10.6Focus Groups

I believe in accessibility. I believe in honesty and a culture that supports that. And you can’t have that if you’re not open to receiving feedback.Mindy Grossman, CEO of the Home Shopping Network (HSN), 1958 -

Focus groups can provide significant qualitative information quickly and in depth, based on a group discussion guided by an interviewer. A delicate science of complex interactions with ethical implications, focus groups should be facilitated by social science professionals to encourage full discussion among all participants, usually six to twelve people, and to provide useful data. A typical session lasts about two hours.

The main components to consider for any focus group, however, are:

- Participant selection: It is essential that participants be representative of the groups you are targeting with respect to ethnicity, age, income, and any other relevant factor in the local context;

- Rapport with group: It is important for whomever is guiding the discussion to establish a good rapport with the group, such that the group feels free to give their honest opinions on the topic;

- Mix of targeted and free questions: Participants should be guided toward providing the information needed, but also encouraged to speak freely, as they can introduce opinions and ideas that had not occurred to the group previously;

- Equality of attention: All individuals in a group should be heard. It is a good idea for moderators to give priority to those who have not spoken, to avoid a tendency for one or two outspoken individuals to dominate, or get into lengthy debates. Ground rules should be laid out in advance, explicitly to the whole group, and the group should acknowledge and accept them;

- Reports and conclusions: The focus group leader should provide an extensive data set on responses and analysis, including conclusions and suggestions for achieving communications goals;

- Knowledge of BRT: Ideally, the social science professionals involved should have experience with transport planning and know the specific BRT project well. Ideally, the team should include core project team members who have full and up-to-date information of the project;

