29.2Pedestrian Infrastructure in Station Precincts

I am a slow walker, but I never walk backwards.Abraham Lincoln, 16th United States President, 1809–1865

For a potential BRT customer, the quality of the pedestrian infrastructure between the home or workplace and the BRT station can make the difference between using the system versus travelling by another mode. A new BRT system offers the opportunity to reevaluate pedestrian conditions and to develop a vastly improved pedestrian environment. The principles introduced in the previous section can help guide the design of the new facilities.

A few meters of quality infrastructure around the public transport station do little to attract customers from their homes and offices. High-quality pedestrian walkways should extend from BRT stations well into surrounding neighborhoods. Most pedestrians approach BRT stations from within a radius of approximately 1 kilometer. Surveys from TransJakarta indicated that 58 percent of customers walked fewer than 500 meters to the station, and an additional 31 percent came from locations within 500 meters to 1 kilometer (see Table 29.1). Therefore, pedestrian facilities should be upgraded at least within a 1-kilometer radius around each station. In order to do this, it may be necessary to evaluate how to integrate BRT implementation plans with the city’s overall urban development plans. (BRT designs normally do not include areas larger than those directly near the station.)

Table 29.1Walking distance at 1.5 meter per second

| Time | Distance |

|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 450 meters |

| 10 minutes | 900 meters |

| 15 minutes | 1.35 kilometers |

| 20 minutes | 1.8 kilometers |

Pedestrian facilities can take different forms, depending on the size of the street, the traffic volume, the character of street usage, and adjacent land uses.

