3.3Procurement

Opportunity arises for the prepared mind.Louis Pasteur, chemist and microbiologist, 1822–1895

Once the commitment to the BRT project has been established through the political and statutory processes, the procurement of the technical and professional services for the project planning must commence. This procurement process will vary depending on the local protocols and the dictates of the funding sources. However, a transparent and legal process is not negotiable.

3.3.1Tendering and Contract Documentation

Often, the first step in any competitive tendering process is to issue a call for Expression of Interest (EOI). The EOI document basically requests that all firms and individuals interested in bidding on the project submit a document stating their interest. The EOI should be distributed as widely as possible to all potential consultants and firms. Since many consultants may have other commitments or interests, not all targeted firms will likely respond. The most knowledgeable consultants tend to gravitate to the projects with the best chance for success, and will need to be convinced that a particular project is worthwhile for them to invest the resources required for a bidding process. Simply sending out the EOI will generally not be sufficient, but this does remain a critical part of the process.

Furthermore, the EOI aids the relevant officials in developing a shortlist of potential consultants who may then be called on to submit more detailed proposals. The EOI process permits a wide range of consultants to extend their interest without the necessity of a lengthy and costly formal proposal.

The EOI document is usually basic and brief in composition, without unduly detailed contents. Any background information on the relevant city or the potential system concept may be available separately. Authorities should carefully consider the content provided, as this may prejudice quality teams against making a submission or offer undue guidance to teams, thereby stifling potential inventive approaches to the planning process.

Expressions of Interest should focus on gaining a clear understanding of the individual professionals in a team, rather than general information on the bidding companies, as a team consisting of a group of key, appropriately experienced individuals will benefit the planning process more than teams of generalist professionals in the related fields such as infrastructure or transportation. The EOI should be structured to gain maximum information on the key experts, rather than the track record of the firm.

As BRT has grown in popularity, the number of self-proclaimed BRT experts has also grown, and as much additional research as possible should be done into the qualifications of the specific team being proposed. The managing authority may even resort to interviewing some previous clients of the key consultants, establishing the reputation of the team members on earlier relevant projects. The international community of true BRT experts is unfortunately still very small. This does, however, simplify the process of vetting the submissions of a team submitting an EOI.

No specific principle exists on the number of teams to be invited to submit a formal tender from the EOI process. Although a large number of tenders may require a more complex evaluation process, this may offer the potential for a highly competitive process. Generally, the preference is to have only a manageable number of submissions to evaluate, limiting the effort and time associated with this phase of the process. Furthermore, requesting proposals from individuals and firms with limited or no experience, and with no chance of meeting the technical criteria required, can place undue strain on the authorities and the applicants. Thus, creating a shortlist of three to seven teams to ask for detailed proposals or tenders should provide a sufficient level of competition without becoming an unwieldy administrative burden.

The next phase of the contract procurement process may typically involve the development of Terms of Reference (TOR). Whereas the EOI sets a general framework for soliciting professional services, the TOR should detail the full requirements from which the detailed proposal will be developed. The TOR may not necessarily list every detailed action required, but should note the specific products and deliverables required. For example, the TOR may call for the delivery of specific plans, such as operational plans, infrastructure plans, architectural concepts, detailed engineering plans, financial plans, and marketing strategy plans, and will most likely include a detailed description of the requirements of the planning process. A well-crafted TOR will allow for the creative input from the professionals on the way in which these plans or results could be achieved.

The proposed project cost is usually the principal decision-making factor in awarding the project to a professional team. However, the importance of the relevant experience and qualifications of the team should never be ignored in the adjudication process. As most authorities are legally bound to award the contract to the lowest bid, and no mechanism is allowed to prequalify only teams with appropriate experience and technical abilities, the BRT project could suffer from the results of such an appointment.

