32.4Case Studies

Yesterday I parked my car in a tow-away zone... when I came back the entire area was missing.Steven Wright, comedian and actor, 1955–

32.4.1BRT and Parking Management in Ottawa, Canada

The Ottawa Transitway is perhaps the most successful busway in North America. In a city of 800,000 people, the daily ridership on the Transitway is 240,000. Like the five true BRTs in the United States, the Ottawa Transitway’s four corridors score as bronze on The BRT Standard. The success of the Ottawa Transitway can be attributed to three factors:

- Federal government offices are concentrated in the city center;

- Free parking was discontinued for civil servants in 1975;

- Zoning bylaws have decreased required parking spaces.

Parking reductions along with density increases are viewed as incentives for developing near the public transport stations, subject to individual approval. As a result, development did occur around the BRT stations. At the same time, park-and-ride facilities were permitted only at the termini of the Transitway.

When the Transitway opened in 1983, the federal government, Ottawa’s largest employer, began eliminating free parking for its employees and reduced parking availability downtown by 15 percent. Additionally, retail centers receive a reduction of twenty-five parking spaces for every bus stop provided either on-site or through a physically integrated Transitway station.

Today, the City of Ottawa’s zoning bylaw includes progressive parking policies such as:

- Reduced parking minimums in the central area and downtown;

- Parking maximums within 600 meters of public transport stations (BRT or LRT) and reduced maximums in the central area and downtown;

- A shared parking policy in which users that generate parking demand at different times of the day are able to share spots that count toward their minimum;

- The ability for developers to pay cash that will allow them to reduce their parking requirements;

- Priority to short-term parking in developments so that commuters are more likely to use public transport.

The city also employs a parking pricing strategy that discourages long-term parking.

32.4.2Congestion Pricing in London

The introduction of congestion charging in London helped broaden the appeal of congestion charging to transport planners worldwide. Over the past decades, London’s traffic congestion had worsened to the point that average traffic speeds were similar to speeds of the horse carts utilized in London during the nineteenth century. In response, London’s Mayor Ken Livingstone decided to implement a congestion charging scheme in the center core of the city.

As of 2012, a US$16 fee is imposed upon vehicles each time they enter the central zone from 7:00AM to 6:00PM, Monday through Friday. Motorists can pay through a variety of mechanisms including the internet, telephone, mobile text messages, self-service machines, post, and retail outlets (Figure 32.12). Those who take advantage of Autopay only pay US$14.25 each time that they are billed to a debit or credit card. Motorists have until midnight on the day of entry to pay the charge. Payments can still be made the next day, although the price increases to US$19. Subsequently, a US$190 fine is applied to motorists who fail to pay by midnight of the following charging day. If paid within fourteen days, the penalty is reduced to US$95. If no payment is made after twenty-eight days, the fine increases.

The London system differs from the Singapore system in several ways. First, the London system does not require an in-vehicle electronic unit, and requires no system of cash cards. It is an enforcement-only system. London does not utilize gantries but instead relies upon camera technology to identify the license plates of all vehicles passing the point and sends this information to a central computer (Figure 32.13). At the end of each day, the list of vehicles identified entering the zone is compared to the list of vehicles that have made payments to the scheme operators. Any unpaid owners are referred for enforcement actions.

London adopted a camera-based system rather than an electronic-gantry system for several reasons. First, the elimination of the in-vehicle electronic system and cash card would hopefully reduce administration costs. Second, London also had aesthetic concerns over the large overhead gantries employed in Singapore. Third, officials were concerned over the limitations of GPS-based systems to operate without interference in narrow urban roads lined by tall buildings.

London’s system has some disadvantages. Unlike the Singapore system, London’s system has to charge a flat fee for a carefully defined area. To win political support, residents with motor vehicles inside the charging zone were given a 90 percent discount. This exemption has made expanding the zone difficult, as expanding the zone would also increase the number of people eligible for the discount. After the implementation of a western extension in 2007, it was dismantled by the new administration in 2011. Congestion is not uniform around a zone, particularly a larger zone. For a larger zone, it may be that there is minimal congestion on access roads serving lower-income areas and higher congestion on access roads serving higher-income populations. A point-specific charging system like Singapore has much greater potential to optimize charges to specific points of congestion.

The license plate detection is not required to ensure payment, but rather it is only required to enforce nonpayment. For this reason, the system does not have to be 100 percent accurate; the system is only accurate enough to induce people to pay the fee voluntarily. The London system also has some trouble charging motorcycles, which are therefore exempt. The cameras incurred a failure rate of between 20 and 30 percent in reading motorcycle license plates due to the smaller size of the plates and the fact that motorcycles do not always operate in the center of the lane. Some license plates can be difficult to read due to bright glare or obstructions from trucks. In London motorcycles are exempted to ensure a high level of consumer confidence in the system, but in other cities with a large number of motorcycles they would need to be included.

