10.2Industry Standards of Practice

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them...well, I have others.Julius Henry "Groucho" Marx, comedian and actor, 1890 - 1977

Public participation strategies are as diverse as the communities, locations, and agencies they serve. Specific public involvement techniques and the methods by which public transport providers execute public involvement strategies are constantly evolving. There are, however, some overall generalizations about the elements of agency public participation strategies and the process for creating them.

Although this chapter focuses primarily on agency-government-user/civil society interactions, the principles of participation outlined here apply to other stakeholders including operators and drivers (addressed more comprehensively in Chapter 16: Vehicle Operator Contracting and Industry Transition).

Governments, private sector, and civil society actors have diverse and sometimes contradictory views of what citizen participation in urban transport planning should be. Maximizing success in participation requires a fundamental shift from viewing public engagement and participation as an obligation to understanding it as an opportunity to improve and build the short- and long-term viability of the system. A well-designed participatory process can also strengthen the long-term credibility and viability of organizations that build civil society.

10.2.1Goals and Objectives

Just as in communications planning, goals and objectives play a key role in public involvement strategies. They guide the entire process, influencing who will be engaged, the level of participation desired, the type of information that will be needed, and the techniques to be used. Goals and objectives also set expectations about what the public participation effort will achieve and provide a basis for measuring outcomes.

The goals themselves should be based on the specific needs of the project. What are the questions that need to be answered? What are the missing pieces of information? What type of public buy-in is desired? Below are common project-specific goals from the International Association of Public Participation.

- Inform: To provide the public with balanced objective information to assist them in understanding the problems, alternatives, opportunities, and/or solutions;

- Consult: To obtain feedback on analysis of alternatives and/or decisions;

- Involve: To work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered;

- Collaborate: To partner with the public in each aspect of the decision, including the development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution;

- Empower: To place final decision making in the hands of the public (IAP2 2010). As with communications planning, each goal should be followed by specific, measurable objectives. For more information on defining goals and objectives, see Chapter 9: Strategic Planning for Communications.

10.2.2Principles of Participation

An essential part of having a well-designed participatory process is setting clearly defined principles that all participants agree to abide by, which are enforced by leaders or coordinators of participant groups. The Community Development Society () suggests the following five principles of good practice in community development:

- Promote active and representative participation toward enabling all community members to meaningfully influence the decisions that affect their lives.

- Engage community members in learning about and understanding community issues, and the economic, social, environmental, political, psychological, and other impacts associated with alternative courses of action.

- Incorporate the diverse interests and cultures of the community in the community development process; and disengage from support of any effort that is likely to adversely affect the disadvantaged members of a community.

- Work actively to enhance the leadership capacity of community members, leaders, and groups within the community (so that they may be ambassadors for BRT).

- Be open to using the full range of action strategies to work toward the long-term sustainability and well-being of the community.

There are many versions of these good practice principles, and they may be adjusted for local context and to address specific concerns.

10.2.3The Passive vs. Active Approach

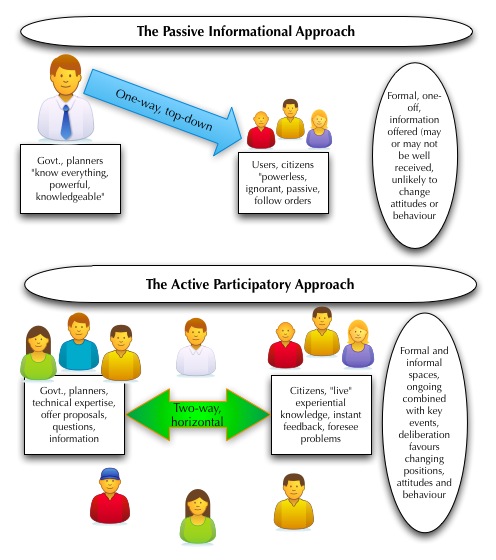

In the past, agencies have offered suggestion boxes, toll-free telephone numbers, leaflets, or advertising campaigns as examples of “participation.” While these offerings are not without value—high-quality collateral and information is a precondition for participation—they do not constitute a participatory process.

Public transport providers must often make complex decisions about the type and amount of information to provide to the public, balancing the risks of providing too little information and too much. This can be further complicated by the often technical nature of the data and the risks of it being confusing or misinterpreted. However, information sharing is important not just for meaningful public involvement, but also for building trust within the community, creating transparency at the agency, enhancing advocacy efforts, and proactively guiding the public conversation instead of allowing others (including the media or other stakeholders) to dominate the debate.

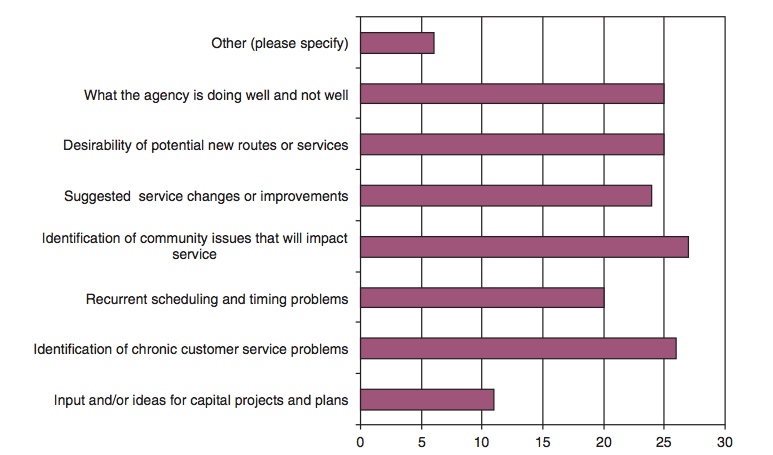

Equally important for shaping the public involvement process is the agency’s determination of what information it wants from the public. The survey results support the idea that for public transport providers, public involvement provides the agency with critical missing information. When asked about the type of input agencies typically want from the public, respondents noted that they want to know about community issues that might impact public transport service, as well as chronic customer service problems.

Informational campaigns take place along a spectrum. At one end, you have one-way communication, which means providing information, usually to a broad public with no ability to receive feedback from the audience. This is what is known as a “passive approach.” Further along the spectrum are limited two-way communications processes, such as feedback surveys or Internet voting on preferences, which tend to be more sophisticated and have more of an impact on people’s thinking, although usually not on their behavior. At the other end, you have a genuine participation process or an “active approach” that involves more complex two-way or multi-directional communication, usually referred to as deliberation.

Generally speaking, the more active the approach, the better the results. For example, in deliberation, groups are engaged in an intense form of facilitated communication meant to bring crucial information to the surface, including the participants’ knowledge, interests, feelings, and fears. In the urban sphere, deliberation occurs in formal or informal spaces as preferred so people can hammer out agreements in a more relaxed, trusting environment. It can involve being active in the spaces being planned by conducting walking, cycling, or neighborhood access audits and reviews. This should happen in planning phases and be facilitated by the BRT team in conjunction with community groups. A well-organized participation process can transform people’s thinking and, more important, their actions.