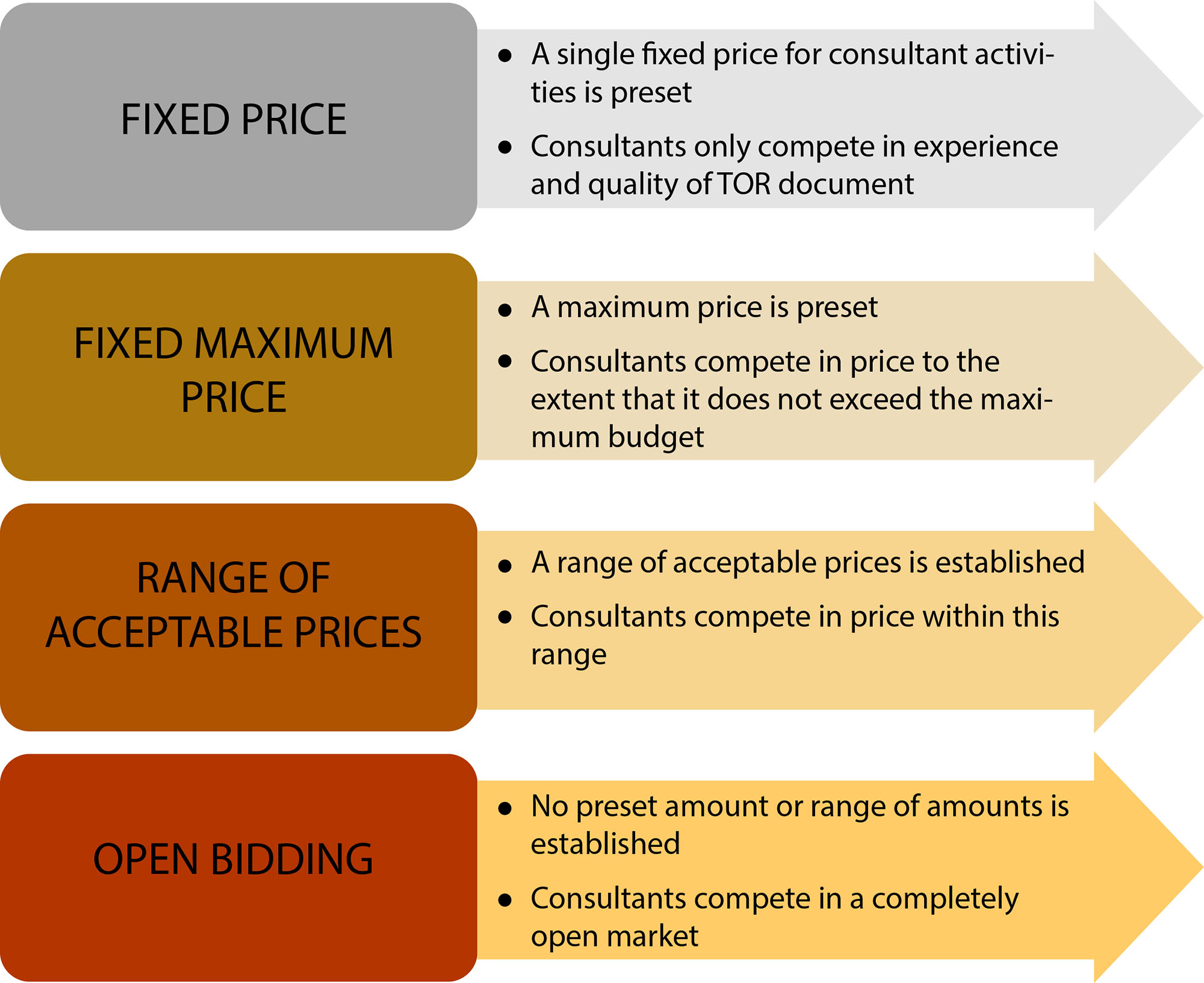

The particular mechanism by which bid adjudication and award could occur may depend on local legislation. Some authorities are legally bound to a fixed price system. But by introducing some degree of competitive price bidding, the authority will gain a better understanding of the differences between the competing firms or teams. Some cities may use a fixed maximum price or a range of acceptable prices in order to limit bids within the established or available budget. In such cases, all firms may simply bid the maximum amount or the median of the given range. Thus, any preset limits will tend to reduce the competition and may increase the actual costs over that which could be achieved in a truly competitive market.