In addition to exempting motorcycles, the London congestion charge is also not applied to taxis, public transport, police and military vehicles, physically disabled persons, certain alternative-fuel vehicles, certain health-care workers, and tow trucks. As of 2011, vehicles that emit 100 grams per kilometer or less of CO2 and meet the Euro 5 standard for air quality will only need to pay US$15.83 a year per vehicle to receive the exemption. This measure is in line with London’s vision to improve air quality and tackle climate change. The exempted vehicles represent 23 percent (twenty-five thousand vehicles) of the total traffic in the zone.

London’s congestion charge has produced some impressive results. Congestion levels have been reduced by 30 percent after the first year, and the total number of vehicles entering the zone has dropped by 18 percent. Average speeds increased from 13 kilometers per hour to 18 kilometers per hour. Perhaps the most unexpected benefit was the impact on the London bus system. With less congestion, bus journey speeds increased by 7 percent, prompting a dramatic 37 percent increase in bus patronage. The revenues from London’s program are applied to supporting bus-priority infrastructure and bike-lane projects.

32.4.3Congestion Charging in Stockholm

Stockholm joined London and Singapore in January 2006 as a large global city employing a congestion charge. Stockholm borrowed concepts from its two predecessors while also invoking several more recent technological innovations. The Stockholm charge was implemented after a seven-month trial period, with a majority of support from a public vote on whether to keep it.

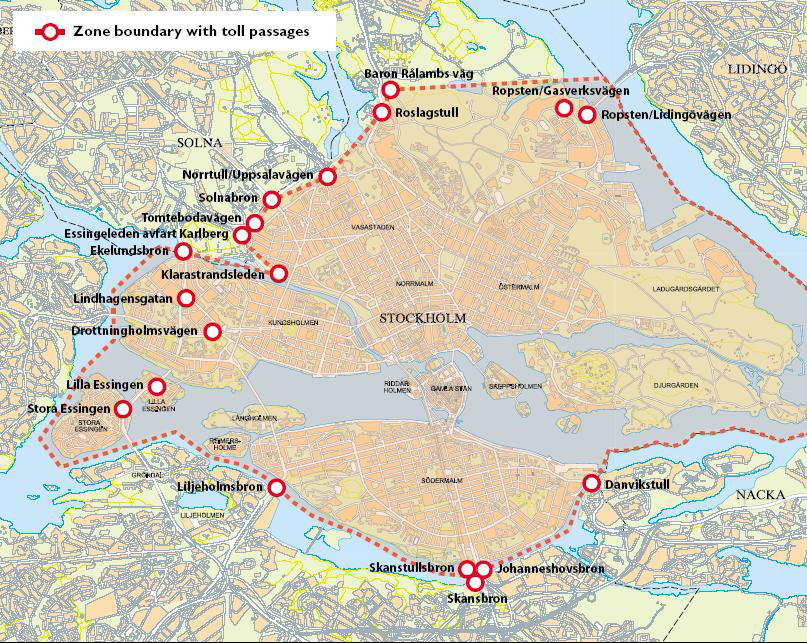

Stockholm’s charge zone includes the entire central area of the city, with a total of nineteen different gantry points permitting entry into the zone (Figure 32.14). Like Singapore, Stockholm has a fortuitous location, with bodies of water restricting the number of actual access points to the city center. Such naturally restricted entry eases the technical tasks of controlling a large number of entry points.

The amount of the Stockholm charge depends on both the number of times a vehicle enters the central zone as well as the time of day (Table 32.2). For vehicles entering and exiting the charge zone multiple times per day, the maximum amount to be paid is US$9. Like London and Singapore, several types of exemptions are permitted, including emergency vehicles, public-transport vehicles and school buses, taxis, vehicles with disability permits, environmentally-friendly vehicles (e.g., electric, ethanol, and biogas), and motorcycles. The capital cost for the six-month trial period of the charge was SEK 3.8 billion (or US$572 million in 2013 equivalent value) (Pollard, 2006).

Table 32.2Fee schedule for the Stockholm congestion charge

| Time of crossing zone boundary | Cost (SEK) | Cost (US$) |

|---|---|---|

| 06:30 – 07:00 | 10 | US$1.50 |

| 07:00 – 07:30 | 15 | US$2.30 |

| 07:30 – 08:00 | 20 | US$3.00 |

| 08:30 – 09:00 | 15 | US$2.30 |

| 09:00 – 15:30 | 10 | US$1.50 |

| 15:30 – 16:00 | 15 | US$2.30 |

| 16:00 – 17:30 | 20 | US$3.00 |

| 17:30 – 18:00 | 15 | US$2.30 |

| 18:00 – 18:30 | 10 | US$1.50 |

| 18:30 – 06:30 | 0 | US$0 |

Stockholm uses two different types of vehicle-detection technologies, which are similar to both the technologies used in London and Singapore. For regular travelers to the central area, motorists can obtain an electronic tag that automatically reads the vehicle’s entry into the area. With this electronic tag, the appropriate fee is automatically deducted from the person’s bank account. Approximately 60 percent of the people entering the zone utilize the electronic tag.

Alternatively, for vehicles not employing the electronic tag, a camera technology similar to that of London is utilized. The camera detects the plate number on the vehicle, and the motorist has five days to pay the charge by post or at a shop. If the charge is not paid within five days, then a fine of US$11 is assessed. After four weeks, the unpaid charge results in a fine of US$80 (Webster, 2006).

