33.2Defining TOD

Development has become something to be opposed, instead of welcomed; people move out to the suburbs to make their lives, only to find they are playing leapfrog with bulldozers. They long for amenities that are not eyesores, just as they long to give their kids the experience of a meadow, that child’s paradise, left standing at the end of a street. Many communities have no sidewalks, and nowhere to walk to, which is bad for public safety, as well as for our nation’s physical health. It has become impossible in such settings for neighbors to greet one another on the street, or for kids to walk to their own nearby schools. A gallon of gas can be used up just driving to get a gallon of milk. All of these add up to more stress for already overstressed family lives.Al Gore, former United States Vice President, 1948-

TOD Defined

TOD is land development that is specifically designed to integrate, work with, and prioritize the use of public transport for daily urban mobility needs. Mere closeness to public transport stations is not sufficient for a development to qualify. TOD specifically denotes a proactive orientation towards public transport through particular land use and design characteristics known to facilitate and prioritize walking, cycling, and other non-motorized and intermediary modes of access to the stations. Key attributes of TOD include the optimized development intensity and land-use mix within the walkable zone around the public transport stations; a complete, easily accessed, well-connected, and well-protected system of walkways; safe cycling and secure cycle parking conditions; and the minimization of the impact of vehicular traffic and parking. When synthesized through high quality design, these elements have been proven to result in attractive and successful urban forms, where access to public transport is short, easy, pleasant, and safe, and eventually, the public transport supports a high and sustained ridership at stations (Europe’s Vibrant New Low Car(bon) Communities, ITDP).

Research in both developed and developing countries shows that the combination of raised density, mixed land use, street connectivity, and walkability improvements reduces automobile travel and increases both non-motorized and public transport travel per capita. (Kenworthy and Laube, 1999; Ewing, Pendall and Chen, 2002; Mindali, Raveh and Salomon, 2004; and Litman, 2004). For example, residents of the most urbanized neighborhoods in Portland, Oregon, USA, have been shown to use public transport about eight times as much, walk six times as much, and drive only about half as much as residents of the least urban areas.

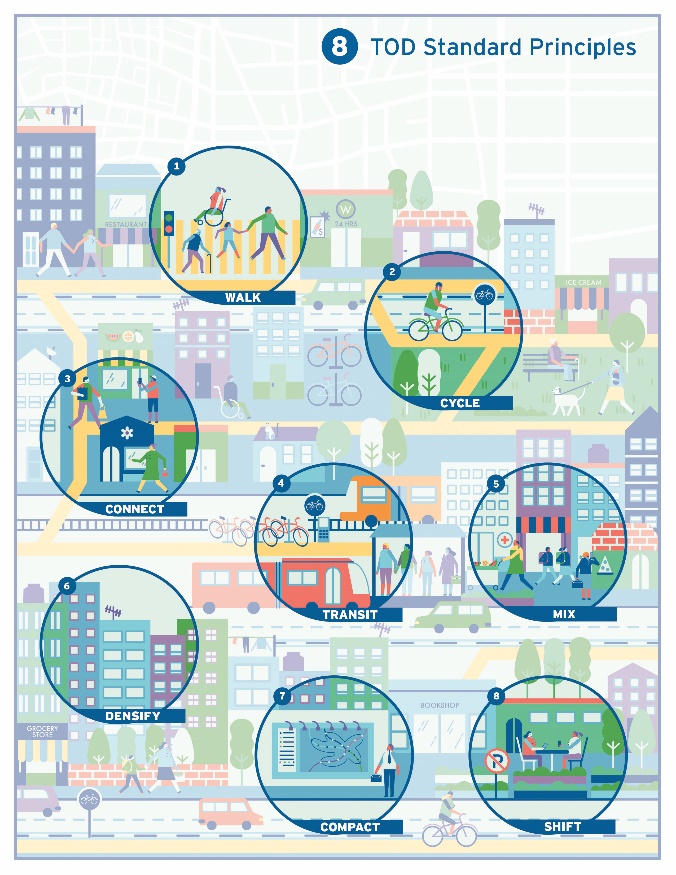

In order to understand relationship between transport and the urban environment, some basic principles were needed to explain on what this intersection depends. ITDP distilled eight basic principles of sustainable and equitable transport in urban life which form the core definition of TOD (Our Cities Ourselves: Principles for Transport in Urban Life, ITDP):

Eight basic principles of sustainable and equitable transport in urban life:

[WALK] - Develop neighborhoods that promote walking

[CYCLE] - Prioritize non-motorized transport networks

[CONNECT] - Create dense networks of streets and paths

[TRANSIT] - Locate development near high-quality public transport

[MIX] - Plan for mixed use

[DENSIFY] - Optimize density and transit capacity

[COMPACT] - Create regions with short commutes

[SHIFT] - Shift away from car dependency and increase mobility by regulating the use and reducing the supply of parking and roadway space.

