30.1Introduction

Some do not walk at all; others walk in the highways; a few walk across lots.Henry David Thoreau, author and naturalist, 1817–1862

Most customers benefit from inclusive features on and around BRT systems. For example, everyone benefits from good sidewalks leading to BRT stations, a narrow platform-to-vehicle gap, nonskid floors, plentiful handholds on BRT vehicles, audio and text signage in stations and on vehicles, and drivers trained to avoid sudden starts and stops. However, for customers with special needs, inclusive design often makes the difference between being able to use the system or not. Such customers include:

- Customers with permanent or temporary physical disabilities, including those who use canes, crutches, or wheelchairs, and those with hidden disabilities such as arthritis or a heart condition. Most frail elderly persons will fit into this category;

- Customers with sensory disabilities, such as blind persons, those with reduced vision, and persons who are deaf or hard-of-hearing;

- Customers with temporary or permanent cognitive challenges, such as first-time BRT users, people who do not speak the language, the illiterate, and tourists;

- Children and young customers, who may need more orientation than other customers, or benefit from design features for short persons;

- Customers with children, or pregnant women;

- Customers travelling with packages and luggage.

The number of people who benefit from universal design is growing. According to United Nations data, existing BRT systems must incorporate an average of over 40 percent more older persons into their service areas during the next twenty years.

30.1.1Not Just Wheelchairs

Because wheelchair users are especially identifiable, they have become surrogates for other categories of beneficiaries of universal design. This contributes to the general practice of saying a vehicle “is accessible” or “is not accessible” solely based on the ability of customers using wheelchairs to get on the vehicle. Yet, for every wheelchair user, there are up to four persons using canes, crutches, or other mobility aids, and the percentage of persons with disabilities with sensory and cognitive disabilities is greater than the percentage with mobility impairments.

30.1.2Where are the Special Needs Customers?

