33.1Why TOD: Problems and Solutions

Let’s have a moment of silence for every American stuck in traffic on their way to a health club to ride a stationary bicycle.Representative Earl Blumenauer, United States Congress, 1948-

The forms of land development that best support pedestrians—and therefore public transport riders—are often not in place or complete at the time of a prospective BRT corridor’s planning or construction. These characteristics are in fact rarely found outside historic districts and older transit suburbs of the pre-automobile age.

Urban spaces that have been designed or retrofitted since the advent of the mass-automobile age are generally adverse to pedestrians in two key aspects. First, cars degrade the pedestrian realm through direct nuisances ranging from air pollution and noise pollution to collision hazards and the severance of pedestrian routes by fast-moving car lanes. Second, the basic structure of urban space that fits automobile travel is of a very different scale than that fitting pedestrian travel.

The mass-automobile age started as early as the 1910s in the oldest industrialized nations and began massively impacting cities across the world in the second half of the 20th century. Severe conflicts between the speed and spatial needs of automobiles and those of pedestrians and animals were largely solved by prioritizing motor vehicles at the expenses of pedestrians.

The rise of personal automobiles triggered rather different effects on city streets than the mechanized public transport that had appeared in industrial metropolises of the 19th century. Railroads and streetcars allowed vast metropolitan expansion and a heightened degree of separation between residential and workplace uses, but they still relied on a strong pedestrian realm to provide access to stations at both ends of trips. Mechanized urban public transport expanded the reach of people on foot by providing rapid connections from walking area to walking area. Automobiles allowed door-to-door transport to the privileged segments of population that could afford them and led to the neglect and decline of the public realm of pedestrians and cyclists.

The combined availability of affordable cars and government-supplied roads led to an ever-increasing number of motorists and lengths of their motorized trips. Consequently, driving became the norm in many cities around the world. Congested urban roads were widened and ended up severing communities. The standards and regulations governing the arrangement and design of roads, streets, and new buildings were codified to fit personal cars as a primary mode of transportation. Automobile-centric suburbs, soon dubbed “urban sprawl” for their low density and their disconnection from human scale and aptitude developed, while older, pedestrian-scaled urban areas fell out of favor, often being razed and redeveloped according to so-called “urban renewal” policies.

In a vicious circle, the policies, regulations, and design methods put in place to cope with the traffic, nuisances, and safety issues resulting from motorization triggered more motorization. The generalization of driving-based lifestyles in turn required the construction of ever more roads, interchanges, driveways, garages, and parking facilities, the supply of which was never enough, since traffic increased as soon as new roads or lanes were built. Conceptions of the “good life” now were centered on the ownership and use of cars. Households equipped with multiple cars expected to drive and park them.

Motorization left many behind. Public transport declined along with the pedestrian realm in urban sprawl and urban renewal areas. Low-density settlement patterns did not generate sufficient ridership, resulting in poor service, if any public transport service at all. In dense urban areas, trams and bus speeds went down, as cars jammed the streets, as well as the frequency, connectivity, and quality of service, as riders shifted in numbers to private vehicles. Urban spatial segregation was reinforced, since places characterized by functional and social aspects could be kept physically distant, and yet still be integrated through the use of cars. Meanwhile, the poor who could not afford to maintain an automobile, the young, the old, the women who lacked access to and resources to procure motor vehicles, and all who were unable or unwilling to drive, faced increased travel time and costs while losing access to urban resources.

The negative impacts of car-dependent urban development became obvious as early as the 1950s and 1960s in some countries, with the increase in number of trips and distances traveled, along with a cohort of negative impacts, ranging from road congestion, road casualties, noise and air pollution, and fossil energy consumption to the health ramifications of insufficient physical activity, social segregation and exclusion, unnecessary land consumption, and greenhouse gas emission. Road revolts sprang up in many communities traversed by high-volume road projects.

