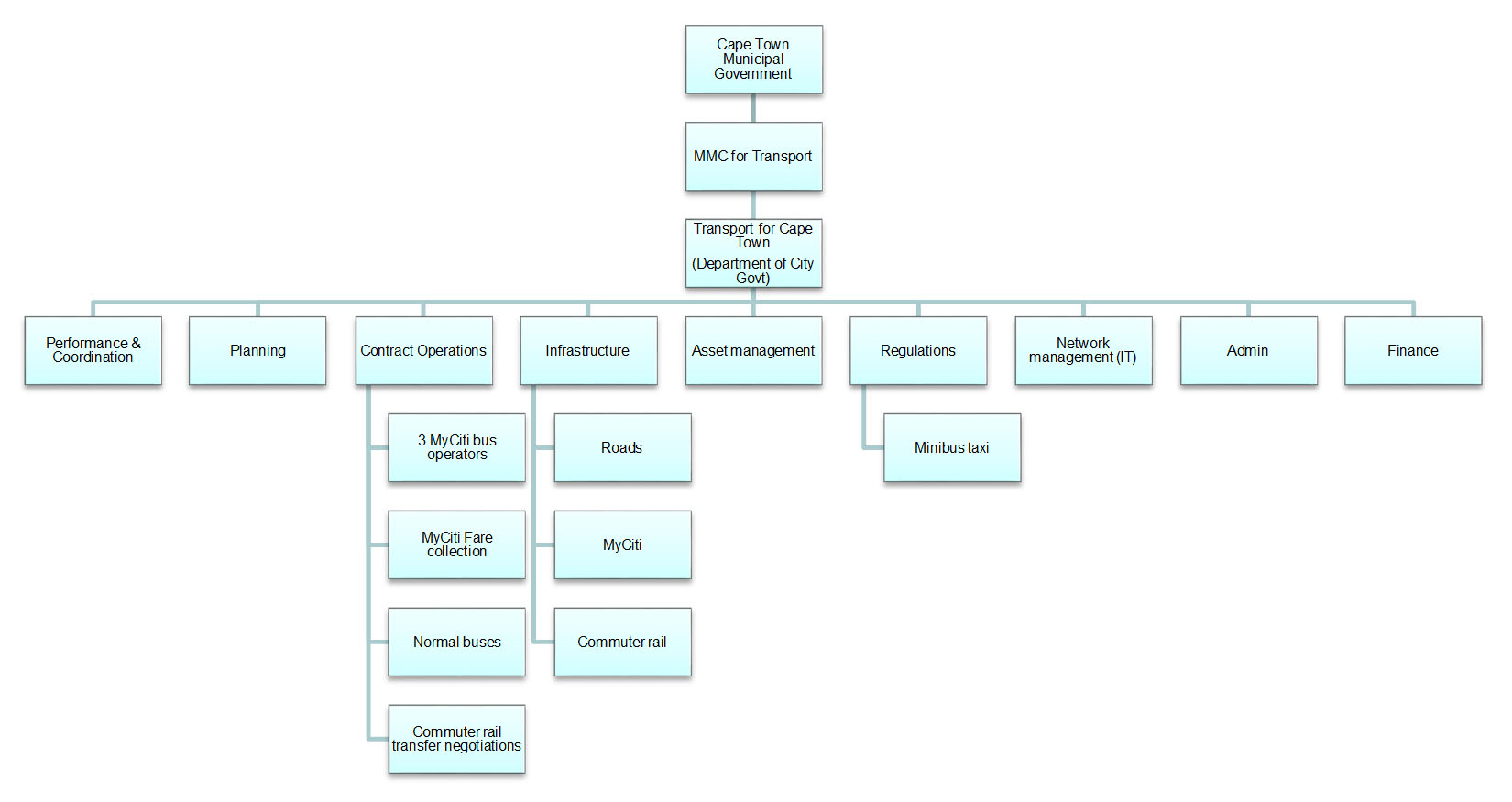

In the case of Cape Town, a recent restructuring has set up a quasi-transportation authority, called Transport for Cape Town (TCT) but inside a government department. The histogram below shows the structure of TCT.

TCT is a single large department of the city government that mainly reorganized the functions of the former transportation department. When the MyCiTi BRT system was first designed and became operational, there was a public transport unit inside the municipal department of transport. That unit’s only job was to design and implement the MyCiTi BRT system, because at that time other vehicle operations in the Western Cape Province were under the provincial government, though these services were in the process of being devolved down to municipal government control. The municipality had also not assumed control over commuter rail, which was still managed by PRASA (Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa), a national government agency. The public transport division had two divisions: infrastructure and operations. Most of the critical tasks related to the BRT system were managed by this office. After the restructuring, staff previously responsible for focusing exclusively on the BRT system are, as a result of this process of devolution, responsible for some additional tasks. The contracts department also manages contracts related to the takeover of the rail operations, the takeover of the vehicle operations, and other contracts. Though the name is modelled on Transport for London (TfL), TfL’s administrative structure is quite different. Rather than being a city department, TfL, and its main subsidiary, Transport Trading Limited (TTL), is a holding company for a number of largely independent subsidiary government companies such as London Bus Services Ltd. (which regulates and manages the buses), and London Underground Ltd. (which regulates and manages the metro system).

