7.6Optimizing the Station-to-Vehicle Interface

Let every man praise the bridge that carries him over.English proverb

Besides increasing the vehicle size, frequency, and number of sub-stops, there are several elements of the station-to-vehicle interface that can be improved to reduce boarding and alighting times, therefore reducing station saturation and increasing corridor capacity.

7.6.1Platform-Level Boarding

To reduce boarding and alighting times, most state-of-the-art BRT systems have introduced platform-level boarding. With platform-level boarding, the docking bay platform is designed to be the same height as the vehicle floor. Besides fast boarding and alighting, it also allows easier access for persons in wheelchairs, parents with strollers, young children, and the elderly.

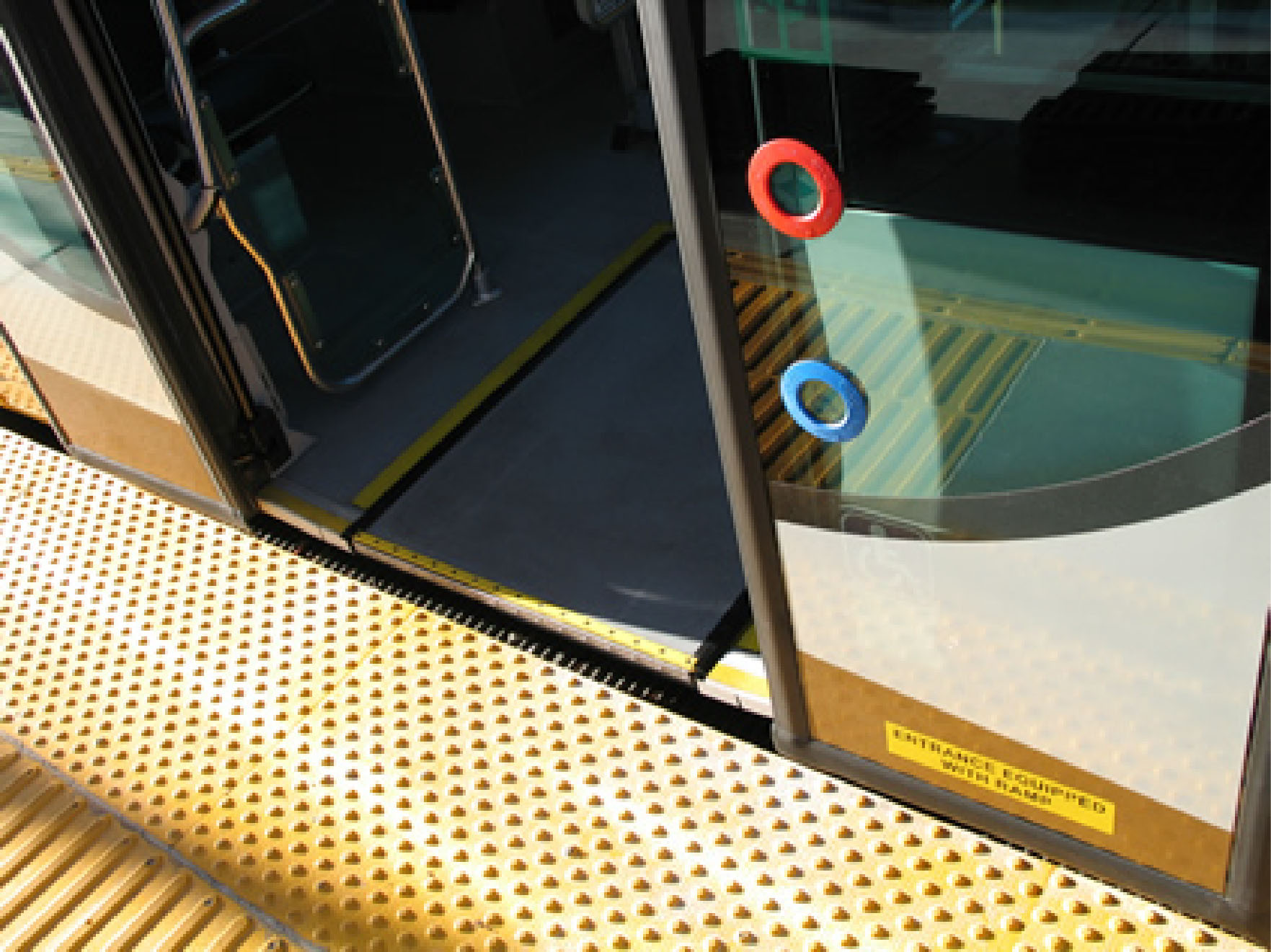

There are currently two different types of platform-level boarding techniques. In one case, a gap exists between the platform and the vehicle. The gap may range from approximately 4 to 10 centimeters, depending on the accuracy of the vehicle-alignment process (Figures 7.20 and 7.21). Such a boarding gap is comparable to or smaller than the gap present on many rail-based systems. Alternatively, a vehicle can employ a boarding bridge that physically connects the vehicle to the platform, thereby eliminating the gap completely. The boarding bridge consists of a flip-down ramp that is attached to the vehicle’s doors or one that extends from the bus upon docking. As the doors open, the boarding bridge is released and covers the gap between the vehicle and the platform (Figures 7.22 and 7.23).

Both techniques, gap entry and boarding bridge entry, have their advantages and disadvantages. Cities such as Curitiba and Quito have experienced much success with boarding bridges. A typical boarding bridge is 40 to 50 centimeters in width, meaning that the vehicle only needs to align within about 35 to 45 centimeters of the platform (Figure 7.24). Thus, there is much more room for error using the boarding bridge.

