29.3Station Access

Pedestrians are hardly pedestrian, because we all have to cross the road.Robert D. Dangoor, author

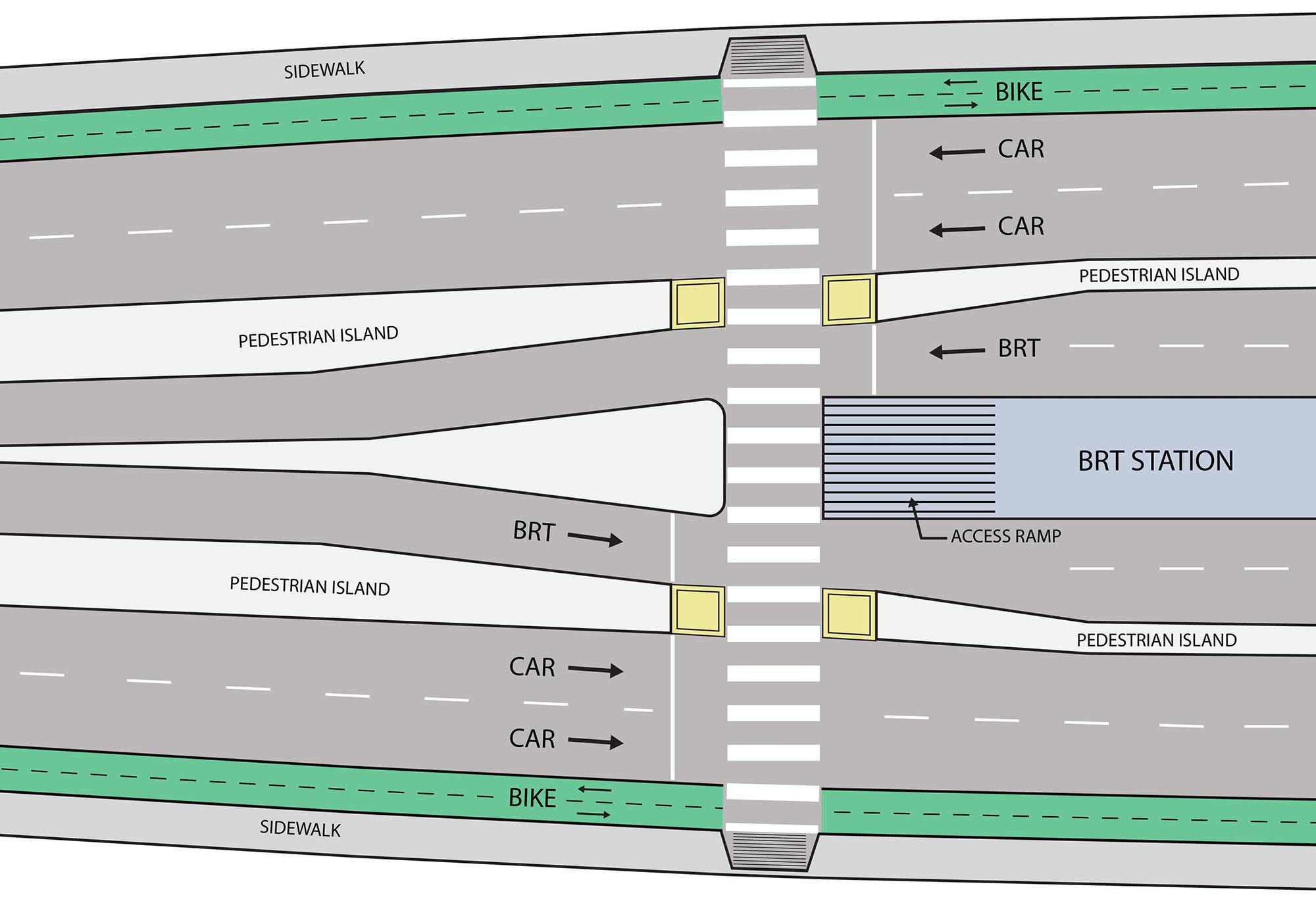

One of the most common questions in the design of a new, center-running BRT system is: “How will the customers get to the BRT station if it is in the center of the roadway?” Safe pedestrian access is required for both standard and BRT systems. Even with normal curbside bus stops, customers need to cross streets for their return trip.