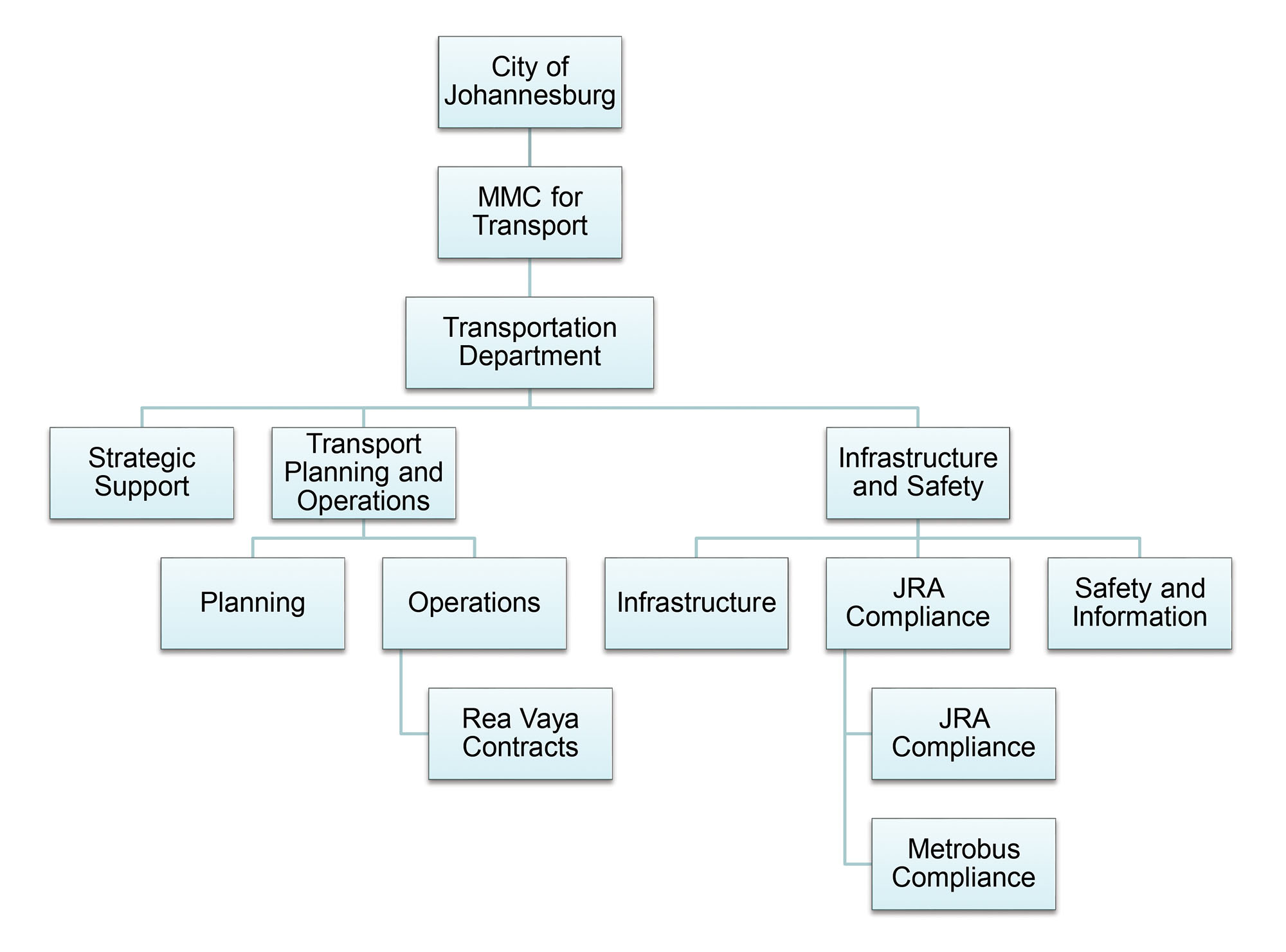

In the case of Johannesburg, the general structure of a BRT authority was also partially replicated inside a municipal government department. The BRT project office, Rea Vaya, had a dedicated staff and much of the attention of the executive director for transportation. Similarly to Cape Town, Johannesburg had not fully assumed responsibility for managing private vehicle operations or minibus taxi regulation or the local commuter rail lines. Johannesburg, unlike Cape Town, also operated a municipal bus company, Metrobus. As devolution proceeded, the executive director for transport had to take on other responsibilities as well. The histogram below shows how Rea Vaya was restructured. Rea Vaya no longer has any independent identity as an administrative unit. Earlier problems with the JRA and its contractors not being responsive to the needs of the Rea Vaya system were partially mitigated by putting it under the supervision of a special unit in the Transportation Department.

In both Cape Town and Johannesburg, the fare revenues are not strictly pledged to the BRT system. Both systems are currently operating at a loss. In both cities, staff have not been able to dedicate their full attention to the needs of the BRT system, and some operational problems have taken longer to resolve as a result. There have been issues with attracting and retaining talented staff, and of removing problematic staff, due to relatively modest municipal pay scales and civil service hiring and firing rules. To some degree this has been mitigated by bringing in long-term consultants to support the administrative staff.

12.4.1.4Public Bus Companies

In some cities, BRT services are managed by government-owned “public bus companies.” These government-owned companies differ from public authorities in that they only operate bus services, and they are generally structured like a company—but one that is owned by a government, usually a municipality. This administrative form was typical in many lower-income economies from the 1960s until the 1980s and most of them collapsed due to mismanagement. This administrative form survived, however, in a few countries, most notably China, India, and in a few places in Latin America. The legal vestiges of these companies still sometimes exist in other lower-income economies with rights that can cause problems for future BRT efforts.