29.2.1Walkways

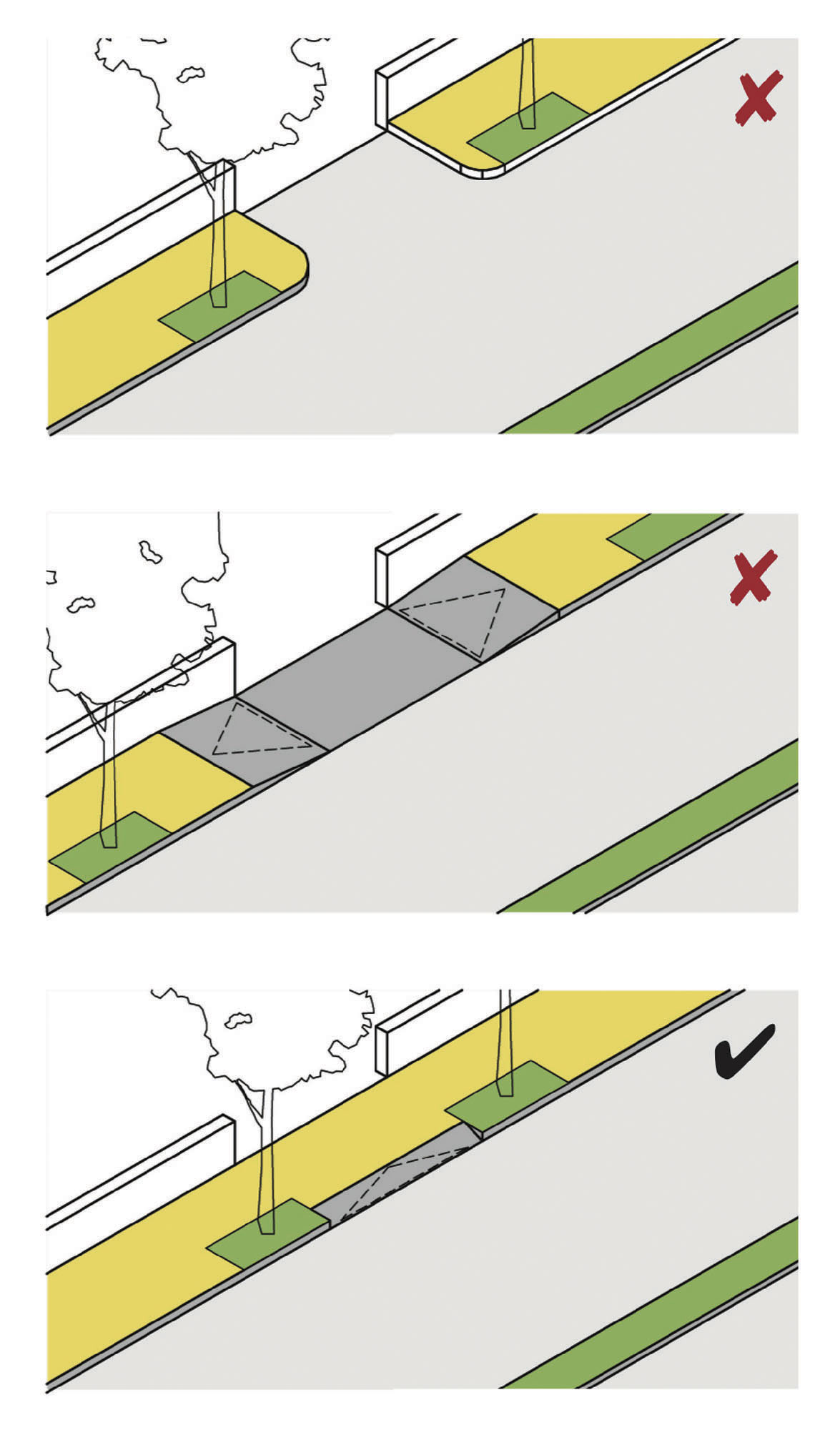

As stated above, reducing pedestrian exposure to fast-moving vehicles is critical to a safe walking environment. On arterial streets where vehicle speeds are likely to exceed 50 kph, it is essential to create a separate slow zone where there is adequate space for walking. If the slow zone takes the form of a sidewalk, it should meet the following design standards:

- A continuous unobstructed effective width of two meters (see box 29.1);

- No breaks or obstructions at property entrances and side streets;

- Continuous shade through tree cover or awnings;

- Separation from the roadway via a vertical curb (100 to 200 millimeters), physical barrier such as a series of bollards, or a setback;

- Adequate cross slope for stormwater runoff;

- Surmountable gratings over tree pits to increase the effective width of the sidewalk.