The boarding bridge also provides boarding and alighting customers with greater confidence in placing their steps. The confidence means that customers will not have to look down at a gap to judge safe foot placement. Instead, customers confidently march forward. The small act of looking down slows each person’s boarding and alighting time. While this lost time seems small on a per customer basis, the cumulative effect across all customers can be significant. The added customer confidence with the boarding bridge also means that two people can board or alight side by side. When a gap is present, customers are less likely to board simultaneously. The uncertainty imposed by a gap means customers are less likely to handle both the placement of the foot and the distance beside another customer at the interface point. A boarding bridge also is significantly more user-friendly to customers with physical disabilities, wheelchairs, and strollers.

Despite these benefits, the boarding bridge does bring with it a few disadvantages. The added cost of the boarding plate and the pneumatic system to operate it entails a modest increase in vehicle costs, as well as an increase in maintenance costs. As a moving part, the boarding bridge also introduces additional maintenance issues and the potential for malfunction. There is also one aspect of the boarding bridge that does not hold a time advantage. The deployment of the bridge itself takes about 1.5 seconds. Likewise, the retrieval of the boarding bridge at departure also requires about 1.5 seconds. While this deployment and retrieval roughly coincide with the opening and closing of the doors, they introduce a slight delay to the boarding and alighting process. However, the overall efficiency advantages of the boarding bridge tend to compensate for the deployment and retrieval time.

7.6.2Fare Collection

In many conventional bus services, the driver is responsible for the collection of fares, as well as driving the vehicle, and customers are only allowed to enter through the front door. Thus, on-board fare collection means that boarding time is largely determined by the fare collection activity. If the fare collection process is slow, the whole public transport service is slow. Typically, customers take from two to four seconds just to pay the driver. If drivers also need to give customers change manually, this increases to fifteen seconds. Once customer flows reach a certain point, the delays and time loss associated with on-board fare collection become a significant system liability.