In the first month of operation, Stockholm’s congestion charge reduced congestion levels by 25 percent, which is equivalent to reducing private vehicle travel by approximately 100,000 cars each day. While London’s charge only applies once per day, in Stockholm drivers must pay each time they enter the congestion zone. The congestion charge has both influenced the time that people travel as well as their mode of choice. Approximately 2,000 drivers now travel to work earlier in order to enter the zone prior to the 06:30 start of the charge. Another 40,000 private motorists have now switched to public transport (Public CIO, 2006).

Perhaps the most instructive lesson from Stockholm has been the manner of implementation. The congestion charge was applied as a six-month trial that ended in July 2006. In September 2006, the public voted on whether to continue with the charge. At the outset of the congestion charge experiment, approximately two-thirds (67 percent) of the public was opposed to it. On September 17, 2006, 52 percent of the public approved the referendum to make the congestion charge permanent.

The referendum approach can thus be an effective mechanism to gain public support, permitting an initial trial. Otherwise, protests at the outset may prevent a project from happening at all. This approach, though, is not without its risks. As people experience the benefits of reduced congestion, support for the measure may dramatically increase, as was the case in Stockholm. Nevertheless, any city employing a referendum approach to project approval and project continuance must be prepared for a negative vote. However, giving people a democratic voice in applying TDM measures can be an approach that warrants serious consideration.

32.4.4Congestion Charging in Tehran

The success of the London, Singapore, and Stockholm pricing plans has attracted interest for similar projects in developing cities. The high-tech nature of congestion charging can increase its attractiveness to officials seeking to increase modern technologies in their cities.

Tehran, Iran, is the most successful city to implement congestion pricing since London. The system first began operation at the end of April 2010, using Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) technology that takes photos of license plate numbers as they cross the cordon. Drivers must purchase a permit prior to entry in the charging zone. The plate numbers are cross-checked with registered vehicles at a control center. Daily permits cost US$11.60, weeklong permits are US$70, and annual permits cost US$174. Payment can be done online or by phone. Drivers who do not pay in advance must pay a maximum penalty of US$6,500. Disabled drivers can get a discount for the permit. Meanwhile, government and commercial vehicles all must pay, with a bigger charge for vehicles registered to companies. Tehran’s system includes 104 entrance points. Now, enforcement personnel circulate in the charging area to stop vehicles travelling without a permit. Initially, the system was enforced with police stationed at select intersections at the perimeter of the charging zone. Similar to Singapore, the system evolved to a more technologically driven solution.

The area charge complemented the BRT that started operation in 2008. By 2011, the system already carried 1.8 million customers per day. During this time, it was reported that pollution decreased by 45 percent and travel times had decreased by 55 percent, largely due to the removal of private cars from the road. According to a Global Mass Transit report, nearly 35 percent of riders on the BRT system had never used public transport before it was implemented.

32.4.5Roadway Restrictions in Seoul

Perhaps one of the most spectacular examples of this concept in practice is the Cheonggyecheon corridor project in Seoul. The Cheonggyecheon stream was historically a defining part of Seoul’s environment, and in fact was the reason why Seoul was selected as the capital of the Joseon Dynasty in 1394. In the face of modernization, the waterway was covered in 1961 to provide better access for private vehicles. By 1968, an elevated expressway provided another layer of concrete—erasing the memory of the waterway.

Upon his election in 2002, Seoul Mayor Myung Bak Lee decided it was time to bring back the Cheonggyecheon stream. The Cheonggyecheon project has meant the restoration of 5.8 kilometers of waterway and historical pedestrian bridges, the creation of extensive green space, and the promotion of public art installations (Figures 32.15 and 32.16). Based upon a study by the Seoul Development Institute (2003), now known as the Seoul Institute, the Cheonggyecheon restoration project was predicted to produce economic benefits of between US$8 billion to US$23 billion, and create 113,000 new jobs. More than forty million visitors experienced the Cheonggyecheon stream during the first year after restoration.

Further, despite the elevated expressway being the principal access way for cars into the city center, there were no significant congestion impacts. In part, the new Seoul BRT system helped defray some of the traffic impacts (Figure 32.17).

Softer “pull” tactics on this front include the weekly no driving day program in Seoul. People can get free parking, reduced-cost car washing, and reduced taxes and congestion charges if they use alternative transport at least one day every week. Participants receive a sticker for the rear window of their car, which is monitored using RFID technology to assess compliance. According to the city, the program has reduced traffic volumes by 3.7 percent since 2003, with a CO2 reduction of 10 percent and fuel savings amounting to USD$50 million.

32.4.6Travel Blending in Santiago, Chile

Several cities in Australia and Europe have developed a new technique for achieving dramatic changes in mode shares at very low costs. The technique, known as “travel blending,” is a form of social marketing. The idea is to simply give people more information on their commuting options through a completely personalized process, and then facilitating changes in travel behavior. This can help decrease the number of private motor vehicles on the road, as drivers decide to shift to BRT. More information on this technique is provided in Chapter 11: Marketing.