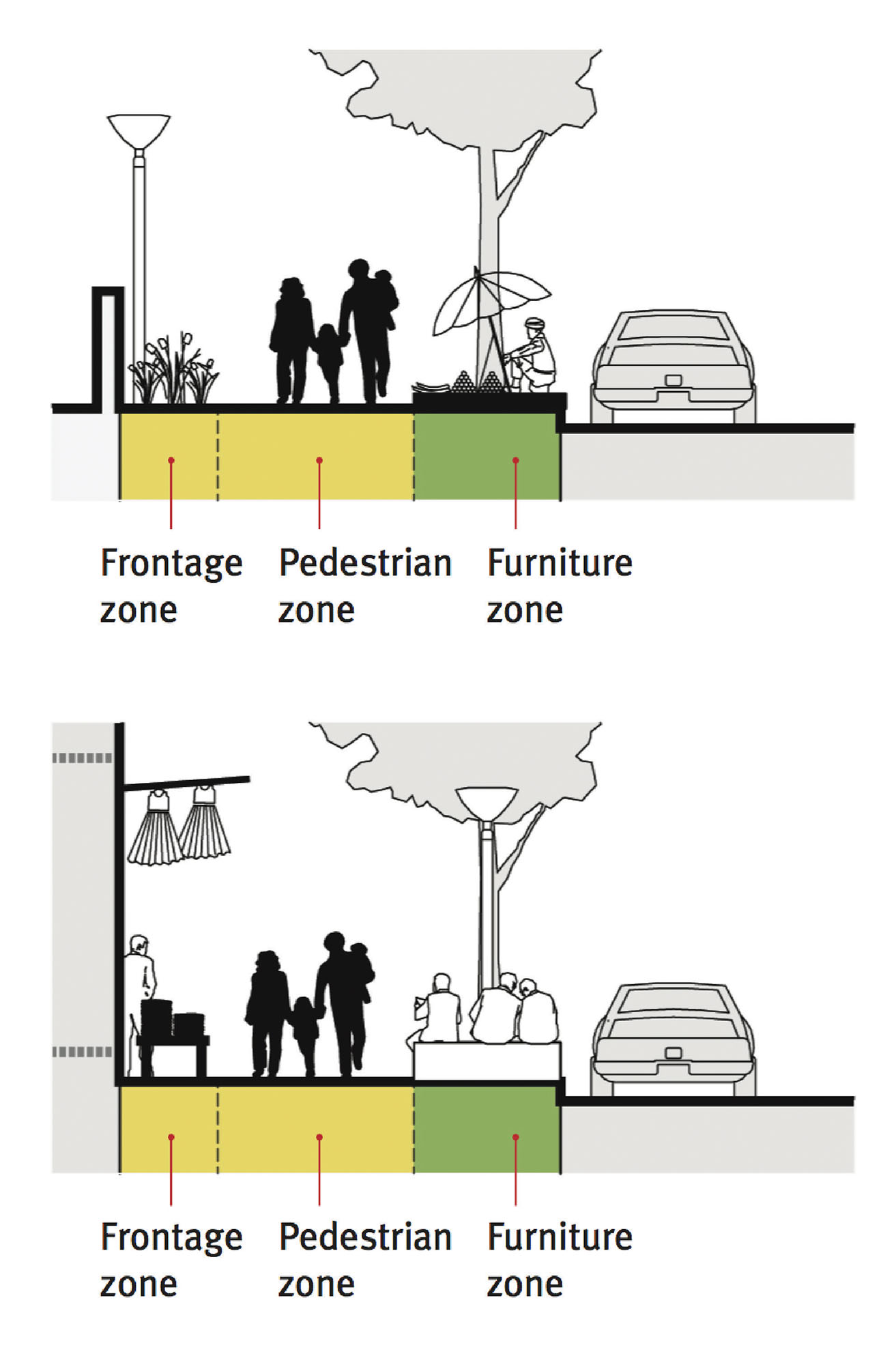

One way of characterizing pedestrian space on sidewalks is the “zone system,” in which sidewalks are divided into three zones that serve separate purposes:

- Pedestrian zone. This zone provides continuous space for walking and should be clear of any obstructions. It should be at least 2 meters wide;

- Frontage zone. Provides a buffer between street-side activities and the pedestrian zone. Next to a compound wall, the frontage zone can become a strip of landscaping;

- Furniture zone. This is a space for landscaping, furniture, lights, bus stops, signs, and curb cuts.

Well-functioning sidewalks incorporate each of these areas to reduce conflicts among uses.

Box 29.1 Defining Effective Width

The notion of “effective width” of a sidewalk is central to sidewalk usability. The effective width refers to the amount of space that is actually available for pedes-trian through movement, and effective width determines the sidewalk’s capacity and the level of pedestrian comfort.

29.2.2Pedestrian Crossings

Formal pedestrian crossings should be provided at regular intervals along all major streets, including the BRT corridor itself. On arterials with great distances between intersections, it is common for pedestrians to cross at random points along the corridor. Providing safe, formal crossings encourages pedestrians to cross in designated locations. This increases predictability and allows pedestrians to benefit from safety in numbers when they cross the street.