In China, with the exception of Guangzhou, public bus companies are the norm. In the Chinese context, they offer an adequate quality of service, but are often resistant to change, and in general their performance as BRT operators is not strong. The BRT systems in Beijing, Jinan, and Lanzhou all have vehicle operations controlled by the public bus company. The vehicles and the quality of their service is of a similar standard of service to normal bus services. In India, many municipalities also continue to have public bus companies, though the Indian public bus companies do not generally manage BRT systems. The bus services managed by public bus companies in India vary in quality across the country, ranging from those with a reasonably good reputation (Bangalore, Mumbai), to those systems that nearly collapsed due to mismanagement (Ahmedabad’s AMTS, the public bus company that predated the BRT and continues to operate on some corridors in Ahmedabad). Most of the BRT systems in India are instead operated by special purpose vehicles (SPVs), as is the case in Ahmedabad and Indore. Delhi is the exception in which some of the HCBS buses are operated by the public bus company, but the sole responsibility for the poor quality of service does not rest on the public bus company as, in fact, there is no single entity responsible for managing the HCBS system. It has buses operated by both a public bus company (Delhi Transport Corporation, under the government of the National Capital Territory) and private individual operators with route licenses. Buses operated by the public bus company are generally considered to offer a better quality of service than private individual operators with route licenses. On Delhi’s HCBS BRT services, the DTC buses are more likely to have new buses and are somewhat better managed than the STA registered private buses but in other ways are operationally indistinguishable from other municipal bus services.

Metro-Company-Administered BRT Systems

In two cities surveyed, the operations of the BRT systems were managed by a publicly owned metro company: Monterrey, Mexico; and Caracas, Venezuela. The advantage of this structure is that it improves the chances of reasonable integration between the BRT services and the metro system services, both in terms of fare collection and physical infrastructure. The other advantage is that some metro companies, because of their relatively high cost, are able to afford reasonably qualified staff who can also be used to manage the BRT system.

The main downside of metro system administration is that any debts that might encumber the metro system will also end up encumbering the BRT system, so the possibilities of financially ring-fencing the system are less.

12.4.1.5Other Forms of BRT System Administration Observed in Emerging Economies

In Belo Horizonte, a public agency, BHTrans, is responsible for the management of the BRT corridors and other transportation services (conventional buses, taxis, etc.) within the city, including road transport and planning of non-motorized transportation. Regional bus services and the metro are under separate government authorities within the state government. This administrative structure has worked reasonably well to date.

In the case of Rio de Janeiro, the Municipal Department of Transportation (SMTR) supervises the service provided by a private BRT operator (Consórcio Operacional BRT Rio). This private enterprise is the result of an arrangement between the four consortiums that won the city conventional bus lines bid. SMTR is responsible for the BRT operational design and BRT Rio operates the system, provides vehicles, and maintains the stations’ infrastructure. This administrative structure is more typical in higher-income economies and will be discussed in greater depth there. In the specific case of Rio, it has limited the ability of SMTR to fully regulate the operating consortium, and the main problem has been significant overcrowding on the system that resulted from an insufficient fleet and the inability of SMTR to require additional fleet.

The Lagos busway, which did not meet the basic criteria to qualify as BRT, is supervised by a transportation authority with a very wide mandate but which in practice has yet to fulfill some areas of this mandate. It is further discussed in the next section on forms more typical of higher-income economies.

Conclusion: How and Why Lower-Income Economies Best Administer BRT Systems

In lower-income economies there is an emerging professional consensus that government institutions need to be built with the capacity to regulate and contract out BRT operations to qualified private operating companies. In most lower-income economies with either gold- or silver-rated BRT systems they are managed by special BRT-specific authorities. In countries with relatively weak municipal institutions it has proved easier and more effective to set up an authority focused specifically on managing the BRT system and only gradually widen the scope of this institution’s responsibilities. In countries like Brazil with a longer history of functional public authorities, these authorities often have a wider remit, but this emerged only gradually as the institutions developed the necessary administrative competence. In a few cases, even very good BRT systems have been operated by municipalities that have directly contracted private BRT operators without involving a public authority. What has not worked well in most cases is to have a BRT operated by a public bus company. Where these remain in lower-income economies, most notably in China and India, these institutions have not provided the best quality BRT services. Also relatively unheard of are large public authorities with responsibilities for all aspects of urban transport, ranging from BRT to metro rail to road traffic. Whatever the theoretical benefits of this institutional form, the institutional capacity to manage all of these functions in an integrated manner rarely exists in lower-income economies.

