1.2Political Commitment

I have never learned to tune a lute or play upon a harp, but I can take a small and obscure city and raise it to greatness.Themistocles, Athenian statesman, 525 BC–460 BC

Ultimately, though, a project concept must enter the political mainstream in order to move toward official development. A leading political official must make a strong commitment to overhauling the city’s public transport system. Political will and commitment are probably the most critical and fundamental components in making a new system a reality. Outside groups can certainly help create the right conditions for project consideration, but as a public good, public transport requires political support to become a reality.

While almost all political officials will claim to hold strong political will and commitment to public transport, the reality is often quite different. Is an official willing to give priority road space to public transport over private vehicles? Will the official risk upsetting powerful lobbying groups, such as existing transit operators and private motorists? Will the officials seek out the best technical help they can find, and the best financial resources to make a project happen? Convincing officials to say yes to each of these questions is the basis of establishing project commitment. “Political will” are just words until backed up by tangible evidence of a serious intent to fully implement a project.

There are some risks associated with having one particular individual or party largely responsible for developing a bus rapid transit project. In Bogotá and Guadalajara, Mexico, for example, the fact that one politician or political party promoted and implemented the BRT system has made it more difficult to expand after that individual left office. Thus, political will is important to the success of the project, but the initiative itself should be neutral—associated more with the city itself and not an individual.

1.2.1Political Officials

The creation of a political environment suitable to introducing a new public transport system can depend on many factors. There is no set amount of time required or set series of events. In the case of cities such as Bogotá and Curitiba, the election of dynamic mayors who entered office with a new vision was the determining factor. Both former Mayor Enrique Peñalosa of Bogotá and former Mayor Jaime Lerner of Curitiba came to office with a strong intent to improve public space and transport (Figures 1.4 and 1.5). They also possessed a base knowledge of these topics and brought with them highly trained professionals as their core staff. In such instances, the progress toward system planning happens almost immediately.

In other instances, a long period of persuasion and information gathering will precede the commitment. Naturally, the more senior the political figure leading the cause, the more likely the official’s influence can lead to action. Thus, mayors and governors are the logical targets for gaining political support. In many cases, as in Jakarta, Indonesia, key local politicians often quickly realize that BRT can help them politically because it can show results within the length of their administration. In some developing cities, support from national ministry officials may also be necessary for project approval. The role of national officials may be particularly important in capital cities.

In many instances, a mayor or governor will lack the necessary background on transport or urban planning issues. It requires confidence to grapple with a widespread transformation of the public transport system. In such cases, building the trust of the decision makers and giving them the necessary confidence to implement such a seemingly far-reaching proposal will be key. Political officials will be averse to risk with key constituencies, such as car owners and transit operators, unless the issue is a core part of their platform.

Further, mayors and governors are busy individuals juggling an array of issues and interests. The amount of time these officials can devote to a studied consideration of a public transport transformation is limited. For this reason, it may be more effective to target the top advisers of a mayor or governor. Such individuals may be able to give the idea greater attention, and then subsequently be in a position to make a trusted recommendation to the official.

However, even in the absence of support at the highest levels, a strategy to begin influencing officials at lower levels may still merit effort. Fortunately, there are many other starting points within the city’s political and institutional environment. Deputy mayors, deputy governors, and councillors are also relevant positions from which a project can be launched. Among such officials, it may be more likely to find a specialist with a background in transportation, environmental issues, urban planning, or other related fields. In such cases, the learning curve will likely be less. In Johannesburg, South Africa, the effort was led by a councillor who was the adviser to the mayor on transportation.

Another useful starting point can be unelected officials holding key positions within municipal institutions. Directors and staff within departments of planning, public works, environment, health, and transportation will all likely play a role in any eventual project. Without the support of such officials and staff, institutional inertia can delay and weaken implementation. Further, these officials often have a direct relationship with top elected officials. During their daily or weekly briefings, technical staff can prompt a discussion of public transport options. A concept being supported by both citizens’ groups and departmental directors will stand a better chance of approval by a mayor than a project being pursued by just one outside group.

The best strategy is to approach all relevant officials, both elected and appointed, who may be influential on public transport. Even if an official is unlikely to become an overt supporter of a public transport initiative, eliminating the threat of overt opposition is equally important. Thus, an initial preemptive session with the potential opposition can be vital to reducing any strongly negative reactions. Much care must be given to the manner in which the issue is presented to any given audience. In fact, the key points to be stressed will likely vary from one official to another, given their different starting points and initial understanding of mass transit options.

One common and rather unfortunate complication is the existence of opposing political parties in key positions overseeing the project. For example, if the local government control is held by one political party while the regional or national government is held by another party, then cooperation to make the project a reality may be lacking. The lack of cooperation between national and local officials scuttled the Bangkok BRT project until it was finally launched in May 2010 after various delays. While local government will typically have direct implementation responsibility, approval from the national government could be required for either budgetary or legal reasons. In Colombia, the success of TransMilenio in Bogotá generated a strong commitment to implement eight more BRT systems throughout the country, with a contribution of up to 70 percent from the national government. Something similar happened in India, where the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) was developed as a financing mechanism to implement suitable public transport solutions for its cities, some of which have been designated as BRT systems.

The duration of the political administration’s time in office (and the possibility for reelection) is also another key factor to consider. If a mayor or governor has only a short time remaining prior to an election, then such officials may be reluctant to embark upon bold initiatives. The risk of alienating potential voting groups can override any political boost that a project announcement could garner. Further, once an incumbent takes a strongly favorable position on a public transport option, this position may imply an equal and opposite reaction from the opposition candidates.