Most BRT systems since Curitiba have instituted external or off-board fare collection and fare verification. Customers pay their fare prior to entering the station, and then have their fare verified as they pass the entry turnstile or gate. Boarding and alighting can happen from all doors at once, and there is no delay in boarding and alighting related to the fare collection and fare verification. Pre-board fare collection and verification can reduce boarding times from 3 seconds per customer to 0.3 seconds per customer. In turn, the reduction in station dwell time greatly reduces vehicle congestion at the docking bay.

The introduction of contactless smart cards and other modern payment systems can reduce on-board payment to two seconds per customer. Systems such as the Seoul busway make use of on-board fare collection using smart card technology. However, any time the driver is responsible for verifying fares, the speed of the service will be highly compromised, particularly if there is a large volume of customers. In the case of the Seoul busway system, customers must remember to swipe their smart cards both upon entering and exiting the vehicle. Delays can occur simply if a person enters the vehicle and must search through his or her belongings to find the fare card.

In some cities, on-board collecting devices have been installed at all doors, and the average time for boarding and alighting has been reduced further. On the Geary Boulevard corridor in San Francisco, USA, the boarding times are 1.2 seconds per customer. However, these times are still several times higher than boarding times for systems with off-board fare collection.

In some bus systems, conductors sell tickets on board. While such an arrangement allows customers to board quickly and then pay once the vehicle is moving, it may introduce other forms of delay. For example, in some bus systems in India, it is common for the driver to halt the bus to make sure the conductor has finished selling tickets to all of the customers on the bus before it reaches the next stop.

In addition, if the conductor remains in a fixed position on the bus, and boarding happens through multiple doors, customers must make their way to the conductor, a potentially unpleasant ordeal if the vehicle is crowded. Some systems employ a reservoir area within the vehicle to hold customers while they go through the fare payment and verification process (Figure 7.28) at a turnstile. However, in this technique, the boarding is just through one door that is always less efficient than all-door boarding, especially when using large buses. In Brazil, the reservoir area is commonly small to prevent fare evasion (by getting off the bus through the same door). The first three or four customers need one second to board; the remaining need three to five seconds.

With on-board fare collection and verification, alighting is usually faster than boarding. Typically, alighting times are approximately 70 percent of boarding times. In the case of off-board fare collection and verification, when vehicles are not crowded, there is no significant difference between boarding and alighting times.

Another method to avoid on-board fare collection and reduce boarding delays is to employ a proof-of-payment; customers must validate their own tickets that they purchase at shops and kiosks. Enforcement is then the responsibility of the police or contracted security personnel. Many European light rail systems utilize such a system.

Off-board payment collection is not necessarily the only way to reduce boarding and alighting times, but there are institutional reasons why this approach is generally more successful in the developing-country context. In particular, off-board fare collection and verification enhances the transparency of the process of collecting the fare revenues. When customers pay on board, and do not have to pass through a turnstile, there is no clear count of how many customers boarded the vehicle. Off-board fare sales to a third party make it easier to separate the fare collection process from bus operations. By having an open and transparent fare collection system, there is less opportunity for circumstances in which individuals withhold funds. This separation of responsibilities has regulatory and operational advantages that are discussed in more detail below. Further, by removing the handling of cash on board, incidents of on-board robbery are reduced.

Off-board payment also facilitates seamless transfers within the system. In addition, enclosed, controlled stations give the system another level of security, as security personnel can better protect the stations, thus discouraging theft and other undesirable activities. Off-board payment is also more comfortable than juggling change within a moving vehicle.

The main disadvantage to off-board fare collection is the need to construct and operate off-board fare facilities. Fare vending machines, fare sales booths, fare verification devices, and turnstiles all require both investment and physical space. In a BRT system with limited physical space for stations in a center median, accommodating the fare collection and verification infrastructure can be a challenge.