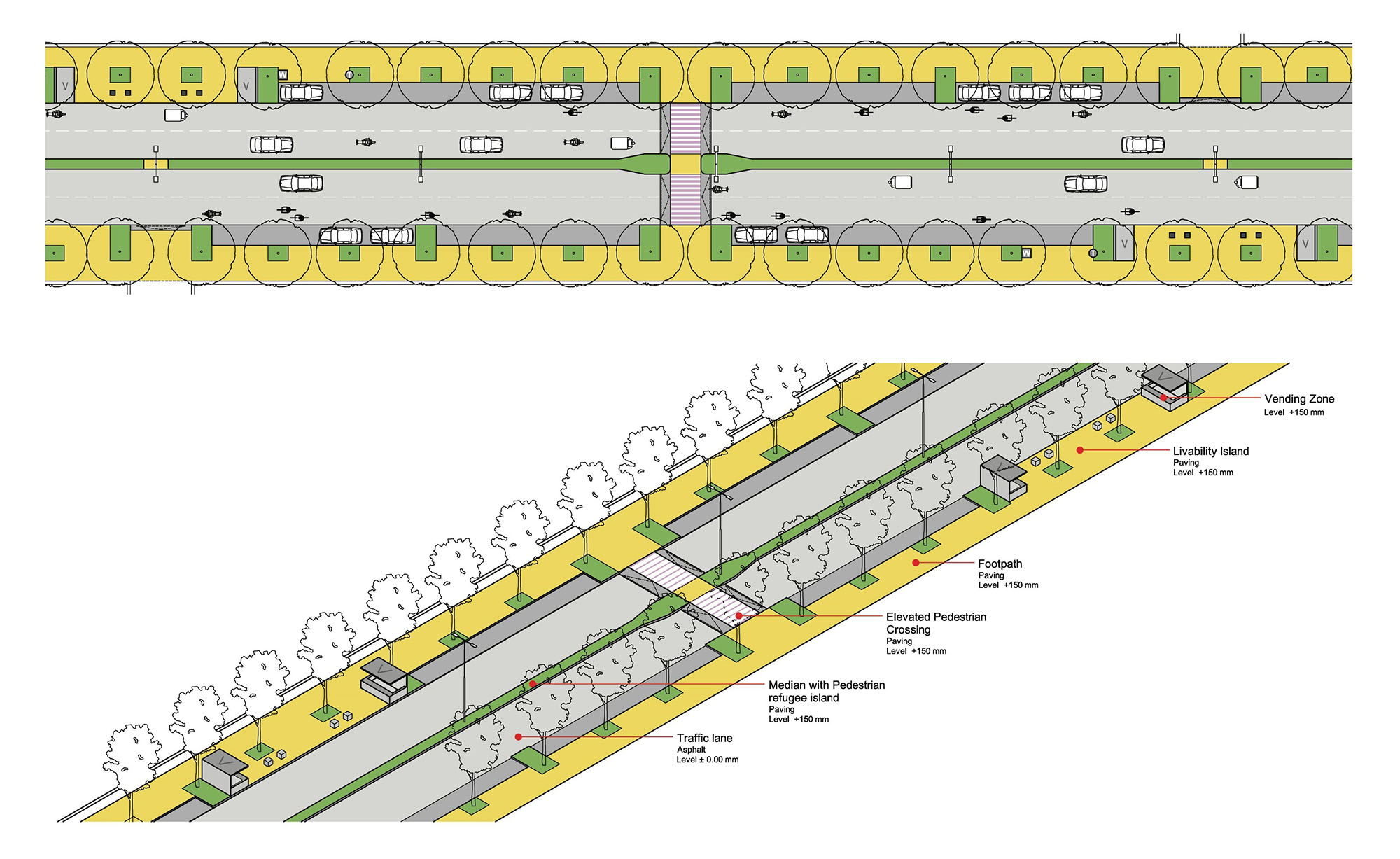

Camera enforcement of speeding vehicles and police campaigns can be effective, but the most reliable method is to employ physical designs that compel motorists to slow down. While slowing vehicle speeds can compromise mixed traffic throughput, recent Dutch research has shown that it can frequently increase mixed-traffic capacity through a process known as “traffic smoothening,” which ends the accordion action that can lead to traffic bottlenecks. Thus, pedestrian crossings should meet the following design standards:

- Except on expressways, pedestrian overpasses and subways are to be avoided;

- Raised crosswalks should be located at all intersections (both signalized and uncontrolled), and at frequent intervals (e.g., every 50 meters). Crosswalks should be as wide as the adjacent sidewalk, and never narrower than 2 meters;

- Raised crosswalks should be elevated to the level of the adjacent sidewalk with ramps for motor vehicles. The ramp should be designed as per the target speed of the street (e.g., a slope of 1:10 yields about a 20 to 25 kph vehicle speed whereas 1:12 yields 40 to 45 kph);

