3.4Planning Team Structure

The strength of the team is each individual member. The strength of each member is the team.Phil Jackson, basketball coach, 1945

The planning and establishment of a new public transport system within an existing urban environment is a huge challenge. Although the initial concept may have germinated in the context of existing planning duties, it is advisable to structure, motivate, and select a dedicated BRT team to develop the planning phase of the system. A quality BRT system can only be achieved within the desired time frame through the appointment of a dedicated, full-time team of professionals in a carefully considered employment structure.

3.4.1Team Entity

There are two different philosophies regarding the selection of a development entity for the new public transport initiative. Some cities assign the project to one of the existing agencies, departments, or cost centers with responsibilities related to public transport. These responsibilities may currently be limited to infrastructure, public services, or transport regulation and policies. Related responsibilities could also include finance, air quality and pollution control or other environmental responsibilities. The other philosophy is to create an entirely new organizational entity to plan and implement the BRT system. This new entity may draw upon existing agency staff, but in general would represent an entirely new team.

Each of the two options has its advantages. Utilizing an existing agency means that the development team would be familiar with the current public transport situation. The existing relationship between the agency and transport operators could also be advantageous if a history of trust and cooperation is present. Furthermore, by not creating a new entity, existing groups should not experience professional territorial conflicts. Any newly formed BRT organization may have overlapping responsibilities with the existing agencies, resulting in duplication that may cause confusion, administrative conflict, and ineffective use of resources.

An entirely new organization offers the advantage of bringing a new perspective to the local public transport system, whereas existing agencies may be too involved with the current context to take the lead on a new initiative. In some cases, the existing agencies may be held accountable for the existing poor quality or lack of efficient public transport in a city. An entirely new entity will not be as susceptible to the constraints of existing customs, biases, and processes. Additionally, the skills to deliver a successful BRT system can be quite different from the skills required to regulate conventional public services. BRT development tends to be significantly more customer orientated and more entrepreneurial in nature. Some cities find that a dramatic improvement to the public transport system can only be achieved through the efforts of a completely new structure or entity.

Some cities may decide to defer the final choice of agency supervision for a new system until later in the BRT development process, and employ a temporary, ad hoc team for the oversight of the BRT planning phase. The decision on the eventual organizational structure can then be determined through the planning process itself. At the outset, a decision can be made that the planning team will essentially be disbanded once the work is completed and the system is fully operational.

There are examples of each type of approach. São Paulo, Brazil, and Santiago, Chile, developed their new BRT efforts through existing organizations. São Paulo’s Interligado system was coordinated by the secretary of transportation, with the participation of the bus authority (SP-Trans) and the traffic authority (Institute of Traffic Engineering). São Paulo’s organizational design was likely influenced by the fact that Interligado was a priority project of the mayor and a strong institution already existed.

Santiago created a BRT project office within the national Ministry of Transportation. This office coordinated efforts of the other contributing organizations, such as the Secretary of Transport Planning (SECTRA), which was responsible for the technical aspects of the BRT system development. Santiago also formed a project committee consisting of cabinet-level officials and other key leaders, including the Ministry of Housing, Ministry of Finance, and the president of the Santiago Metro. Santiago’s BRT planning team structure reflects the strong nature of central government institutions in overall decision making.

In contrast, Bogotá, Colombia; Lima, Peru; and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, have all created new entities to develop their systems. From the outset, Bogotá created a project office that reported directly to the mayor. This project office also coordinated efforts from other city agencies, and eventually became the formal oversight agency for the implementation and operational management of the TransMilenio system. Other Colombian cities have followed the same model, particularly due to the fact that national legislation in Colombia makes a specialized agency compulsory in order to receive national grants. In a similar manner, Lima has also created a special BRT project office, which has now transformed itself into a city agency called PROTRANSPORTE.

Due consideration should be given to the fact that the most ambitious BRT plans have emanated from newly created project offices or agencies. Bogotá and other Colombian cities stand out as high-quality BRT systems. By contrast, the São Paulo and Santiago systems are possibly further from being considered full BRT, especially when compared to systems that have been developed from a new institutional perspective. Thus, newly created entities may have an advantage in terms of being able to go well beyond established thinking and develop a superior quality public transport system.