The most significant BRT-access decision is typically whether to utilize at-grade crossings (street-level crosswalks) or grade-separated infrastructure (overpasses or tunnels). As a general rule, at-grade pedestrian crossings are the most convenient way for pedestrians—and people with disabilities—to access a BRT station. As described in the previous section, at-grade crossings can generally be made safe through various traffic-calming measures.

Grade separation reduces the exposure risk to pedestrians, but significantly increases their inconvenience. Pedestrian overpasses or underpasses are usually designed with the primary aim of getting pedestrians out of the way of vehicle traffic—not to enhance the safety and convenience of pedestrians. In cities around the world, pedestrians avoid such infrastructure because it is poorly located, overly steep, badly maintained, or inherently crime-ridden. The narrow confines and infrequent usage of these spaces mean that criminals have greater opportunities for theft and assault. If the overpass or underpass requires walking up and down stairs, many individuals will simply not be able to make use of the infrastructure. The physically disabled, elderly, and parents with strollers will essentially lose access to the public transport system. Studies indicate that 70 percent of pedestrians would use an overpass if the travel time equaled the at-grade crossing travel time, and very few would use an overpass if the travel time were 50 percent longer than at-grade crossing (ITE 1998). Therefore, BRT station access should generally be provided at grade.

There are some conditions where topography, vehicle speeds, and traffic levels may make grade separation a reasonable option. If a median station is flanked by high-volume, high-speed, multiple-lane expressways far from any intersections, the constant flow of high-speed vehicles will be almost impossible to cross. The conditions that may imply the need for grade-separated access to a median BRT station include:

- Four lanes or more of traffic to cross per direction along a high-volume, high-speed arterial or expressway;

- Connecting an underground subway station to a median BRT station (a tunnel will be most effective in this situation);

- Overpass or underpass leads directly to a high-demand destination, such as a sports facility, school, or shopping complex.

Even in these situations, there are design solutions that can frequently make at-grade crossing reasonably safe and feasible. However, if pedestrian overpasses in these conditions are a reasonable option, they may even be preferred if they reduce overall crossing time and improve the walking environment.

29.3.1Designing Effective At-Grade BRT Access

When the BRT station is at or near an intersection, pedestrians can cross with the rest of the traffic during the green signal phase. Measures suggested above for safe intersection design are generally applicable: elevating crosswalks across slip lanes; creating additional pedestrian-refuge space; reducing vehicle-turning radii; and extending medians. Signal phases should be planned to prevent conflicts between turning vehicles and pedestrians.

