30.3Station Access

Be an opener of doors.Ralph Waldo Emerson, essayist and poet, 1803-1882

Chapter 29: Pedestrian Integration covers pedestrian access to stations and terminals. This chapter highlights specific accessibility issues.

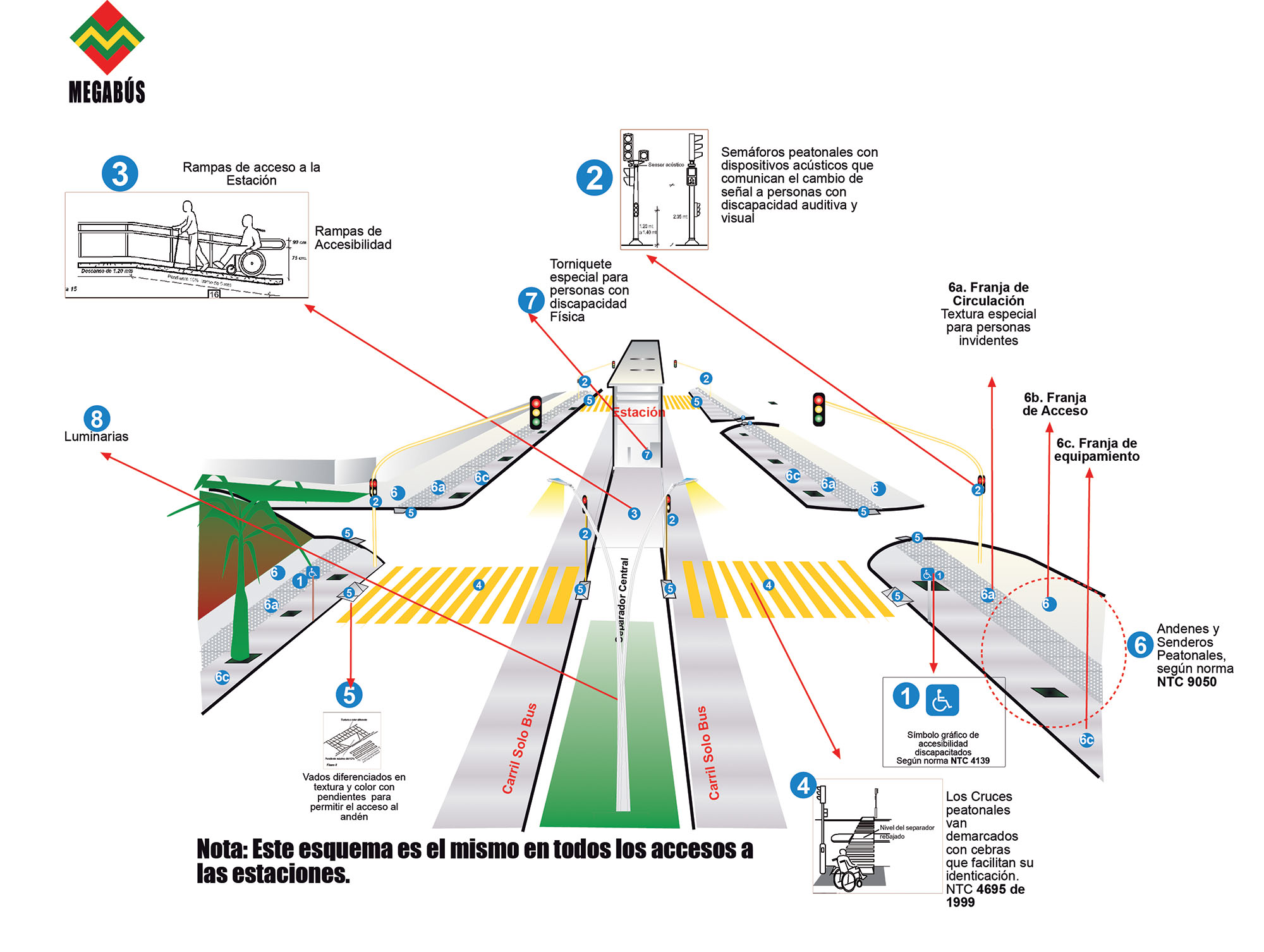

The image below summarizes some of the main features detailed in this and the following section.

- Universal accessibility symbol;

- Traffic lights with acoustic signals;

- Access ramps;

- Well-marked pedestrian crossings;

- Curb ramps with color and texture differentiation;

- Accessible pedestrian walkways;

- Wide fare gates.