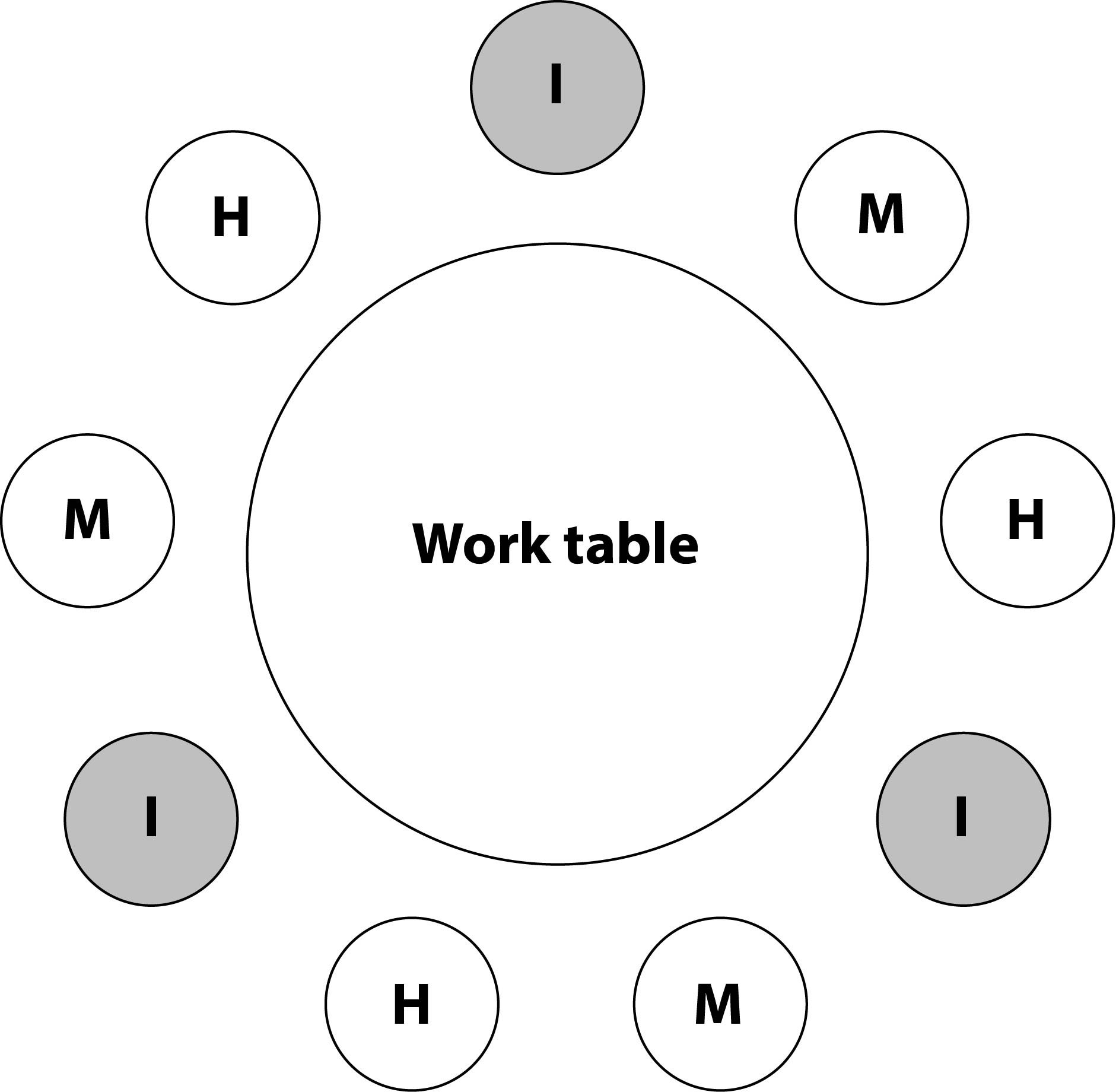

- Horizontal process: It is also essential that any communications process be handled as a horizontal process, where there is no expectation or indication of powerful and powerless actors. That is, meetings should not be held in a way that emphasizes or creates a sense of “the knowledgeable versus the ignorant” or “powerful versus powerless.” This includes such details as setup of tables, chairs, and in general an atmosphere of horizontality, with no differences in level between participants and group moderators.

10.6.1Committees

A particular form of the small group meeting, which usually lasts and evolves over a much longer period, is the advisory committee made up of civic, private, and government representatives. Committees have become so relevant to public transport planning in the United States that the Transportation Research Board (TRB) commissioned a specific study of how they function (Hull 2010). Key lessons included:

- Clear expectations about committee roles and responsibilities contribute to an advisory committee’s success;

- For committee membership, the need for representation of all viewpoints can be balanced with the need to maintain a manageable committee size;

- Agencies find value in the input provided by advisory committees and think of them as an indispensable part of the public involvement process;

- Many agencies employ professional public involvement staff to support committees and other outreach activities;

- Committee evaluation can lead to improved effectiveness (pp. 1-2, Hull 2010).

These committees may function at the regional or local level, on a project basis, or they may simply be standard practice for all aspects of public transport planning and operations, including monitoring contractor activities and financial incentives.

Training of members is an integral part of the process in most cases. Often a standing committee that functions at the regional level forms subcommittees to deal with specific projects. This permits greater precision, while still maintaining the panoramic view of the whole.

The TRB study identified several core characteristics of community-based advisory committees:

- Interest groups from the project study area are represented;

- Meetings are held regularly;

- Comments and participants’ points of view are recorded;

- Consensus on issues is sought, but not required;

- The committee is assigned an important role in the process;

- Representatives truly represent users and are accountable to them.

Often, governments or agencies think first of selecting people they feel comfortable with, but this is usually counterproductive and can undermine the benefits of participation. One way of selecting people to encourage a more representative, accountable advisory committee is to have interested groups and organizations register with the organizing body. These groups then nominate potential committee members, and vote to select them. Typically, highly respected individuals or organizations win many of these slots, as they would probably do in a situation where the authority selects them, but a vote-based system increases the legitimacy and therefore the credibility of advisory committee members.

The most effective committee representatives not only attend meetings and offer their opinions, but they also take what they have learned back to their community, group, or broader constituency for discussion and additional input. This helps spread the learning acquired through expanding networks of people and also expands the catchment area of the data/feedback received through participation. Clear articulation of their roles and good training can ensure that this happens.

Having participants who genuinely represent functioning organizations also improves results. Many neighborhood associations or federations have their own publications, for example, that can spread the word about new BRT programs more effectively than can an individual.

These kinds of participants function as information transmitters. They tend to be gatekeepers for particular communities: when they agree and support a policy, their credibility, won through years of work and immediacy, can greatly enhance acceptance throughout an entire territory

Advisory committees must have demonstrable impact on BRT decision making. It is no good trying to win women cyclists’ support for BRT, for example, if suggestions to include cycle parking at key stations or permit cycles on vehicles during off-peak hours are never formally integrated into projects. If committee members see integration of at least some of the ideas they put forth, they are more likely to believe in and support the participatory process.

10.6.2Civil Society Organizations

Building civil society organizations is a complex task that largely falls outside the mandate of BRT initiatives. Nonetheless, it can be the single most relevant factor in generating strong political support for an existing or new BRT system. BRT initiators should learn as much as possible about the civil society environment in which their projects are located and make an effort to ensure that their project is functioning optimally.