12.4.2Typical Administrative Forms in Higher-Income Economies

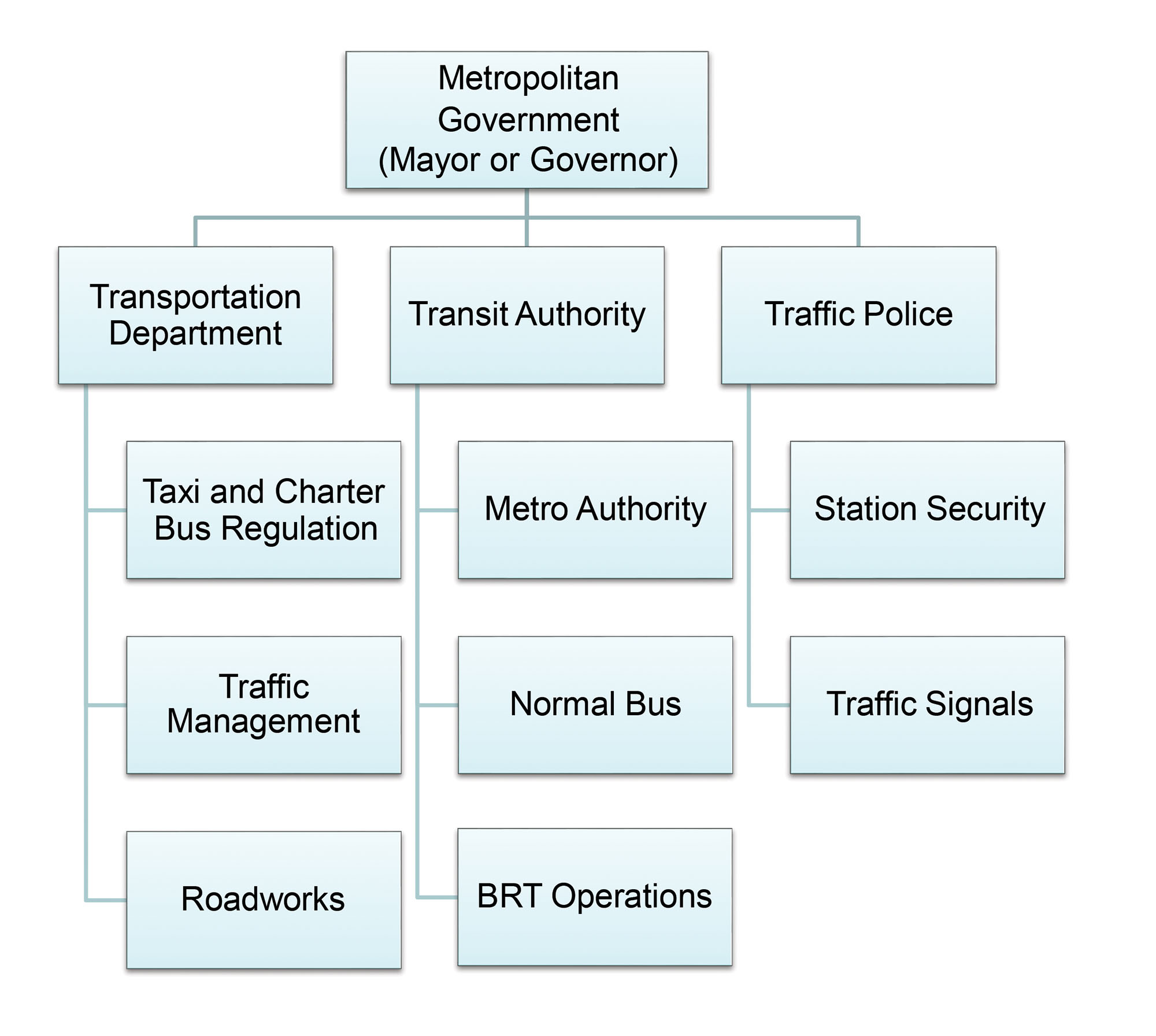

12.4.2.1Transit Authorities

Transit authorities are a form of public benefit corporation that is typically found in the United States and British Commonwealth countries (Canada, Australia). They are generally publicly owned and controlled bodies intended to act like private companies but for the purpose of fulfilling a public service. These entities generally collect and control user fees as part of the mechanism through which their operations are funded.