For these reasons, catching political officials at the earliest stages of their time in office provides the best chance for achieving commitment to implementation. Often, a major selling point for mayors and governors of an option such as BRT is that it can be built easily within a single term of office, helping establish the politician’s career. It may also be effective to introduce public transport options even prior to officials taking office. Providing information to staff within the major political parties can be a worthwhile investment of time and effort. Identifying potential future leaders and establishing a mentoring relationship with them can be equally useful.

1.2.2Awareness-Raising Mechanisms

There are several different mechanisms available to help alert political officials to the potential of various public transport improvement options. These mechanisms include:

- Site visits to successful public transport systems;

- Tours of own city’s existing public transport services;

- Visits from successful mayors and other successful implementers, such as the directors and commissioners of transport departments;

- Basic information provision on options;

- Videos on public transport improvement examples;

- Simulation videos of potential systems in the particular city;

- Physical models of public transport options;

- Pre-feasibility study.

These various mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, as several different information techniques can be combined to build a case on the need for change. Frequently, all it takes to generate political interest is to provide fairly basic information to mayors and other decision makers.

In most cases, however, firm political resolve only comes after chief decision makers visit a successful system like Mexico City or Guangzhou, China, to see it and understand it for themselves. “Seeing is believing” is completely true in the case of BRT. Usually, the decision makers are also accompanied by senior technical staff who will be responsible for implementing the project. Members of the city’s media, as well as existing transport operators, may also participate in the visit. By speaking directly with technical staff and political officials in cities with existing systems, prospective system developers can understand the possibilities in their own cities (Figure 1.6). Experiencing a high-quality system in a relatively low-income city, such as Quito, Ecuador, also shows city officials that a system is possible regardless of local economic conditions. In many instances, the process of developing a new public transport system can seem quite overwhelming at the outset. Seeing systems in practice and walking through the development process can do much to dispel uncertainties and fears. At the same time, care should be exercised to avoid giving the impression that project implementation is always easy, fast, and problem free.

Surprisingly, political officials and even municipal technical staff can be relatively unfamiliar with public transport in their own city. Given the background and income levels of such persons, many will utilize their own private vehicles for transport. In the case of top elected officials, their only view of daily transport issues may be from the back of a chauffeur-driven luxury vehicle (Figure 1.7). Thus, public transport systems are frequently conceptualized and designed by individuals with little actual familiarity with the daily realities of public transport.

Organizing a tour of the public transport conditions in an official’s own city can be an eye-opening experience for the official. In cities such as Bogotá, Delhi, Johannesburg, and São Paulo, officials have either made a point to regularly utilize public transport and/or have required staff to use public transport for certain periods of time (Figures 1.8 and 1.9).

Testimonials from one political official to another may sometimes be appropriate. Visits to cities by prominent former mayors such as Enrique Peñalosa and Jaime Lerner have been sponsored by international organizations to help catalyze local actions. Showing how mayors and governors who delivered high-quality systems have tended to win subsequent elections can also be quite motivating to local officials.

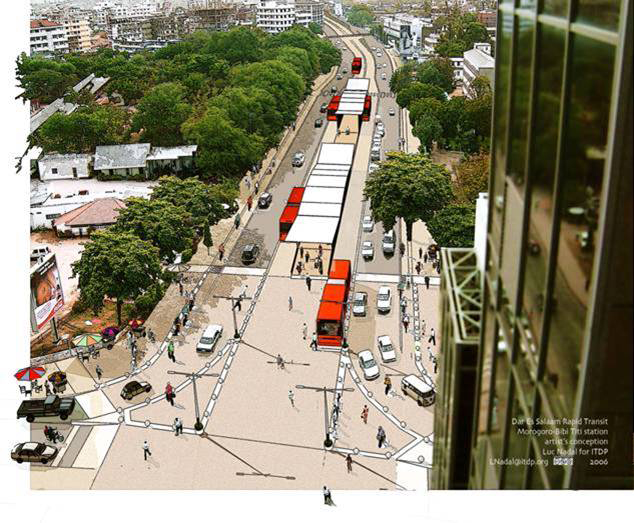

Advances in information and communications technologies (ICT) have put the power of sophisticated visual and software tools in the hands of most municipalities. Visual renderings of stations, vehicles, and runways can do much to excite political officials over the possibilities (Figure 1.10). Videos of high-quality public transport systems in cities such as Bogotá, Colombia; Brisbane, Australia; and Curitiba, Brazil provide an accurate visual display of the options to decision makers. Likewise, digital video technology is now available to simulate how a new system would actually operate in a city of interest. Being able to “virtually ride” the new system at an early stage in the planning process cannot only work to stimulate political commitment but it can also help planning staff with design considerations. In a similar manner, small models of vehicles, stations, and runways all help give political officials a hands-on feel with the possibilities (Figure 1.11).

A pre-feasibility study is also an effective mechanism to build initial interest in public transport improvement. The pre-feasibility work can include the identification of major corridors for public transport development, early estimates of potential benefits (economic, environmental, social, etc.), and approximations of expected costs. This work will be fairly superficial, but will at least give decision makers a degree of confidence in a possible project direction. The faster and more compelling this early vision of the new system, the easier it will be for decision makers to build the necessary political commitment to move forward. This early vision will be needed to persuade the public and interested parties to support the project, and to guide the information-gathering process.

The techniques for achieving project commitment are varied, and can depend greatly on the local context, but the principal aim is to get the chief decision maker to make a public commitment to implementing a major transformation of the public transport system, and to create a sense of expectation among members of the public.