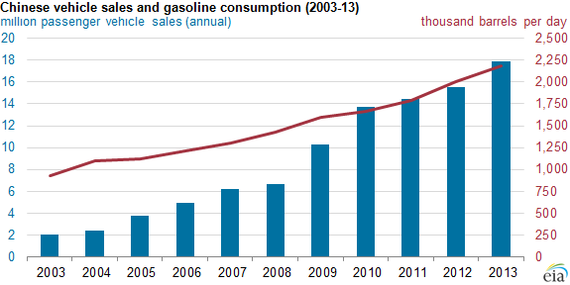

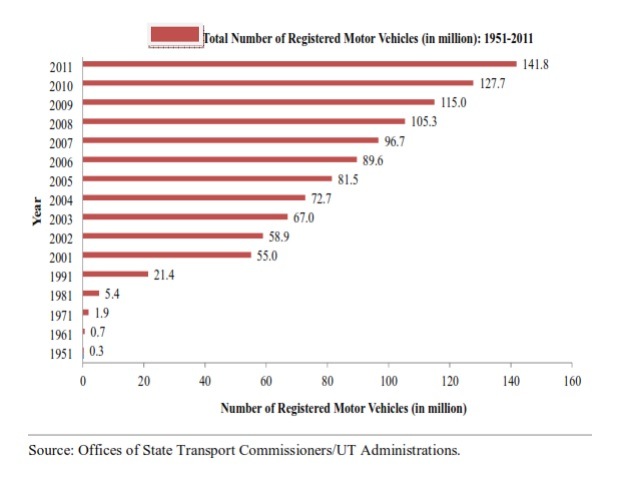

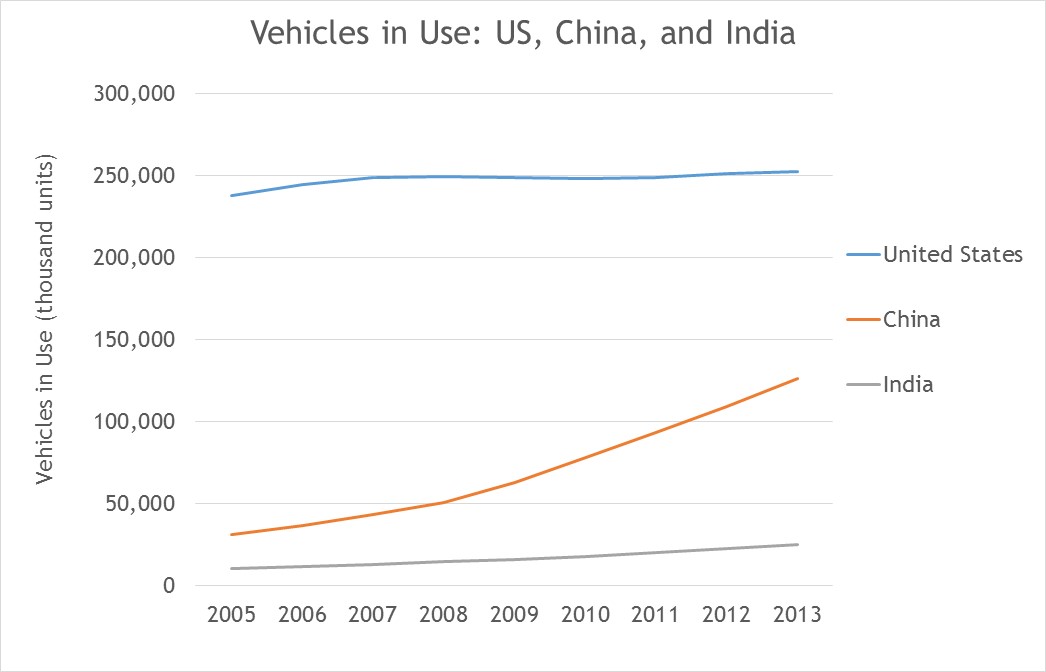

Today, similar processes of car-dependent urbanization are still rolling on in cities around the world, blind to their well-documented, long-term unsustainability. Motorization is massive in many emerging and developing economies.

Many cities still fall into the trap of prioritizing car-oriented infrastructure.

Solutions to car-dependent urban development, insufficient public transport, and degraded pedestrian realms lie in the revamping of public transport, the restoration of urban public realms where people want to be on foot, and the curbing of excessive traffic and parking. The solutions come from bringing people and activities closer together in functional, walking- and cycling-oriented places that can be effectively and efficiently linked by rapid public transport.

These goals have been on the agenda of a small but growing number of cities for at least the past 60 years. The most advanced concepts of modern urban development have evolved considerably in the second half of the 20th century towards more people-friendly and less car-dependent forms. New development, as well as the revitalization of pre-automobile urban fabrics, have been implemented with increasing sophistication and success in cities around the world, from Curitiba, Bogotá, and Singapore to Stockholm, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Portland, Oregon, USA, Vancouver and Toronto, Canada, and Melbourne, Australia, to name a few. In the 2000s, major world cities such as London, Paris, and New York overturned their policies on transport, urban development, and the pedestrian and cycling realm quite spectacularly. From China to Argentina, cities around the world are turning to a new era of walking-, cycling-, and transit-oriented urban development.