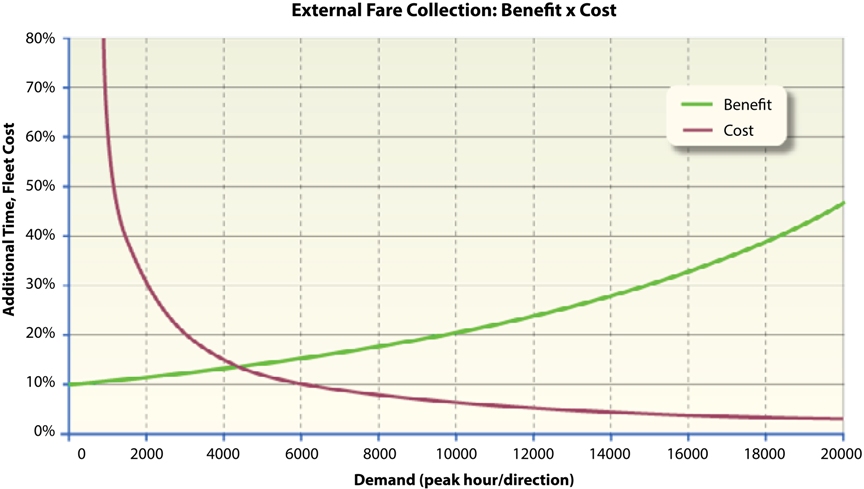

There is no one precise point at which a system’s capacity will determine if on-board or off-board fare collection is more cost effective. Much depends on demand figures from individual stations, physical configurations of stations, and average labor costs. However, the advantage of off-board payment clearly increases as the level of boardings and alightings at the station increases and is part of the BRT basics of The BRT Standard. In Goiânia, Brazil, the local public transport agency estimates that an off-board fare system is cost justified when the system capacity reaches 2,500 pphpd. The development of a cost-benefit analysis may help determine this capacity point, provided the data is available. Figure 7.29 provides an example of this type of analysis.

7.6.3Doorways

All the efforts applied to vehicle size, station design, and fare collection can be in vain if the vehicle’s doorways inhibit smooth customer flows. With too few doors, systems experience bottlenecks due to conflicts between entering and exiting customers that increase the total boarding and alighting time.

The most successful BRT systems have employed multiple wide doorways dispersed along the length of the vehicle to ensure that platform bottlenecks are avoided. Having multiple wide doors accounts for a total of 3 points in The BRT Standard. These systems provide at least two separate sets of doors on 12-meter vehicles and three separate doors on 18-meter articulated vehicles. Each double door should be at least 1 meter wide, allowing two people to enter or exit the vehicle simultaneously. Table 7.13 compares observed boarding and alighting times for different combinations of doorway and platform configurations.

Table 7.13Observed Boarding and Alighting Times for Different Configurations

| Configuration characteristics | Boarding and alighting times | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fare collection method | Doorway width (meters) | Stairway boarding or level boarding | Vehicle floor height | Observed; boarding time; | Observed alighting time |

| On-board, manually by driver | 0.6 | Stairway | High | 3.01 | NA |

| On-board, contactless smart card (no turnstile) | 0.6 | Stairway | High | 2.02 | NA |

| Off-board | 0.6 | Stairway | High | 23 | 1.53 |

| Off-board | 0.6 | Stairway | Low | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Off-board | 1.1 | Stairway | High | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Off-board | 1.1 | Stairway | Low | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Off-board | 1.1 | Level | High | 0.751 | 0.51 |

1. Colombia, Mexico

2. China

3. Brazil

NA – Not available

Doorway efficiency can also be closely tied to the interior design of the vehicle. The arrangement of the vehicle interior should provide adequate circulation space near the doors. In addition, some systems attempt to mitigate the conflict between boarding and alighting customers by designating some doorways as entry only and others as exit only. Curitiba utilizes this technique in some of its stations. This directional designation can improve boarding and alighting efficiency, but it can also cause customer confusion unless doorways are clearly marked.