- Guardrails and high curbs are discouraged because they hinder pedestrian and cycle movements. They should be provided only on roadways with a curb-to-curb width of 18 meters or larger. Where fences are present, informal crossings in the form of breaks in the fencing should be provided at regular intervals (e.g., every 50 meters). The opening in the fence should be at least 2 meters in length in order to create a refuge island so that pedestrians do not spill over into the main roadway. Adjacent to BRT lanes, longer stretches of guardrail can be provided, with breaks only at formal crossings;

- At formal and informal crossings, parking lanes should be converted to bulb-outs to reduce the crossing distance and to lower vehicle speeds;

- On an artery where the curb-to-curb roadway width is 12 meters or wider, a continuous median surmountable by pedestrians (maximum elevation 150 millimeters) is advised. In order for the median to function as a safe pedestrian refuge, a minimum width of 2 meters should be provided;

- If pedestrian crossings are signalized, the waiting time should be minimized. The likelihood of compliance with pedestrian signalization falls greatly if wait times exceed 30 seconds (in a similar fashion, elevators are generally designed so that people do not have to wait more than 30 seconds);

- In an additional effort to enhance pedestrian safety, designers should consider including a median strip that will double as a pedestrian island, facilitating safer crossings for all pedestrians. As a result, the median will minimize the number of lanes that a pedestrian has to cross.