In South Africa, a variation of the above has been employed, where new departments have been created within existing municipal structures, complemented by strong professional teams. The level of rollout of the individual systems in the major cities in South Africa will still have to be evaluated over time to understand the level of success in this methodology.

3.4.2Team Members

Through the process of initial motivation and approval for the BRT system and the start-up phases of the project, the number of dedicated team members could vary, but should generally be relatively small. The initial team should likely have a flat structure, where each individual carries sole responsibility for a function. Unless a concerted restructuring process occurs, this initial team would then form the basic structure for the future BRT team.

Although it may be feasible and more advantageous for the relevant authority to outsource some of the functions or actions to consultants, the technical competence and commitment of the in-house team are crucial to ensuring the appropriate levels of and time frame for decision making.

It is widely assumed that the core team members should focus predominantly on large budget items during the start-up and planning phases, such as infrastructure and vehicle specification. This assumption is supported by the fact that these items generally have the longest implementation or manufacturing lead times. However, ignoring the operational and system planning at this stage will result in the infrastructure team’s working in isolation from the future operational requirements, or being forced to also assume the role of operational and system planners.

The natural tendency to populate the team with engineers, as engineers usually lead transport projects, has merit in terms of their ability to formulate and motivate the original concepts. True value is added by bringing on board team members that are proficient in liaising with public officials, politicians, corporations, various players in the transport industry, media, and affected groups.

The ability of the team to communicate, be innovative, and formulate strategic interventions will be central to the success of the project. As with all new interventions that would change and challenge the status quo in the urban environment, the success of the team may lie with individuals who relish the challenge, are passionate about public transport, and are not risk averse!

Special care should be taken when selecting the project coordinator or executive. This individual should have well-developed management and communications skills, extensive experience in the creation and consolidation of new concepts, and must have a close and positive working relationship with the project champion. Although it would be advisable and advantageous for the project executive to have a keen understanding of the concepts and execution of public transport systems, it is essential that the project executive is focused on the management and coordination of the project and the project team. Depending on the project executive to fulfill key technical functions of the project will detract from the impetus of the project in a wider context.

As BRT is growing from a relatively new concept to an accepted contribution to public transport on six continents, more information sharing and technical training opportunities are available. This is widening the general knowledge base and the number of appropriately trained professionals, thereby allowing the further population of the BRT project teams.

Once the BRT concept is adopted and the initial planning phase has commenced, the project champion and project executive should target a more appropriately staffed team to better deal with the fast number of work streams and targets to be achieved for the successful planning and implementation of the BRT system.

Careful attention should be paid to the continued training of in-house project teams, to keep up with the knowledge and implementation experience gained by private consultants who are more likely to work on different BRT projects in their careers. Opportunities for knowledge transfer between consultants and officials should be facilitated.

3.4.3Consultants

Appropriate Role of Consultants

The appointment of consultants on a BRT project could be a cost-effective way of gaining key technical experience, if managed appropriately. The skills offered by consultants who have already been involved in, or, more important, responsible for the implementation of successful BRT projects elsewhere, will benefit the project and in-house team without the cost implications associated with full-time employees within the organization or local authority.

Perhaps more important, consultants assist in avoiding the pitfall of needlessly reinventing lessons already learned elsewhere. International consultants with significant BRT experience can help smooth the path from planning to implementation. It is highly likely that such consultants have experienced or witnessed firsthand many of the problems facing the local team, and can therefore propose and plan for effective solutions. A local team working in conjunction with experienced international professionals can ideally result in a combination of world best practices and local context.