30.3.1Walkways

Walkways refer to any facility used by pedestrians, including sidewalks, pavements, shared streets, footpaths, and paths. As a general rule, accessible and well-lit walkways should exist along the main approaches to all BRT stations. They should extend for at least 400 meters in all directions. Ideally, they should exist along the entire length of any BRT trunk line. The following are critical accessibility elements and dimensions for walkways:

- Straight and unobstructed;

- Smooth, even, well-paved, nonskid surfaces;

- Contrasting color for street furniture and other obstacles;

- Minimum passing width for a wheelchair at an obstruction—0.9 meters;

- Minimum overhead clearance (at signs)—2.0 meters;

- Maximum cross-slope (for drainage)—2 percent;

- No gratings or other items that would catch the small front wheels of wheelchairs;

- Maximum opening or gap in a grating—13 millimeters.

30.3.2Tactile Guideways

Tactile guideways are characterized by a series of raised parallel bars pointing in the direction of travel. The bars are typically molded into a 300-millimeter-square tile, installed one or two tiles wide. They benefit blind persons and those with reduced vision and help others to find their way:

- Across large unmarked areas;

- Along complex paths to a specific destination (information booth, BRT station);

- On walkways without a well-defined boundary with the road.

Guideways should be used in a consistent manner within a country and should be in a color contrasting with their surroundings. Research has shown that grooved concrete is not detectable underfoot. Therefore, texture differences should be detectable under foot and by a long cane.

In BRT environments, a tactile guideway is useful to mark a travel path from a sidewalk to a pedestrian crossing to a BRT station. It can continue on the other side of the crossing, turning up the ramp into the station and proceeding to the ticket vending and information booth. The guideway can then proceed down the center line of the station, with guideways branching off at right angles to station doors.

30.3.3Tactile Warnings

Tactile warnings, also called attention patterns and detectable warning strips, are characterized by a series of raised truncated domes, typically molded into a 300-millimeter-square tile. They mark edge or stop locations, such as platform edges or curb ramps. They are typically two tiles wide to assure that pedestrians do not step over them. They are of a contrasting color with the surrounding surface. In some countries, tactile warnings are placed immediately adjacent to the edge or curb, while in other countries they are placed 600 to 1,000 millimeters away. Tiles are recommended as they can be detected by canes as well as underfoot. Maintenance is key so that broken tiles do not become trip hazards (Bentzen and Barlow 2011).

30.3.4Curb Ramps

Curb ramps (also known as pedestrian ramps, wheelchair ramps, and curb cuts) are ramps that allow a person in a wheelchair to roll up or down at a curb, instead of stepping. They benefit people with walkers, strollers, bicycles, carts, and anyone else who has trouble with steps. The slope of a curb ramp is critical, lest a person in a wheelchair fall backward. Also critical is placing a curb ramp at the opposite side of the street.