Those principles form the foundation, but still were not enough to understand what this meant in practice. To give meaning to what those principles were supposed to achieve and what were the key criteria to achieving those, ITDP further developed those principles into The TOD Standard, which elaborates a set of key performance objectives that are essential to the materialization of these principles, along with a series of measurable performance indicators, or metrics, and a scorecard. This can then be used to assess plans and designs, station areas, and understand how well a neighborhood or a development is doing when creating inclusive transit-oriented and people-oriented places.

Slightly adapted excerpts from the TOD Standard introduce the principles and performance objectives system that follow in this section. Refer to the original publication for details on metrics and the scorecard (www.todstandard.org).

33.2.1Principle 1 | WALK | Develop neighborhoods that promote walking

Walking is the most natural, healthful, clean, efficient, affordable, and inclusive mode of travel to destinations within short distances, and it is a necessary component of virtually every transit trip. As such, walking is the foundation for sustainable and equitable access and mobility in a city. Restoring it or maintaining it as the primary mode of travel is pivotal to the success of inclusive TOD.

Walking is also potentially the most enjoyable, safe, and productive way of getting around, if paths and streets are attractive, populated, secure, uninterrupted, well protected from vehicular traffic, and if useful services and destinations are conveniently located along the way.

Walking requires moderate physical efforts that are beneficial for most people within reasonable distances but can be challenging or infeasible to some when body ability combines with obstacles, steps, or steep ramps to form barriers. In the TOD Standard, the terms “walking” and “walkability” should always be understood to be inclusive of users of walking or carrying aids, such as wheelchairs, white canes, baby strollers, and shopping carts. Complete walkways and crossings must fully support all users in compliance with locally applicable or international standards.

Objective A: The pedestrian network is safe, complete, and accessible to all

The most basic feature of urban walkability and inclusivity is the existence of a complete, continuous, and safe walkway network including safe crossings at desire lines that links origins and destinations together and to the local public transit station. The network must be accessible to all persons, including older people and people with disabilities, and well protected from motor vehicles.

Objective B: The pedestrian realm is active and vibrant

Activity feeds activity. Walking is attractive and secure and can be highly productive when sidewalks are populated, animated, and lined with useful ground-floor activities and services, such as storefront retail and restaurants. In turn, high foot traffic increases the exposure of local retail outlets and services and improves the vitality of the local economy. Visual interior–exterior interactions promote security in the pedestrian realm through passive and informal observation and surveillance. All types of land uses are relevant to street activation and informal observation—not only shops and restaurants but also informal vending, workplaces and residences.

Objective C: The pedestrian realm is temperate and comfortable

The general willingness to walk, and the inclusion of people of all bodily abilities, can be significantly improved by the provision of shade and other forms of shelter from harsh climate conditions—such as street trees, arcades and awnings—or by street orientation that mitigates sun, wind, dust, rain, and snow exposure. Trees are the simplest, most effective, and most durable way of providing shade in most climates, and they have well-documented environmental and psychological co-benefits. Highly recommended, but not measured in this standard, for the sake of simplicity, are amenities such as benches, public toilets, drinking fountains, pedestrian-oriented lighting design, wayfinding signage, landscaping, and other street furniture and streetscape-enhancing elements.

33.2.2Principle 2 | CYCLE | Prioritize nonmotorized transport networks

Cycling is one of the most healthful, affordable, and inclusive mode of urban mobility. It combines the convenience of door-to-door travel and the route and schedule flexibility of walking with ranges and speeds that compare to or surpass local transit services. Bicycles and other means of people-powered transport, such as pedicabs, also activate streets and greatly increase the ridership catchment area of transit stations. They are highly efficient and consume little space and few resources. Cycling friendliness is therefore a fundamental principle of TOD. Cyclists, however, need protection as they are among the road users most vulnerable to crashes with vehicular traffic. Their bicycles are also vulnerable to theft and vandalism and require secure parking and storage. The key factors in promoting cycling are thus the provision of safe street conditions for cycling and the availability of secure cycle parking and storage at all trip origins and destinations and at transit stations.

Objective A: The cycling network is safe and complete

A safe cycling network connecting all buildings and destinations by the shortest routes available is a basic TOD requirement. Various types of bike infrastructure, including bike paths, bike lanes on roads, and slow-traffic streets, can be part of the network.

Objective B: Cycle parking and storage are ample and secure

Cycling can be an attractive daily travel option only to the extent that bicycles can be securely parked at all destinations, and that bicycles can be secured within private premises at night and for longer periods.