29.2.3Intersections

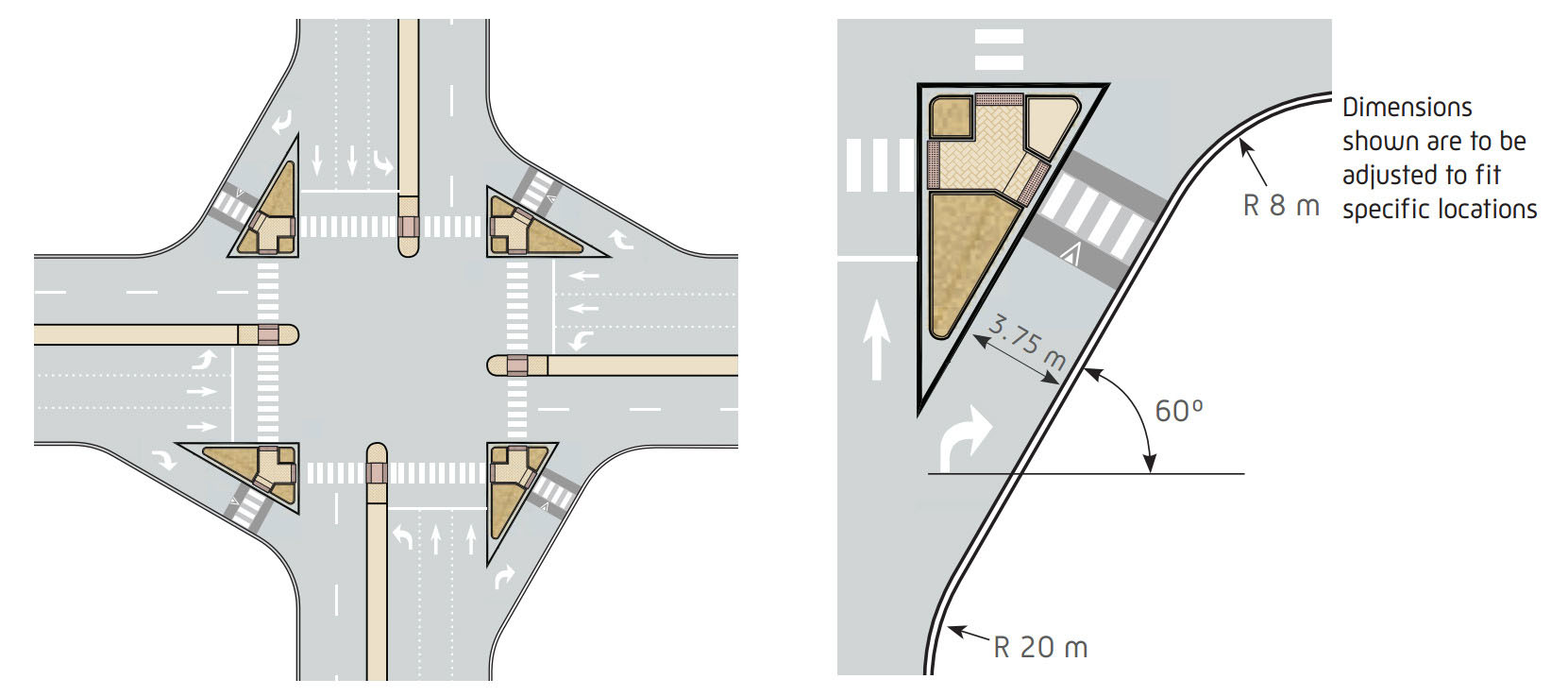

Pedestrian-vehicle conflicts at intersections can be mitigated by reducing turning radii, simplifying the turning movements to two or three phases, restricting free right or left turns where possible, avoiding slip lanes where possible, and using the physical measures described above.

Separating the use of the intersection in time through turning restrictions and signal phasing can reduce pedestrian exposure. Free right and left turns improve vehicular travel times, but they are very dangerous for pedestrians. To optimize the intersection, the vehicular turning volumes should be weighed against the pedestrian volumes and the frequency of crashes. If turning volumes are relatively low, and pedestrian volumes and crashes are high, free right and left turns should be restricted. Reducing the number of phases can also help simplify turning movements and reduce the number of potential conflicts during the green phase of the signal cycle.

Where slip lanes must be maintained, building a pedestrian island and tightening the turning radius can slow turning vehicles, while reducing the distance pedestrians must cross to reach the other side of the road safely. In such cases, a “pork chop” slip-lane design will force vehicles to slow down where they enter the oncoming traffic, just at the point where pedestrians need to cross. A “pork chop” is a triangular island with a “tail” that faces oncoming traffic and controls speed and movements. Pork chops may serve as pedestrian refuges. Coupled with an elevated crosswalk, this slip lane can significantly improve an intersection’s pedestrian safety.

Where separate pedestrian signals are available, a novel technique to reduce pedestrian exposure at intersections is the “leading pedestrian interval.” Under such an arrangement, a pedestrian-only phase begins a few seconds before the vehicle phase. This permits a pedestrian to get halfway across the street and establish their presence in the crosswalk before vehicles start turning, thus increasing the chance that drivers will yield as required.

29.2.4Shared Space

Small local streets where vehicle speeds are low may not require separate pedestrian footpaths. Where a BRT system goes through a city center or on smaller access roads, there may be opportunities to implement “shared space,” in which all physical differentiation between vehicle and pedestrian space is removed.

In shared space, the roadway is designed to look like a public plaza where motor vehicles do not belong, sending a visual signal to motorists that they should slow down. Often, simply redesigning a street to look like a pedestrian zone alone, with no restrictions on motorist access, will fundamentally change driver behavior in this environment. There are no traffic signals or explicit signage to dictate who has priority. People must resort to eye contact and other forms of subtle communication to navigate the roadway safely.

Shared space along a BRT corridor is closely related to the transit mall concept introduced in Chapter 23: Roadway Configuration. BRT vehicles intermingle with pedestrians and other non-motorized users. The sharing of space will likely affect public transport vehicle speeds. However, this concept is successfully utilized along corridors such as Avenida Jimenez in Bogotá, and Line 4 in Mexico City.

Shared space is also relevant to BRT in the context of safe routes to accessing stations. Pedestrian corridors connecting to the station can benefit from an application of shared space, which will reduce speeds of private motorized vehicles and thus encourage more persons to utilize the public transport system. Pedestrianizing pathways leading to the public transport system can be part of a mutually beneficial strategy for both public transport and public space. A pedestrian zone, especially in city center locations, can help concentrate large numbers of customers around the BRT system. The public transport system likewise supports pedestrian areas by reducing the demand for city-center parking. Without high-quality public transport, it is much more difficult to allocate the space needed for full pedestrianization while providing easy access for personal vehicles.