In looking closely at recent BRT projects, the positive influence of consulting expertise from previous successful projects is noticeable. With Curitiba’s early success in BRT, Brazilian consultants were particularly involved with the subsequent initiatives in Quito and Bogotá. To this day, Brazilian consultants are closely tied to several other initiatives, including BRT projects in Cali, Pereira, and Cartagena, Colombia; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and Johannesburg, South Africa. Subsequently, Bogotá’s highly acclaimed success has boosted the careers of those associated with TransMilenio. These consultants have been involved in a wide range of initiatives, including projects in Cape Town, South Africa; Lagos, Nigeria; Guatemala City, Guatemala; Lima, Peru; Mexico City; and Santiago. Consultancies from more developed nations have also made their impact, with consultants from the United States and Spain making substantive contributions to projects such as those in Bogotá and Lima. Thus, a BRT project may not only enrich a city with a new and efficient public transport system, it may also spawn a new local service industry catering to the exportation of BRT expertise. This is currently evident in South Africa, where several other cities are now benefiting from the BRT lessons learned in the inaugural projects in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

A city should not become overdependent on international consultants. The local context is still best realized by local staff with a fully staffed agency, or with the support of local consultants. The responsibility for key decision making must ultimately still rest with local officials. Although this is usually the protocol embedded in the existing statutory processes, it also adds to the depth and value attached to these key decisions by the public and other stakeholders.

Consultants are one of several valuable resources that lead to knowledge sharing. A prudent strategy could involve building the capacity of the local staff while simultaneously making selective use of consulting professionals. Local consultants can gain international best-practice knowledge and experience working with international experts, absorbing this knowledge to apply in the local context, and contributing to the capacity of local staff. This not only shares existing knowledge of BRT, but adds to the international knowledge base, as local context leads to alternative solutions and applications of the core principles of BRT.

Consultant Selection and Appointment

While some cities have developed well-designed systems without significant assistance from outside consultants, many cities find it advantageous to at least partially make use of people with previous BRT experience. However, procuring consultant services can be difficult for authorities with limited reference to the BRT experience available in the form of international consultants. There is often a bewildering number of people who claim to have BRT experience. Given the vast variety of BRT definitions and experiences, the perspectives and abilities of the consultants can differ greatly. Thus, establishing a rational process for evaluating potential consultants can help ensure that governing authorities find and appoint the most appropriate and professional members to the team. The appointment and selection of the most appropriate consultants for a particular project adds to the importance of the project, and is also a way in which to avoid planning mistakes (Section 3.8).

Consultant selection should foremost be characterized by an open and transparent process. Secondly, structuring the process of appointing consultants to be as competitive as possible ensures that the project developers have selected the most qualified team members at the most cost-effective rates. This may not always be the case, however, and particular care should be taken in the technical evaluation of consultants. It is critical that the technical abilities and experience of consultants match the vision and goal of the particular type of BRT system and the local context.

While designing an open, transparent, and competitive selection process may at first appear to be a time-consuming endeavor, this part of the project planning is fundamental to the future success of the project and, if dealt with correctly, can be relatively easy to implement.