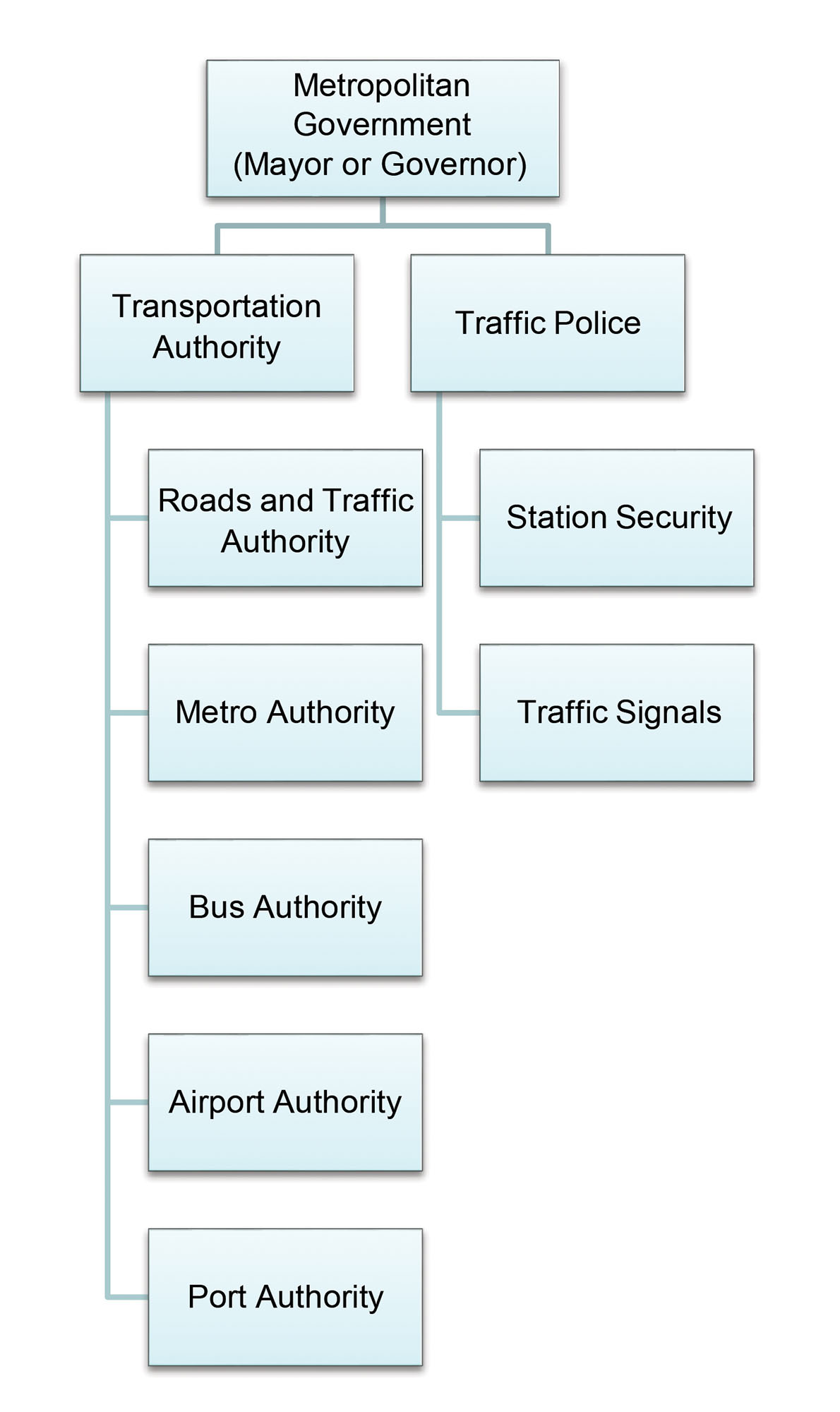

In these countries, it is most common for BRT systems to be managed by a transit authority. A transit authority will generally have a remit over all vehicle operations and rail transit operations in a metropolitan area, but it does not have authority over traffic management.

These transit authorities were not created to run a BRT system but were preexisting institutions already managing bus and rail services when a BRT system began operation. In the United States, these transit authorities are generally the direct operators of public transport services, though about 40 percent of them contract out at least some services to private operators, and a few—mostly suburban bus systems—contract out all of their services to private operators ( Institute, 2015). Hence, there is nothing inherent in the public authority administrative structure that precludes the contracting out of BRT services to private operators.

These transit authorities developed over decades as a result of historical circumstances specific to the suburbanizing cities of the former British colonies as described below. And as such the forms should not be applied to cities in lower-income economies without careful and critical consideration to understand why this administrative form emerged. These conditions are:

- Public transport services that were originally private, but private provision led to a deterioration of service due to disinvestment in the face of declining ridership;

- Public transport services that have ended up serving urbanized areas well beyond the original municipal administrative boundaries;

- Public transport services where the fiscal strength of the municipality is much weaker than that of the surrounding state or county government.

Over time, transit authorities have become relatively successful at operating BRT bus services at a reasonably high quality of service. However, this came only after decades of institution building and massive capital and operating subsidies from state and national governments, sustained over decades. When they were first created, many of them were taking over for failed private operators, and their public transport properties—both rail and bus fleets—were badly deteriorated. As publicly funded enterprises, the quality of their services tends to rise and fall with the strength and weakness of state and local government finances and the degree of political commitment to public transport.

They have been reasonably successful at introducing single integrated fare systems that are usable throughout the public transport network. As the same entity controls the buses and the rail properties, it is relatively easy for this authority to develop or contract out a fare system that is usable in both bus and rail systems.

Typically, these public transit authorities are governed by a board of directors. The board members are often appointed by the chief executives of local governments served by the system and/or by the governor. In Australia, the Brisbane BRT (silver standard) is managed by TransitLink, a public authority controlled largely by the governor of Queensland Province with some board members appointed by local governments in the service area (Transport Operations [TransLink Transit Authority] Act 2008). In the United States, of those cities that have BRT systems that rank bronze or silver (using The BRT Standard as of 2014), all of them were managed by transit authorities. Greater Cleveland’s Rapid Transit Authority (RTA) has a presidency always controlled by the City of Cleveland, but the board includes three representatives appointed by the mayor of Cleveland but approved by the City Council; three representatives appointed by the Cuyahoga County chief executive and approved by the Cuyahoga County Council; and three representatives elected by the heads of surrounding municipalities.

Pittsburgh’s Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway is operated by the Port Authority of Allegheny County. The board of the Port Authority of Allegheny County is appointed by the chief executive of Allegheny County (which encompasses the City of Pittsburgh), leaders of both political parties in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and Senate, and also by the governor. The Los Angeles Metro Board of Directors, which operates the bronze-standard Orange Line, represents the chief executives or their appointees (usually city councillors) from each of the municipalities that are served by LA Metro, supervisors from Los Angeles County, and one nonvoting member appointed by the governor. All of them are typical transit authorities responsible for managing bus and rail operations in the greater metropolitan areas. The Eugene Emerald Express (EmX) BRT is managed by Lane Transit District (LTD), a transit authority controlled by appointees of the governor of Oregon, and it is responsible for all bus services in the Eugene region. It also serves as the regional Metropolitan Planning Authority (MPO) for the region.

All but one of these transit authorities operates their BRT and bus services in-house. The only transit authority that contracts out its BRT operations to private operators is the Las Vegas BRT system. Like the other systems, BRT and standard bus and rail operations in Las Vegas are all ultimately controlled by the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada (RTC). It is controlled by appointees of the various county and municipal governments served by the system. RTC also serves as the regional MPO. However, RTC contracts out its bus services to multiple private operators. The only routes that qualify as BRT under The BRT Standard, the SDX routes (Strip-Downtown Express), are operated by Keolis, which is 70 percent owned by the French National Railway Corporation (SNCF) and 30 percent by a Canadian group of investors. Keolis also operates most of the other bus routes in the southern part of Las Vegas. As such, it is possible for a transit authority to contract out some of its routes.