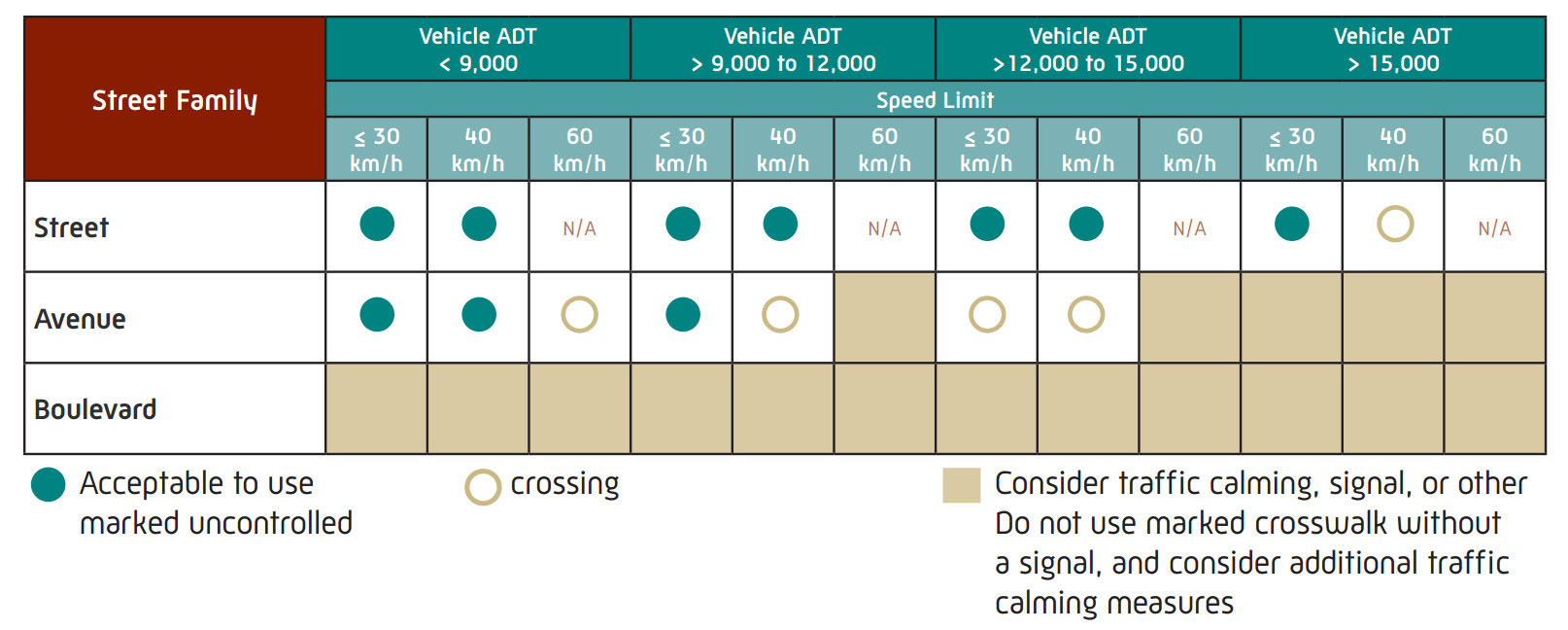

BRT stations are often placed away from intersections to increase queuing space for public transport and private vehicles at intersections. When the BRT station is mid-block, a few additional design considerations apply. The crossing should include elements that signal to the driver that he or she is approaching a pedestrian crossing, such as signs, lighting, vertical markers, and overhead indicators. As described in the previous section, an elevated crosswalk or a speed bump placed before the crosswalk helps force motorists to slow down. Pedestrian-refuge islands between lanes and narrower lane widths also reduce pedestrian-exposure time. Using different surface colors and textures will draw further attention of motorists. Lighting at the crosswalk at night is important.

