24.7Merging with Mixed Traffic in Narrow Sections

Well, you would have to say what is the criteria to determine the success of any merger? It would have to be that the companies are stronger financially, that they took market share, and they are on a very steady footing in terms of their performance.Kevin Rollins, businessman and philanthropist, 1952-

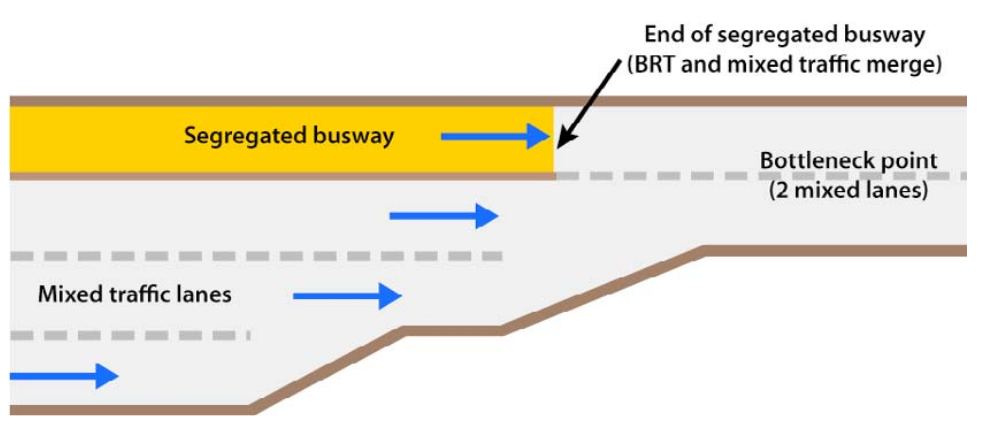

Sometimes a BRT system must pass through a narrow stretch of road that is impossible to widen. Such areas may include bridges, tunnels, city gates, or flyovers. As shown below, having the BRT running with mixed traffic only in this narrow section may not be too harmful for the public transport system if appropriate measures are taken.

This situation can be seen as an intersection (a form of a bottleneck) as there is conflict for using the same space. Usually the heaviest congestion occurs not on the narrow link but just before it, forming a large queue just to enter onto the bottleneck point. When the facility itself is not congested, only the approach to the facility, a traffic signal is generally not needed, and it may be better to end the exclusive busway just a short distance before the bottleneck. The distance should be sufficient only to allow a convenient distance for merging (40 to 80 meters). This curtailment of the busway will allow BRT buses to pass through most of the congestion point without provoking any reduction of mixed traffic capacity at the critical section (Figure 24.64).

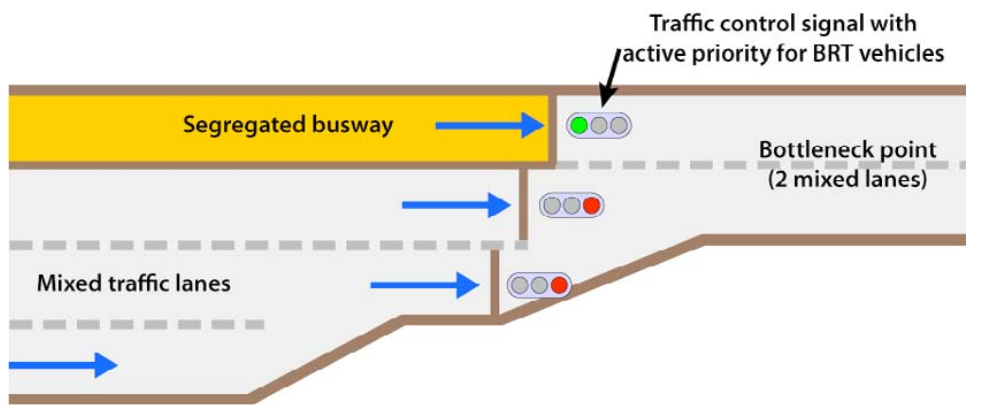

If the critical link is an approach to a signalized intersection (Figure 24.65), then BRT should be given signal priority (active priority if BRT has lower frequency, passive priority in all other cycles), and the head start in the green phase (\( _\text{Theadstart}\)) should be given by:

Eq. 24.26

\[ T_\text{headstart} = {\text{Dist}_\text{stop to narrow section} \over \text{StartSpeed}_\text{BRT}} \]

Where:

- \( T_\text{headstart} \): Time of head start in the green phase;

- \( \text{Dist}_\text{stop to narrow section} \): Distance between the stop line of the signal preceding the narrow section;

- \( \text{StartSpeed}_\text{BRT} \): An average head start speed that the BRT vehicle needs as an advantage over mixed traffic to reach the section first. We suggest 3 m/s (~ 11 km/hour). Using meters and seconds the equation becomes:

\[ T_\text{headstart}[seconds] = {\text{Dist}_\text{stop-to-narrow-section}[meters] \over 3 } \]

The example given in Figure 24.65 essentially acts as a queue-jumping mechanism in which the BRT vehicles are given an advantage through a bottleneck point.

The head start, however, is useless if the facility itself also becomes congested. If there is a risk that the bottleneck facility itself may become congested (due to mixed traffic spillback of conflicts ahead of the narrow section), active signal priority based on the detection of mixed traffic should be used.

The signal before the section would work normally (or if a signal did not exist one would be created and flash yellow) until traffic detectors note that the narrow link has become congested (at its most downstream portion). At that point, the signal would be activated, and a red light would be given to mixed traffic until the narrow section clears. The use of such a traffic signal will help to avoid congestion inside the busway. Instead the delay is transferred to the mixed traffic in the previous link, resulting in improved velocity for BRT vehicles at the narrow link. For tunnels, this approach has the extra advantage of avoiding idling vehicles within heavily polluted conditions.