Internationally, transit authorities are unique for the limited role played by the municipal government, due to the historical reasons described above. State government also controls national level funding in the United States, so whether explicit or implicit, most transit authorities are most heavily influenced by the state governor or provincial governor.

As transit authorities do not control the city streets or national highways, cooperation between municipal departments of transportation and transit authorities has been important to success. If the BRT is on a state highway, then cooperation with state departments of highways or transportation has also been important. Often this relationship is managed informally through ad hoc working groups. Some state transportation departments are more pro-transit than others. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation, which also oversees the Boston-area transit authority, MBTA, is leading BRT efforts and is generally quite progressive. However, there have been conflicts between the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and San Francisco city and county transport officials over the designs of planned BRT systems.

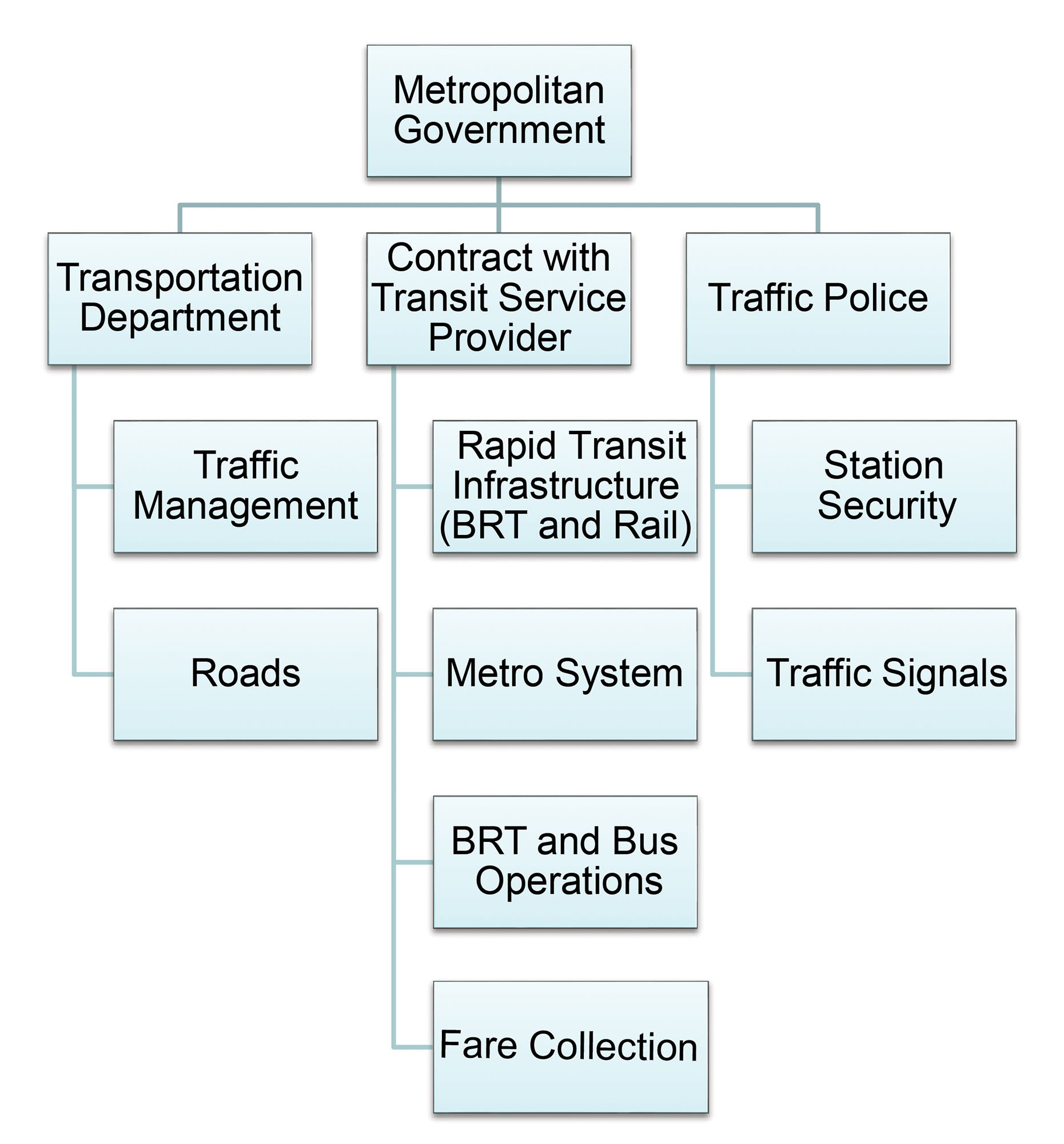

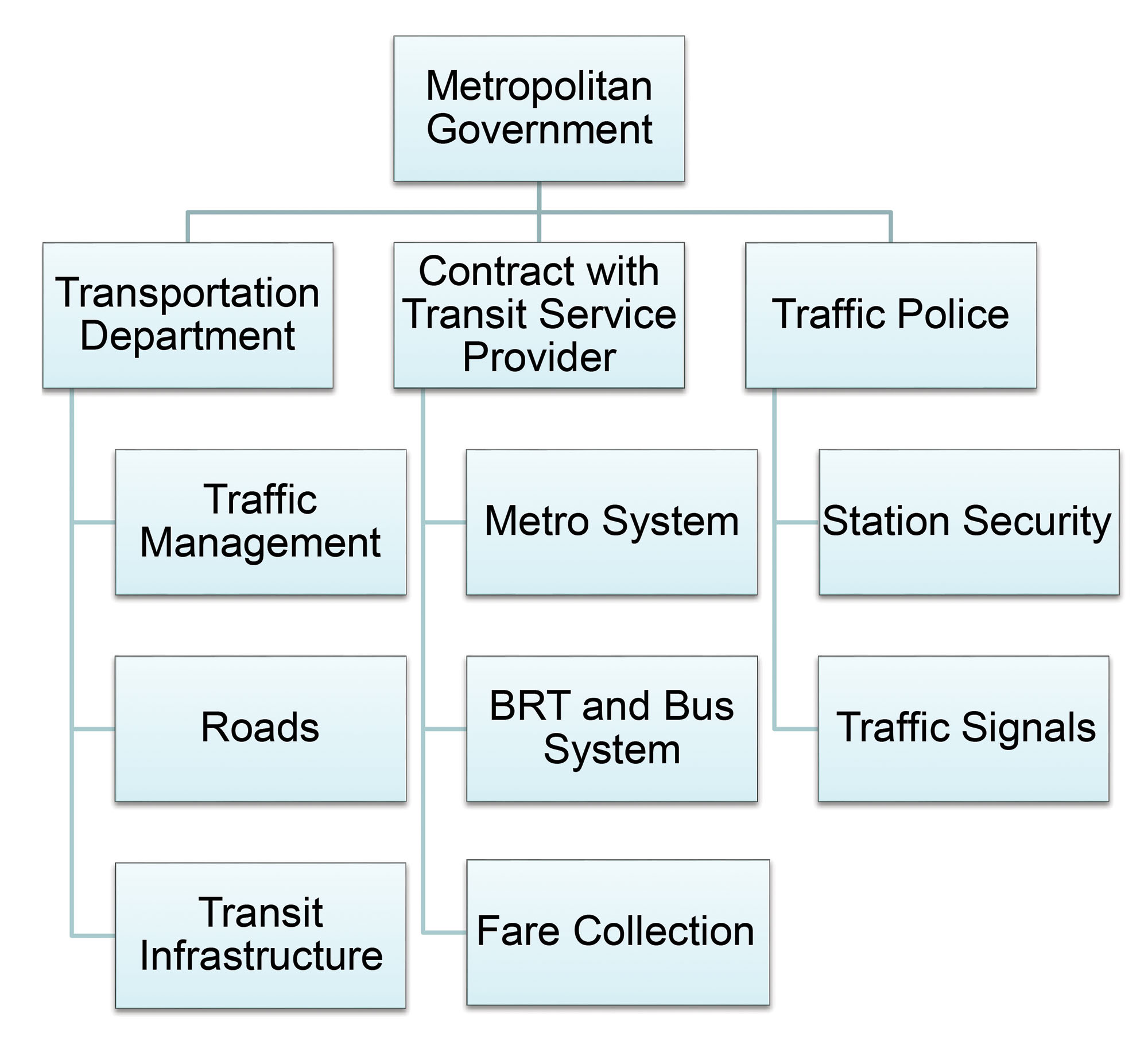

12.4.2.2Integrated Transit Service Providers under Contract to a Municipal, Regional, or State Government

In Europe, and in a few smaller US cities, it is becoming typical for metropolitan areas with BRT systems to contract out the entirety of public transport operations to a private company without the mediation of a transit authority or BRT authority. In these contracts, it is typical that a single firm manages all of the system’s functions, from fare revenue collection to operational controls and planning to bus and rail operations. These firms are sometimes private firms, sometimes firms with both public and private ownership, and sometimes government-owned firms. Policies such as fare levels tend to remain under elected bodies. Public transport infrastructure construction and maintenance is sometimes left to municipal departments, and sometimes it is included in the service contract.

This administrative form achieves many of the system integration and coordination objectives that an integrated transportation agency aims to achieve (see Section 12.4.7 below), but under a slightly different organizational form.