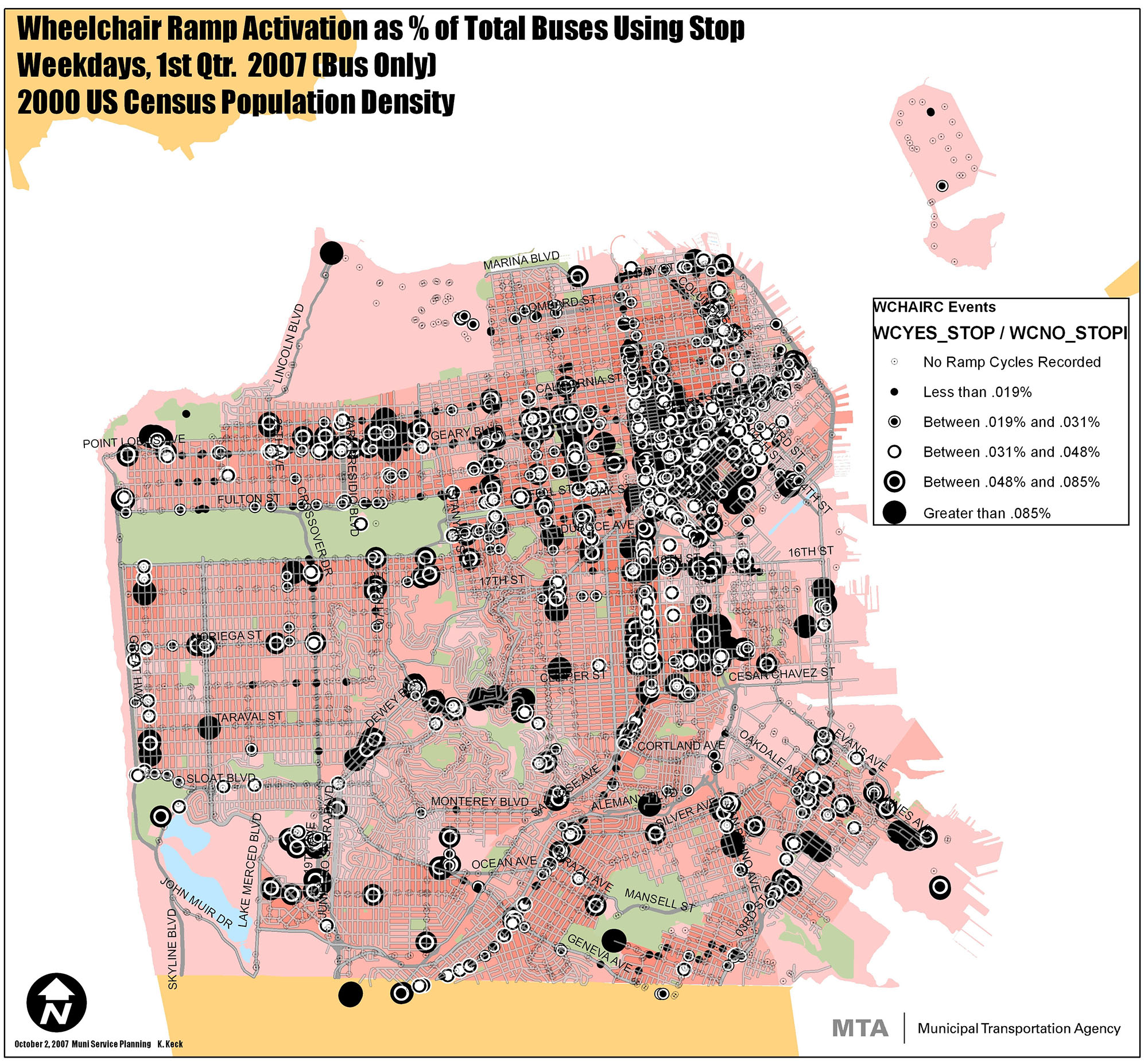

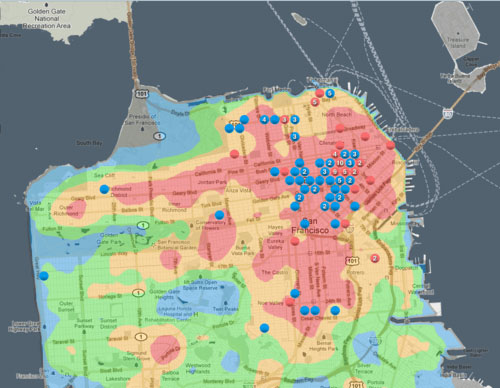

Trips by the disabled tend to parallel travel patterns of all other customers. The assumption that they are concentrated in select areas is seldom correct in regions with accessible public transport systems and a culture of independent living. The maps below illustrate the experience of San Francisco, California, USA.

30.1.3Can Public Transport Accommodate the Disabled?

Public transport systems, including BRT, can and do play a role in accommodating the disabled.

- Curitiba provides 21,000 daily trips for registered disabled persons (slightly under 1 percent of all trips). Of this number, about 1,000 individual wheelchair users ride the system daily, implying in excess of 500,000 one-way trips per year, forming part of 8 million annual trips by all registered disabled persons and their attendants. This number does not include unregistered users.

- San Francisco, California, provides 180,000 to 200,000 trips by wheelchair users per year system-wide, or approximately 200 trips per year per vehicle in peak hour service.

Crafting a BRT system accessible to all, from those with hidden disabilities to those in wheelchairs, benefits everyone and remains the goal of a just and equitable society.

30.1.4Islands of Accessibility

A full-featured BRT corridor may begin its life as an island of accessibility in a sea of inaccessibility. Streets with no sidewalks, sidewalks with no ramps, sidewalks in disrepair, noncontiguous sidewalks, vehicles parked in the road and on the sidewalk, sidewalks jammed with vendors, shops, and garbage, and drivers who do not yield to pedestrians all limit access to public transport. Accessible BRT counters this. It can stimulate a growing network of accessible streets and sidewalks reaching far beyond the actual BRT.