An open bidding process could, by comparison, have several benefits. First, without preset limits, firms will tend to lower bids in order to effectively compete with others. Open bidding usually encourages innovation and creativity among the competing firms to find the most cost-effective way in which to deliver a quality plan. Second, the range of bids received provides feedback to the authority on the actual anticipated costs of the required product. With a preset value, firms will potentially adjust the team input levels and the quality applied to the final product in order to achieve the fixed budget. Third, open bidding makes it easier to distinguish between different bids. The likely spread of bid values provides a more discernible gauge to evaluate the proposals.

The risk associated with an open bidding system would be that all the firms bid an amount that exceeds the maximum allocation available to the authorities. This could result in program delay, as the authorities may need to secure additional funding or reconsider the scope of work to align this with the available funding. In some cases, this may even lead to starting the procurement process to align the budget with the project expectations from the start. Authorities may be advised to include a contract clause whereby the bidding process could be cancelled and the process started again from the beginning if the bidding prices are considered too high or not in keeping with a realistic expectation of the quality of the product required. This clause may also be invoked in circumstances where none of the bidding entities are sufficiently qualified to deliver the project products.

Some authorities may also be able to legally stipulate that bids may be excepted even if the price exceeds the (undisclosed) budget. Bids that exceed an undisclosed maximum may not necessarily be automatically disqualified. These TORs could specify that the bid price is not final, but a consideration along with the technical competence and other key factors in the selection of a winning bidder. An overbid may bring a penalty, but could add value to the end product if paired with key skills and competencies. At this point, the winning bidder may even be requested to submit a similar quality bid, but within the available budget.

In all of the above, it is essential to set quality criteria, as the risk exists that the lowest bid will be awarded, without the team having the expertise or qualifications to deliver the most basic of planning products. This will be elaborated on in section 3.8.

The decision-making process for both the EOI and the TOR must be confirmed and generally known before the procurement process starts. Ideally, the evaluation criteria should be created in an open and transparent manner, with input from a variety of sources, including contract or legal input to ensure that best procurement practices are followed and technical specialists to evaluate the content of the bid and the team experience. Placing the full decision-making control on one individual could create an unfavorable impression of the process and the project.

Clear and consistent decision making could benefit from a quantitative scoring system, while a process that favors only qualitative evaluations can be vulnerable to mismanagement. Should the evaluation criteria or decision-making process be considered questionable or objectionable by the unsuccessful teams, legal challenges could be lodged that would severely impact the project development.

As there is no commonly accepted definition of BRT and projects associated with the concept of BRT can vary significantly, it may be necessary to further qualify the type of BRT experience being sought, to ensure that the team with the most appropriate experience and qualifications is selected. Equally, the selection of a team or individuals that have sufficient BRT experience must be combined with clear local knowledge and understanding. This may be particularly useful in an example where the BRT system being planned is likely to require the restructuring of existing public transport routes, as opposed to a system that does not plan to alter existing routes, or in a local context with particular political challenges.

Despite the best efforts to clearly articulate the project objectives in the professional contracts, misunderstandings can arise. In such cases, consultants may work in a project direction that differs from the intent of the project initiators. By phasing the professional input, such misunderstandings can be corrected before a large amount of work is done. The phase approach essentially requires that consultants obtain approval from the relevant authorities prior to progressing to the next phase of the project. Rather than waiting until the final report is submitted to review the planning project, officials review intermediate findings and give their approval (or not!). Such project milestones should be explicitly stated in the professional contract or agreement at the time of procurement and appointment.

The above scenarios can be avoided by maintaining a close dialogue and working relationship with the consultant team and the relevant officials. Weekly, or even daily, engagements will continuously confirm the project’s direction and allow for adjustments as circumstances require. As an alternative, and particularly in cases where the local authority has very limited in-house resources, a separate team of process managers could be hired to act as agents in this regular engagement process.