In France, for instance, public transport is generally the responsibility of the regional level of government. This level of government frequently contracts out public transport services to a single large integrated public transport service provider. This company is in some cases a government-owned company, in other cases a joint venture between a regional government and a private company, or purely a private company. In this way, integration of different public transport services becomes the responsibility of a single public transport service contractor. In essence, the transit authority model is re-created inside a transit service corporation, whether it be public, private, or a combination of public and private ownership. In most of the French systems, the services of the BRT system are not contracted out under a separate contract but are just one of many services provided under a single contract.

The Paris Mobilien BRT (bronze standard) is operated by Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens (RATP), the Paris regional public transport service provider that is responsible for all bus and rail services throughout the Paris metropolitan region, and is under contract to the Isle de Paris, the regional government of the Paris Metropolitan Region. RATP functions by all intents and purposes as a private company licensed to perform a public function, but it is a company with the majority of its shares owned by the government. RATP in turn contracts out many of its bus routes, including the Mobilien routes, to TransDev, a private company. Fare collection as well as operations are all under the same subcontract to TransDev. The Rouen BRT is also operated by the same private company (TransDev) that manages all public transport operations, though in this case directly under contract with the regional government (Communauté de l’Agglomération de Rouen Elbeuf Austreberthe) and as part of the contract was also required to construct and operate an LRT system. The Nantes BRT is operated by Semitan, the same public-private consortium that operates the entire public transport system in Nantes. Semitan is a joint venture formed out of the former public vehicle operator, and is more than 60 percent owned by the City of Nantes and about 15 percent owned by TransDev.