33.2.3Principle 3 | CONNECT

Short and direct pedestrian and cycling routes require a highly connected network of paths and streets around small, permeable blocks. This is primarily important for walking and for public transport station accessibility, which can be easily discouraged by detours. A tight network of paths and streets offering multiple routes to many destinations can also make walking and cycling trips varied and enjoyable.

Short, direct walking and cycling require dense, well-connected networks of paths and streets around short city blocks. Walking in particular can be easily discouraged by detours and is particularly sensitive to network density. A tight network of paths and streets that offers multiple routes to many destinations, frequent street corners, narrower rights of way, and slow vehicular speed make walking and cycling trips varied and enjoyable and invigorate street activity and local commerce. An urban fabric that is more permeable to pedestrians and cyclists than to cars also encourages the use of nonmotorized and transit modes with all the associated benefits.

Objective A: Walking and cycling routes are short, direct, and varied

The simplest proxy for the connectivity of the pedestrian walkway is the size of city blocks, defined as sets of contiguous properties that prevent public pedestrian passage. This block definition might be distinct from the blocks defined by mapped streets, since open pedestrian paths can exist through superblocks and buildings, regardless of public or private property status.

Objective B: Walking and cycling routes are shorter than motor vehicle routes

Although high pedestrian and cycling connectivity is an important feature of TOD, road connectivity enhancing motor vehicle travel is not. An urban fabric that is more permeable to pedestrians and cyclists than to cars prioritizes non-motorized and public transport modes and provides safer, nuisance-free route options.

33.2.4Principle 4 | TRANSIT | Locate development near high-quality public transport

Walkable access to rapid and frequent transit, defined as rail transit or bus rapid transit (BRT), is integral to the TOD concept and a prerequisite for TOD Standard recognition. Rapid transit service connects and integrates pedestrians with the city beyond walkable and cycling ranges and is critical for people to access the largest pool of opportunities and resources. Highly efficient and equitable urban mobility and dense and compact development patterns mutually support and reinforce each other.

Rapid public transit plays an important role not only in providing quick and efficient trips but also in weaving into other frequent and alternative transit options for a complete transit network. These transit options support the entire spectrum of urban transport needs and may come in various modes, including low- and high-capacity vehicles, taxis and motorized rickshaws, bi-articulated buses, and trains.

Objective: High-quality public transport is accessible by foot

For TOD Standard status, the maximum acceptable walking distance to the nearest rapid transit station is defined as 1,000 meters and 500 meters for a frequent local bus service that connects to a rapid transit network within less than 5 kilometers. The transfer station should be designed for short, convenient and all-accessible connections with the rapid transit service.

33.2.5Principle 5 | MIX | Plan for mixed uses, income, and demographics

When there is a balanced mix of complementary uses and activities within a local area (i.e., a mix of residences, workplaces, and local retail commerce), many daily trips can remain short and walkable. Diverse uses peak at different times and keep local streets animated and safe. They encourage walking and cycling activity, support extended hours of transit service, and foster a vibrant and complete human environment where people want to live. People of all ages, genders, income levels, and demographic characteristics can safely interact in public places. A mix of housing options makes it more feasible for workers of all income levels to live near their jobs and helps prevent lower-income residents dependent on lower-cost public transit from being systematically displaced to poorly-served outlying areas. Inbound and outbound commuting trips are more likely to be balanced during peak hours and throughout the day, resulting in more-efficient transit systems and operations. The two performance objectives for the MIX Principle therefore focus on the provision of a balance of complementary activities and land uses and on a diverse mix of resident income levels and demographic attributes.

Objective A: Opportunities and services are within a short walking distance of where people live and work, and the public space is activated over extended hours

To allow many daily trips to be short and walkable, inbound and outbound transit trips to be balanced, and neighborhoods to be active and secure day and night. A mix of uses, services, and incomes helps ensure vibrant and inclusive. If an area has only one type of use, or a heavily dominant use such as office buildings in a business district, the best contribution is to bring new uses and activities that help counterbalance that dominance. Development for locating in, or contributing to, complete neighborhoods, also needs to ensure that access to local sources of fresh food, primary schools, and healthcare facilities or pharmacies. Fresh food is not only a necessity of daily life, but—equally importantly—a reasonably simple-to-assess and reliable litmus test for the wider availability of basic supplies, because it has more rigorous supply chain requirements than nonperishable necessities. Very different processes govern the provision of primary schools and local healthcare services, which are essential local services especially important to poor households. Being able to walk to school, of course, carries health and cost benefits for all. Public parks and playgrounds have multiple benefits—from improved air quality, to reduced heat island effects, to the increased physical and mental health and comfort of residents. Access to parks and playgrounds is particularly important to the urban poor, who have little access to private facilities and few opportunities to break away temporarily from urban life