The initial design of the Jakarta BRT system limited the system’s capacity due to the decision to utilize only a single doorway for both boarding and alighting. As a solution to its capacity constraints, TransJakarta elected to increase its vehicle fleet. However, only a small number of the additional vehicles actually helped increase capacity before vehicle queuing at the stations dropped the level of service down to unacceptable levels. Table 7.14 presents potential solutions to TransJakarta’s capacity problems. Shifting toward an articulated vehicle with multiple wide doorways would add the most capacity to the existing system, the analysis showed. TransJakarta has subsequently retrofitted stations and buses with additional doors and purchased larger vehicles.

Table 7.14Scenarios for Improving TransJakarta’s Capacity

| Scenario | Average boarding time (seconds) | Dwell time (seconds) | Average speed (kph) | Capacity (pphpd) | Required fleet size (vehicles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present situation | 2.5 | 45 | 17 | 2,700 | 60 |

| Improving boarding | 1.7 | 35 | 19 | 3,700 | 56 |

| Vehicle with 2 doors | 0.5 | 22 | 21 | 6,000 | 51 |

| Articulated vehicle with 4 doors | 0.3 | 18 | 23 | 9,600 | 26 |

Source: ITDP, 2006

7.6.4Vehicle Acceleration and Deceleration

The time required for a vehicle to approach and then accelerate away from a docking bay also has an impact on station saturation and system speeds. If conditions require a slow, careful approach to the stations, overall speeds and travel times will suffer. The time consumed in the deceleration and acceleration process is affected by the following factors:

- Type of vehicle-platform interface;

- Use of docking technology;

- Vehicle weight and engine capacity;

- Type of road surface;

- Presence of nearby at-grade pedestrian crossings.

The vehicle deceleration time is greatly influenced by the closeness in docking required. Manual alignment generates variability in docking distances that can be improved somewhat through the use of optical targets for drivers along the face of the station. Mirrors can also improve the accuracy of manual targeting. Some other ways to help alignment include Kassel kerbs and flexible rubber lining the platform that allow the bus to come close to the station without damaging the bus or the station. All of the largest BRT systems in the world use manual alignment.

Alternatively, there are automatic docking technologies that try to increase the speed and accuracy of vehicle-to-platform alignment. Mechanical, optical, and magnetic docking technologies can all be applied for this purpose. In each of these cases, the vehicle is automatically guided into platform position without any intervention from the driver.

Mechanical guideway systems, such as those utilized in Adelaide, Australia; Essen, Germany; Leeds, England; and Nagoya, Japan, physically align the vehicle to the station through a fixed roller attached to the vehicle. In these cities, the fixed guideway is utilized both at stations and along the busway. However, a city could elect to only utilize the mechanical guidance at stations.

Optical docking systems operate through the interaction between an on-board camera and a visual indicator embedded in the busway. Software within the on-board guidance system then facilitates the automated steering of the vehicle. The Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, MAX system has attempted to make use of this type of technology (Figure 7.31). Problems have occurred, though, due to the inability of the optical reader to function properly when the roadway is wet.

A magnetic guidance system works on a similar principle to that of an optical system, but with magnetic materials placed in the roadway as the location indicator. The Philaeus bus, as utilized in the Eindhoven, Netherlands, BRT system, is capable of magnetic guidance.

Optical and magnetic guidance systems produce a highly precise degree of docking. However, due to current limitations with these technologies and their software, required deceleration and acceleration speeds can actually be slightly less than manual techniques. Further, the added hardware and software costs of an optically automated system can push vehicle costs well over US$1 million each.

7.6.5Station Platform

The size and layout of the station platform will have a discernible impact on system capacity and efficiency. In some systems, platform size can even be the principal constraint on overall capacity. For many of the London Tube lines, it is the relatively small platform width that ultimately determines the total possible customer volumes.

The determination of the optimum platform size is based on the number of customers waiting to board and alight. If the platform hosts two service directions along one another, then the sum capacity requirements of both directions must be factored into platform sizing. Chapter 25: Stations details the calculation of platform sizing.