The BRT in Amsterdam that serves Schiphol Airport, now called R-Net (previously known as Zuidtangent) is operated under contract to the Amsterdam regional government by Connexxion, a public-private company that is 66 percent owned by TransDev, the same private company involved in many of the French public transport systems. Connexxion does not operate the entirety of the Amsterdam-area public transport system, but it does operate a selection of services, including the BRT.

The Cambridgeshire guided busway (bronze rated) was built by private firms under contract to the Cambridgeshire County Council Department of Economy, Transport and Environment’s Strategy and Development Department. Vehicles along the busway and elsewhere are operated by two private vehicle operators, Stagecoach and Whippet, as part of more general vehicle operating contracts for the Cambridgeshire County Council.

In summary, if a municipal or county government has a well-functioning department of transportation, this municipal or county government may elect to manage multiple contracts to private vehicle operators, fare system operators, and other contractors without necessarily creating a new legal entity to supervise these roles. More research is needed to determine if this administrative structure results in management weaknesses for the BRT operations.

12.4.2.3Transportation Authorities

Most transportation authorities grew out of the consolidation of preexisting transportation agencies and institutions. Transport for London (TfL), created in 2000, is the most famous example of combining these functions. It took over the functions of the previous London Regional Transport Authority, which was created in 1984 out of the Transit Department of the Greater London Council, which had run public transport services in London since 1964 and had also managed the street network. The LRT also controlled the London Underground, a wholly owned subsidiary of LRT called the London Underground Ltd. established in 1985. It also took control of the airport authority, the port authority, and other government companies. Thus, TfL is not a multifaceted integrated agency that was created from nothing. It is largely the planning and board governance functions of a multiplicity of largely independent subsidiary companies with large staffs that have clear responsibilities over the successful management and regulation of a single mode. TfL does not currently operate a BRT system, though it manages some bus lanes such as the Oxford Street bus corridor.

San Francisco’s Municipal Transportation Authority (MTA) is another example of where these functions are combined into one agency. It was also created, in 1999, by consolidating the Department of Parking and Traffic of the City of San Francisco and the Public Transport Commission, which managed the Muni (bus, LRT, cable car, streetcar). There is also no BRT system yet operating in San Francisco. There are plans for BRT on both Van Ness and Geary Avenues, both of which were not initiated by the MTA but by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority, and then transferred over to the MTA for implementation.

Most similar examples of traffic and public transport system management integration under a single administrative unit are in higher-income economies, and all have been amalgamated from functional, preexisting institutions. There is limited experience with such administrative forms in lower-income economies. Transportation authorities were set up in Dakar, Senegal, with Conseil Executif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (CETUD), and Lagos, Nigeria, with Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA), both to manage World Bank–funded projects. The initial proposal for the creation of LAMATA was introduced in 1994. It took until 2002 to pass a law creating LAMATA, and a further revision of the law in 2004 for the institution to function. It was financed out of the World Bank Lagos Urban Transport Project and a product of that project, which was the main promoter of the effort. As of the last report, the Lagos transportation authority (LAMATA) focused mainly on the implementation of the Lagos light-rail system and a bus system improvement, which has some elements of a BRT corridor. Other areas of its mandate, such as traffic management and improvements on some 800 kilometers of roads in the greater metropolitan area of Lagos, and the regulation of the remaining public transport services remain largely unfulfilled, and it plays more of a coordination role in these areas (Banjo and Mobereola, 2012). ETUD in Dakar, Senegal, was also set up to administer loans by the World Bank, with a very broad mandate.

The theoretical advantage of combining these often interrelated functions under a single management structure is better coordination between related projects, possibilities for financial integration of services, cross subsidization of less profitable services, and possible integration of fare technologies. If staff working on one area are unwilling to coordinate with staff working in another area, the issue can theoretically be elevated to a single manager with decision-making authority without having to be further elevated to the political level. The lower the level of government that minor coordination problems need to be elevated to, usually the better the outcome. With a transportation agency structure, issues need only be elevated to the transit agency head. Thus, it is worth considering whether metropolitan areas in the early stages of developing their urban governance institutions should set up authorities such as TfL.

However, these theoretical benefits need to be weighed against the risk of over-encumbering a fledgling institution with more tasks and responsibilities than it can handle. Most large agencies emerged over time, consolidating functions already mastered by their staff, with their administrative authority and competence no longer disputed. In lower-income economies, it is quite common for several departments to claim administrative authority over the same functions, with none of them having the capacity to properly perform this function. Creating a new administrative body in this context, with responsibility over a large number of functions currently controlled by another department of government, without clearly defining these roles and responsibilities in the law, can lead to a compounding of administrative confusion, with several government departments claiming control over key functions.

12.4.2.4Transit Systems Directly Operated by a Municipal or Regional Government Department

There are a few municipal and regional governments in higher-income economies that directly operate public transport systems as government departments. In Japan, the Nagoya guided busway’s infrastructure, meaning the busway’s construction, ongoing maintenance, and management, is managed by a “third sector” public-private partnership called Nagoya Guided Busway, which is under contract to the city government. Buses operating on the guided busway are operated directly by the transportation agency of the City of Nagoya that also operates the city bus system and part of its rail system. In Canada, the Ottawa BRT system is operated by OC Transpo, a department of the City of Ottawa, which was recently created from an amalgamation of smaller municipalities in the Ottawa-Carleton region (hence, “OC Transpo”) (City of Ottawa 2015).