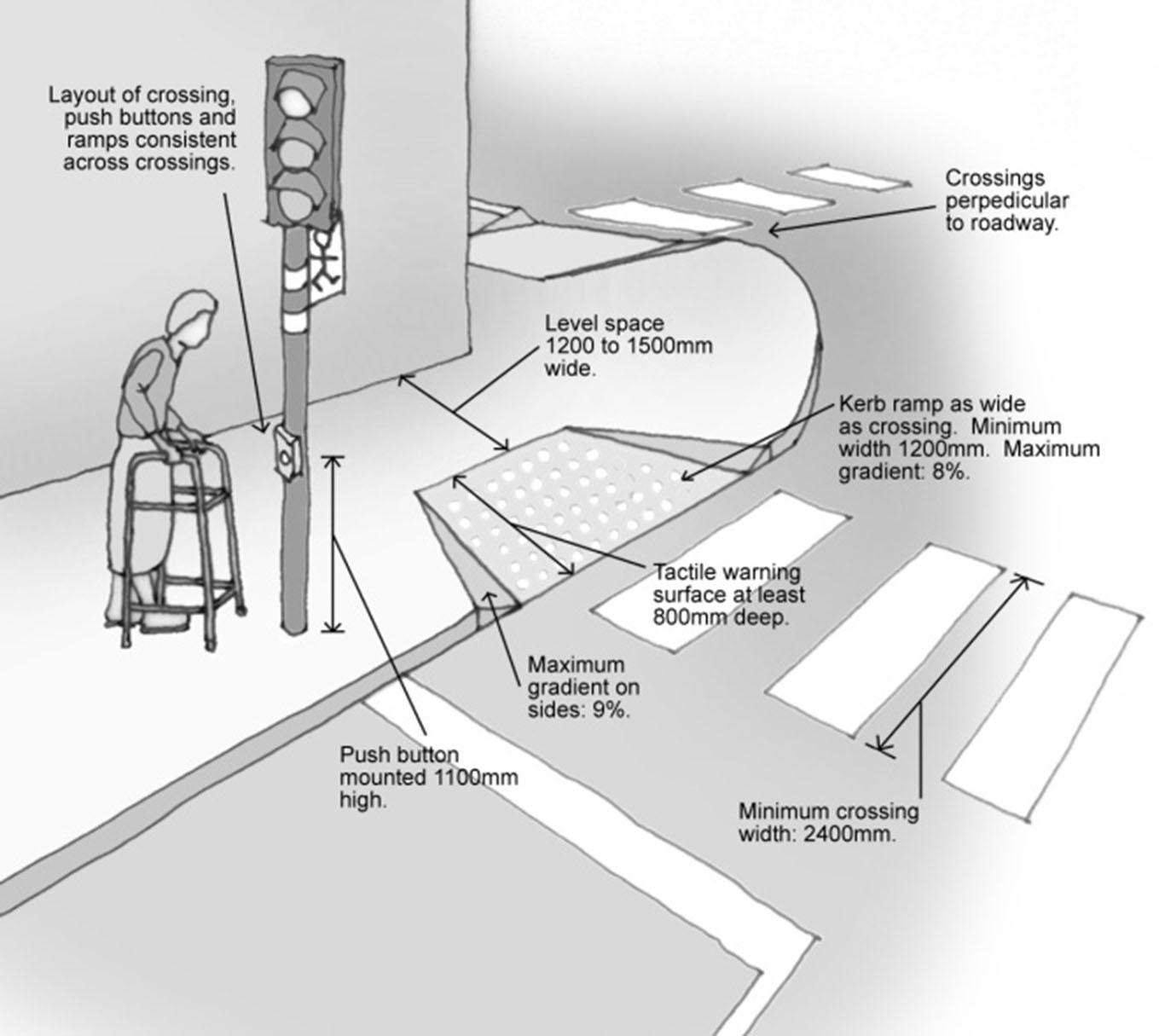

General curb ramp requirements, based on TRL guidelines:

- Placement: within crosswalk markings;

- Orientation: perpendicular to curb (creates a flush public transportation);

- Width: ideally equal to crosswalk width, minimum 1.2 meters;

- Slope: maximum 1:12 (8 percent);

- Side flange slope: 1:10 (9 percent);

- Level landing and turning area: 1.5-meter square at top and bottom of ramp;

- Tactile warning strip at base of the ramp.

Curb ramps should be required in all new construction, and there should be a program to retrofit existing streets. As a priority, curb ramps should be installed on routes between BRT stations and important trip generators.

30.3.5Raised Crossings

An alternative to curb ramps is a raised crosswalk (raised crossing, raised intersection, continuous sidewalk). Here the street is raised to sidewalk level, and pedestrians cross without having to step down to street level. It is recommended for all streets with speeds of 50 kilometers per hour or less and may be used elsewhere.

30.3.6Traffic Signals

Where traffic signals are employed, they must be timed so that slower pedestrians have sufficient time to cross the street (0.75 meters per second). Countdown, tactile, and audible indicators are preferred.

30.3.7Pedestrian Bridges and Tunnels

As discussed in Chapter 29: Pedestrian Access, at-grade crossings are preferred to access BRT stations. Should a pedestrian bridge or tunnel be considered, a tunnel with ramps is preferred. The second choice would be a bridge with ramps. Elevators are a last choice for reasons other than accessibility.

Tunnels are preferred because they require less vertical clearance (than a bridge over a roadway), thus the ramp slope and/or distance is less. While bridges with ramps may be technically “accessible” to a wheelchair user, the sheer length of ramps to pedestrian bridges is so daunting that most wheelchair users are unlikely to use the ramp without the help of a friend to push the chair. Customers with less visible disabilities, such as arthritis or a heart condition, may also find long ramps difficult to access. Elevator procurement is costly, and elevator maintenance can become an issue for the operator. For this reason, Bogotá’s TransMilenio will avoid elevators in the future.

30.3.8“Special” Crossings

Persons with disabilities should cross the street and access BRT stations along with everyone else. “Special” crossing and access points are to be discouraged. This practice relies on the presence of security or traffic personnel, which may or may not be available, and it has been viewed as preventing access by persons with mobility impairments in Latin American and Asian countries.

30.3.9Ramps to BRT Stations

Ramps are the preferred method of access to BRT stations, as opposed to elevators or stairs. Station assistants may be assigned to assist wheelchair users and others who need help up the ramp.

General ramp criteria (TRL 2004, pp. 145–146):

- Width: equal to station width;

- Slope—1:20 (5 percent), maximum 1:12 (8 percent);

- Run (length)—maximum 9 meters with no resting area;

- Rise (height)—maximum 0.75 meters with no resting area;

- Level resting area dimensions—equal to width of ramp by 1.5 meters;

- Handrails on both sides;

- Level landing and turning area—1.5 meters square at top and bottom of ramp.

The norms in some countries specify a level resting area after a maximum run of 6 meters (e.g., Argentina’s Ley Nacional 24314), others specify 9 meters, and others specify other lengths. Section 4.8 of the United States’ ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) states, “The shortest possible grade for a ramp shall be used. The maximum angle for a ramp in new construction should be 1:12. The maximum rise should be 30 inches (760 mm)” before a horizontal resting area.