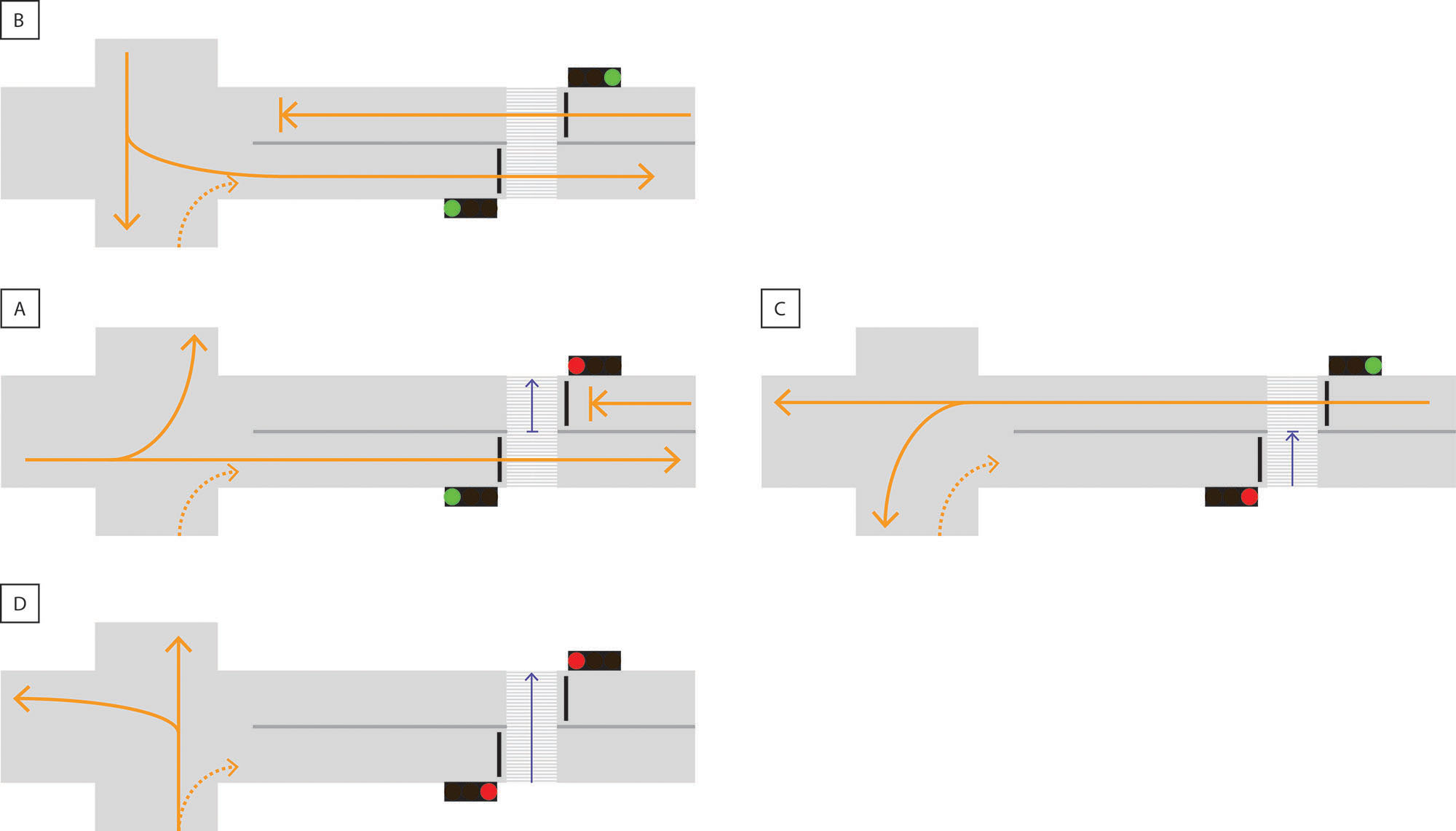

Several different types of signaling options may be employed at mid-block crossings. If pedestrians only have to cross two lanes, and where speeds and vehicle volumes are not that high, signals may not be necessary at all. As traffic speeds, volumes, and lanes increase, the need for standard red-yellow-green signals mid-block also tends to increase.

It is generally possible to signalize the crossing for the mixed-traffic lanes while allowing bus vehicles to continue without a light. Pedestrians then cross the busway whenever a gap appears. At higher vehicle volumes, the public transport vehicles should also be controlled by a traffic signal. Especially in BRT systems with very high demand (i.e., over 10,000 customers per hour per direction), an additional pedestrian-refuge island should be provided between the BRT lanes and the general traffic. This island can be dimensioned to a convenient size for the projected customer demand.

Station areas are prone to unpredictable pedestrian behavior, as customers have a tendency to run to catch an approaching bus or train without paying attention to signals. Motorists may not be expecting this type of pedestrian movement, particularly in mid-block locations. Therefore, at-grade crossings should be placed as close to the station entrance as possible. Otherwise, customers may simply cross at an uncontrolled point closer to their intended destination. Planners should strive to fully account for likely human behavior whenever designing a pedestrian crossing.

The areas to the side of the roadway should allow for clear visibility, so that the sight lines of both pedestrians and vehicle users are unimpeded by signage or vegetation. Signage for the BRT system, trees and shrubs, and other potential obstructions should be carefully placed to avoid blocking pedestrian sight lines.

29.3.2Designing Effective Grade-Separated BRT Access

When designing grade-separated pedestrian access, the following design considerations come into play:

- Illumination. Overpasses and tunnels should be well lit to increase security;

- Visibility. There should be clear lines of sight between the bridge or tunnel, station, and street to increase security;

- Width. Overpasses and tunnels should be wide enough to accommodate peak-hour demand;

- Ramps, escalators, or elevators. The overpass or tunnel should be accessible to a person in a wheelchair, a parent pushing a stroller, someone with a bicycle or packages, or one who has trouble climbing stairs. If elevators are used, stairs must also be provided for circumstances when the lifts are not functioning;

- Flood protection. Tunnels must be supported by an effective drainage system;

- Cleanliness. If the bridge or tunnel is perceived as unsafe or unclean, it will not be used, regardless of the design.

The design of overpasses in Bogotá demonstrates how an effective grade-separated solution can be achieved. Bogotá provides a ramped entry to the overpass, with a gradual slope to ease the climb. Customers typically also have the option of a stairway if they wish to access the overpass more quickly. Utilizing a 2.5-meter-wide pedestrian space and an open design, Bogotá’s pedestrian bridges alleviate many of the security concerns normally associated with overpasses. The long ramp may be an inconvenience for some; it is possible to have shorter, steeper stairs for the able-bodied, such as in Beijing.