In practical terms, this means ensuring solid communication, especially with neighborhood or other citizens’ organizations, providing training to improve the knowledge of BRT, and planning charettes or other kinds of activities that effectively integrate proposals for improvements. Incorporating skilled citizen representatives (neighborhood leaders familiar with the various issues surrounding BRT) can greatly enhance effectiveness and build a sense of mutual respect and solidarity among different system players who might otherwise generate considerable friction.

Civil society representatives should be included in advisory committees of the BRT agencies, if they exist, and should also be involved in additional activities, such as visiting other BRT systems around the globe. One of the ways that cities and countries have found to do this with regard to other sustainable transport modes, particularly walking and cycling, is to earmark funds that encourage civil society development in general and/or specifically for neighborhood associations. These funds enable NGOs to develop studies, training, education, and other programs; to support corporate social responsibility initiatives; and to coordinate with other funders to make focus on transport-related issues part of the criteria for awarding funds.

10.6.3Engaging Local Networks

While the above processes all offer opportunities for interested members of the public to engage with the planning process, having a truly representative public participation process also requires proactively endeavoring to meet people where they live, work, and play.

Proactive or collaborative engagement can take many forms: attending festivals, farmers markets, local fairs, flea markets, or other special events; speaking at community organizations, resident or business associations, or clubs; engaging the public at public transport centers, malls, and other gathering places; canvassing neighborhoods; engaging elected officials; or partnering with other agencies, organizations, institutions, or places of worship. The concept is to take the message of the agency directly to the public and broaden the number and diversity of people reached by using established local communication and support networks. This type of engagement offers agencies the chance to interact directly with their customers, learn about neighborhoods, and build relationships for future outreach.

One example of proactive engagement that has been particularly useful in other planning processes and before the system has been launched involves installing a prototype station in areas of heavy pedestrian traffic. This allows users to familiarize themselves with the BRT concept in advance and also generates excitement for the new system. In Ahmedabad, India, the city built a sample station a year before operations began on the Janmarg BRT. The prototype allowed the city to showcase the station design and help educate the public about how it would operate. At the same time, the prototype allowed the city to test and tweak certain design elements.

In Bogotá, the city used a program known as “Mission Bogotá” to reach out directly to members of the public. The city trained and employed more than three hundred young people from low-income communities as “ambassadors” for the proposed system. The campaign began six months before the city’s BRT TransMilenio started up and took place mainly at bus stations and on board regular buses, along with civic gathering places and local schools. The outreach team of Mission Bogotá would discuss the project directly with the public and personally answer any questions or concerns. Many cities now use these techniques to impart transport information in a friendly, lighthearted manner.

Online Engagement

Public transport agencies have embraced the Internet as a means of communication with the public since the 1990s. Internet-based communication can be broken down into two phases. The initial phase was dominated by one-way communication, where agency websites were geared primarily toward marketing their services online, much like an online brochure. These websites allowed customers to retrieve information such as maps, schedules, guides, and fare information, but provided little opportunity for interactivity (Morris et al., 2010). Today, websites are more interactive. Project websites routinely offer customers the ability to submit comments. In some cases these comments are shared on a discussion board or blog. For its 2035 long-range plan update, the Virginia, USA, DOT developed a web-based workshop to mirror the information and interactive opportunities available at its in-person meetings held throughout the state. The convenience afforded by the Internet in allowing users to participate from the location and time of their choosing helped push online participation above the total combined participation at all of the in-person meetings (VTrans2035).

Box 10.1 Example: Showcasing Janmarg

The Ahmedabad, India, Janmarg BRT was very successful with proactive engagement in the lead-up to the launch of the system in 2010. The Janmarg communications team took advantage of many options to showcase the system by developing and displaying prototypes and offering free trial rides over an extended period of time. This made it easy for people to become familiar with how to use the system. It also alerted systems planners to user-interface problems, giving them a chance to resolve these issues before customers started paying for their rides, thereby heading off many potential public relations problems before they began.

The rise of social media tools and mobile phone and tablet applications offers a host of options for multi-directional communications, reaching people in their preferred way of receiving and interacting with information.

Many public transport providers have discovered the benefits that social media offers for public participation. It also allows direct communication in real-time and unfiltered by the media, which can help foster an interactive dialogue with the public (Eirikis and Eirikis 2010). Social media can provide an easy and accessible forum for public participation, but it should be used to supplement, rather than replace, other more personal options for participation. Although it may be easy to solicit feedback on Twitter, the responses you receive are very unlikely to represent an accurate sample of your population. (See more about social media in Chapter 9: Strategic Planning for Communications.)