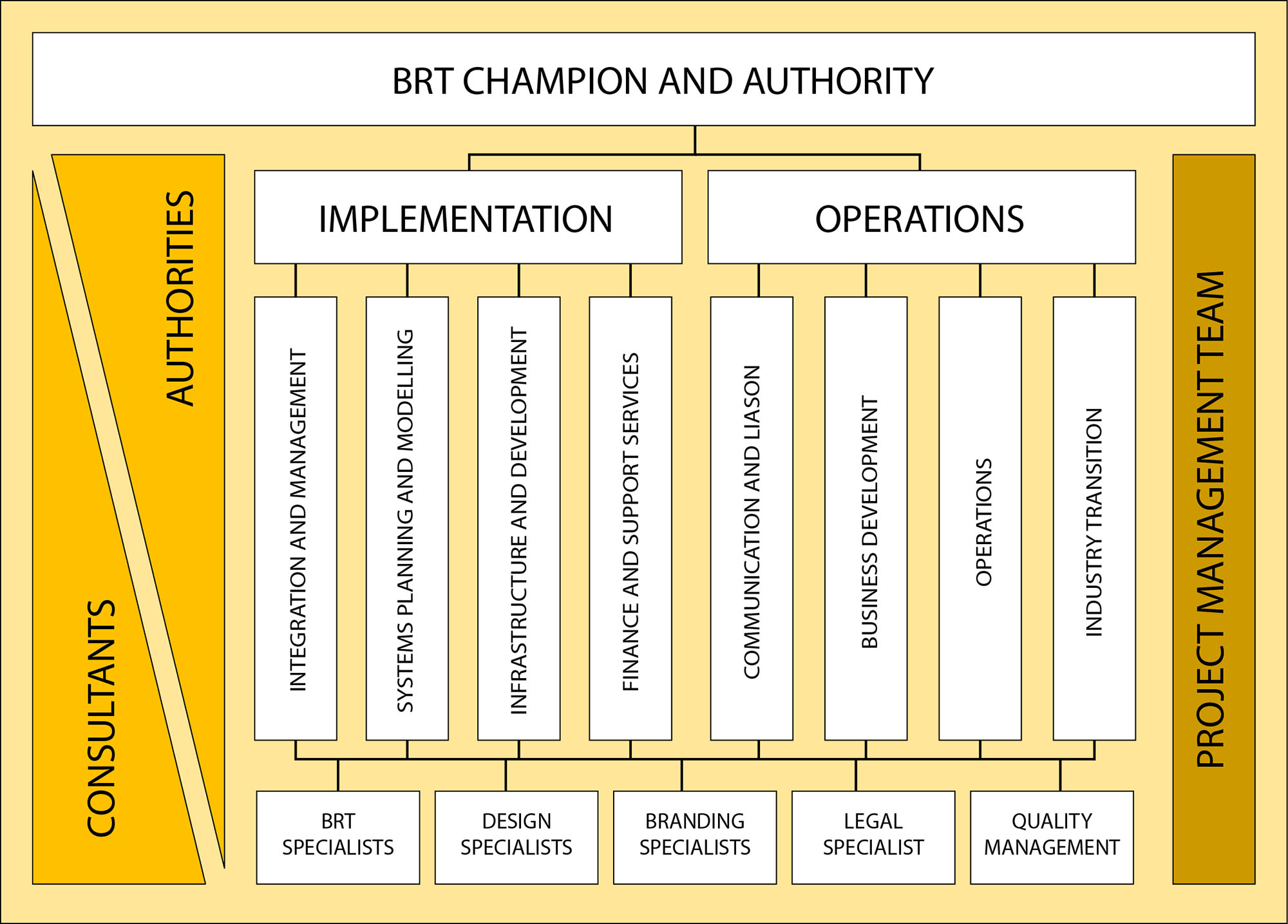

3.4.4Project Management Structure

Once the project is officially announced to the public, a clear project management structure should be firmly in place. While pre-project fact-finding activities may be sufficiently conducted with a few staff members and/or consultants, the formal project should be given a definitive personnel structure at the outset. The specific organizational structure will vary with local circumstances, but in all cases the structure should reflect the importance given to a new public transport system for the city.

Perhaps most important, the chief political official overseeing the project should be seen as the project champion. In most cases, this position should be held by the local political leader, while the hands-on oversight of the deliverables should be the responsibility of the political representative for transportation.

This type of direct leadership involvement could ensure that the project remains a political priority throughout the development process. Caution should, however, be taken that the project does not suffer from cross-party political manipulation or the merit of the system be lost through the association with only one political party.

The management structure of a BRT project will benefit from internal and external advisory committees or teams. The internal advisory committee usually consists of other local authorities or entities with some interest in or interface with the project. The external advisory committee would generally consist of key outside stakeholders, including national government representatives, trade and labor unions, commuter organizations, and local and international technical experts. Formal inclusion of all key stakeholders in the process can promote the necessary buy-in to make the project a reality. Giving voice and ownership roles to the various groups will ideally create a spirit of shared commitment that will carry the project toward implementation.

The inclusion of related agencies and departments, such as public works, transport, urban planning, finance, environment, and health in the steering committee could ensure cooperation. Furthermore, at some point the support and knowledge of these representatives could prove invaluable. Their inclusion could also limit the risk of future competition for budget allowances or priority, and facilitate interagency cooperation during the implementation of the BRT project.