Objective B: Diverse demographics and income ranges are included among local residents

Social equity is no less important to long-term sustainability than reduced environmental footprints. Mix of incomes is as important to mix of activities and uses to achieve more equitable and sustainable communities and cities. The TOD Standard promotes social equity not only through inclusive access and mobility but also through inclusionary housing and its equitable distribution over the different areas of the city. The Standard also promotes upgrading substandard informal housing in situ, where safe, and generally promotes the protection of residents and communities from involuntary displacement caused by redevelopment. One goal is to avoid creating neighborhoods that reinforce social separation and the concentration of poverty. Another goal is to avoid displacement, which is extremely detrimental to communities. Involuntary displacement leads to the breaking of community ties, the destruction of social capital and networks, and the loss of access to familiar resources and local employment opportunities.

33.2.6Principle 6 | DENSIFY | Optimize density and match transit capacity

A dense model of development is essential to serving future urban development with transit that is sufficiently rapid, frequent, well connected, and reliable at most hours to ensure a satisfactory life free of dependence on cars and motorcycles. Urban density is needed to both accommodate growth within the inherently limited areas that can be served by quality transit and to provide the ridership that supports and justifies the development of high-quality transit infrastructure. From this perspective, urban areas must be designed and equipped not only to accommodate more people and activities per hectare than is usually the case in this age of vehicle-oriented sprawl but also to support highly desirable lifestyles.

Transit-oriented density results in well-populated, lively, active, vibrant, and secure places, where people want to live. It delivers the customer base and the foot traffic that makes local commerce thrive and supports a wide choice of services and amenities. Densification should generally be encouraged to the full extent that it is compatible with daylighting and the circulation of fresh air, access to parks and recreational spaces, the preservation of natural systems, and the protection of historic and cultural resources. As many of the most well-loved neighborhoods in great cities around the world attest, high-density living can be highly attractive. The challenge is to generalize the best aspects of urban density at an affordable cost, mobilize the resources to make it happen with appropriate infrastructure and services, and reform the frequent bias of land use codes and other development policy frameworks toward low densities. And a combination of residential and nonresidential density is needed in support of high-quality transit, local services, and vibrant public spaces.

Objective A: High residential and job densities support high-quality transit, local services, and public space activity

Transit-oriented density results in well-populated streets, ensuring that station areas are lively, active, vibrant, and safe places where people want to live. Density delivers the customer base that supports a wide range of services and amenities and makes local commerce thrive. The limits to densification should result from requirements for access to daylight and circulation of fresh air to living rooms and workplaces; access to parks and open space; preservation of natural systems; and protection of historic and cultural resources. This objective measures both of residential and commercial densities.

33.2.7Principle 7 | COMPACT| Create regions with short transit commutes

The basic organizational principle of TOD is compactness: having all necessary components and features fitted close together, conveniently and space-efficiently. With shorter distances, compact cities require less time and energy to travel from one activity to another, need less extensive and costly infrastructure (though higher standards of planning and design are required), and preserve rural land from development by prioritizing the densification and redevelopment of previously developed land. The COMPACT Principle can be applied on a neighborhood scale, resulting in spatial integration by good walking and cycling connectivity and orientation toward transit stations. On the scale of a city, compact means the city is covered and integrated spatially by public transit systems.

Objective A: The development is in, or next to, an existing urban area

Development should take place on sites within or at the immediate edge of an existing urbanized area, particularly through the efficient use of vacant, previously developed lots, such as brownfields.

Objective B: Traveling through the city is convenient

Development should prioritize areas that offer diverse public transport options and easy commute time to the closest major center of employment and specialized urban services. Developers and project promoters have control over this aspect when making location decisions in the early stage of projects.

33.2.8Principle 8 | SHIFT | Increase mobility by regulating parking and road use

In cities shaped by the above seven principles, the use of personal motor vehicles in day-to-day life becomes unnecessary for most people, and the various detrimental side effects of such vehicles can be drastically reduced. Scarce and valuable urban space resources can be reclaimed from unnecessary roadways and parking and reallocated to more socially and economically productive uses. Conversely, a gradual but proactive reduction of roadways and parking space availability in urban space is needed to lead to a shift in transport mode shares from private motor vehicles to the more sustainable and equitable modes, if matched by sufficient walking, cycling, public transit, and occasional support vehicles.

Objective: The land occupied by motor vehicles is minimized

Off-street and on-street parking space for motor vehicles should be reduced along with the overall street space occupied by traveling motor vehicles. Space should be reallocated to the more economically and socially productive uses of public space and sustainable transportation.