2.3Planning and Development

Plan for what is difficult while it is easy, do what is great while it is small. The difficult things in this world must be done while they are easy, the greatest things in the world must be done while they are still small. For this reason sages never do what is great, and this is why they achieve greatness.Sun Tzu, Military strategist, 544–496 BC

The window of opportunity for implementing new public transport is sometimes quite limited. The terms in office of key political champions are generally only three to five years. If implementation is not initiated during that period, the following administration may well decide not to continue the project. In some instances the project may be cancelled just because the new administration does not want to implement someone else’s idea, regardless of the merits of the particular project. A longer planning and development period also means that a host of other special interest groups will have more opportunity to delay or obstruct the process. Ideally, a public transport project can be planned and implemented within a single political term. This short time span may provide an additional incentive to a potential project champion, as it provides the opportunity to finish the project in time to reap the political rewards; BRT’s recent popularity in part is this condensed project timetable.

2.3.1Implementation Speed

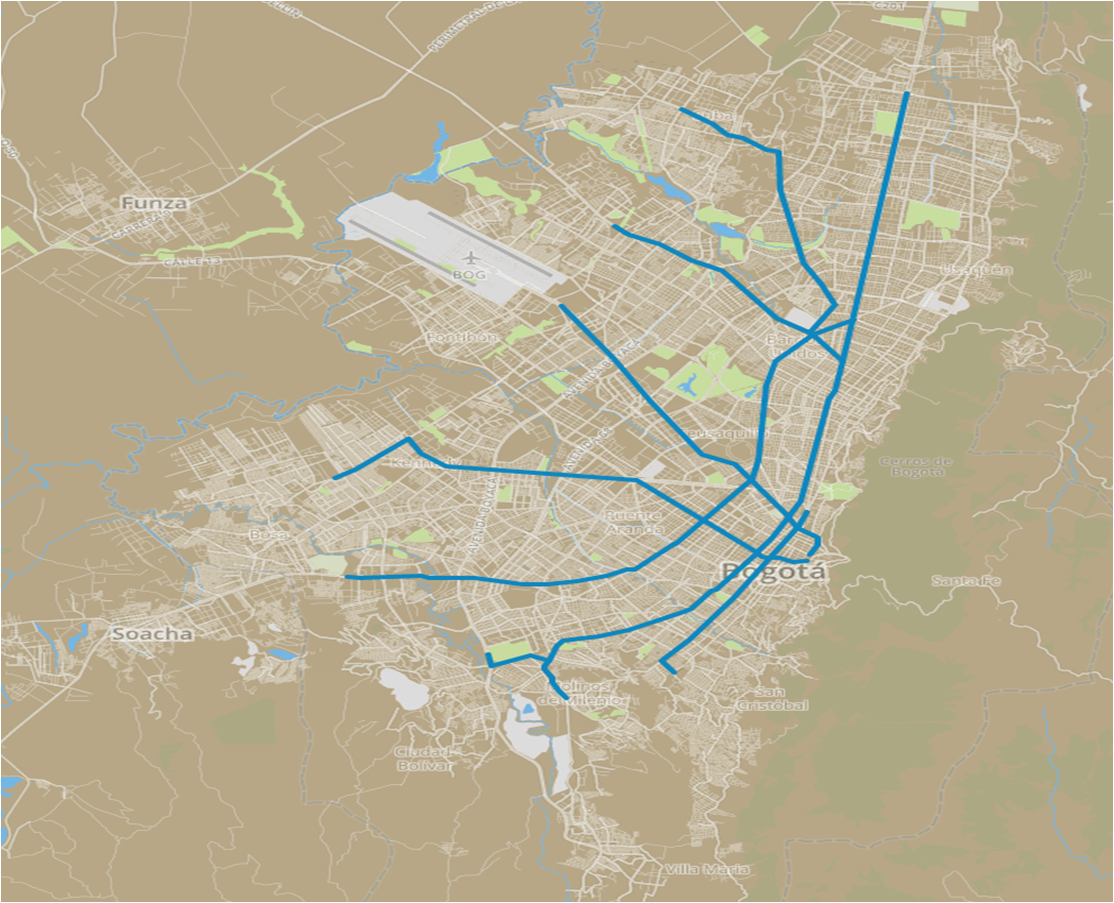

A BRT can be designed and implemented within an extremely short time frame. A few very good projects around the world, like the Guangzhou BRT and Bogotá’s TransMilenio, went from a firm political commitment to implementation within eighteen months. A more reasonable time horizon is three to four years, as was the case for the Pittsburgh South Busway BRT and the Los Angeles Orange Line BRT. In many cities around the world, a major selling point for BRT is that mayors or governors are able to get the projects built and operational within a single term of office, as happened in Bogotá during the 1998–2001 term of Mayor Enrique Peñalosa.

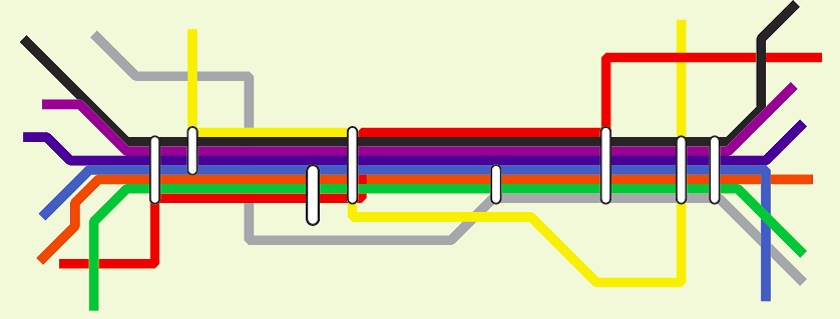

LRT projects tend to have much longer time horizons. This means that one politician might make a promise to build LRT, only to have it realized by yet another politician years into the future. It also means that the public transport and land use benefits can be felt much more quickly with BRT than with rail-based modes. Planning a more-complex rail project can typically consume three to five years of time (Figure 2.7), and construction can also take an additional three to five years to compete, as the examples of the Bangkok SkyTrain and the Delhi Metro show.

Obtaining the project financing can be another significant time delay. Most rail projects have much higher capital costs, and thus require additional time to identify funding sources and negotiate the terms with other levels of government and financial institutions. BRT projects, due to their lower capital costs, can more often be financed largely by the municipality, with less need to involve other levels of government or protracted negotiations with financial institutions.

2.3.2Scalability

Transit projects have to be built in minimum operational segments. BRT provides much greater flexibility in terms of phasing construction to accommodate the project budget size. A city can build high-quality BRT along just a segment of an existing bus route where the BRT infrastructure is most needed, then extend this BRT infrastructure farther along the corridor as money becomes available and the need for these measures increases. In other words, a BRT can run bus services in mixed traffic, and only use BRT infrastructure for the short segment where the bus route faces the worst traffic congestion or the greatest boarding and alighting delays, usually in a downtown area.

With LRT or HRT, operating a very short segment first rarely makes economic sense. A very short LRT or HRT can only operate where there are tracks and stations. Hence, short operational links in an LRT or HRT will force most passengers to make transfers both to reach the LRT/HRT and to continue from the end of the new LRT/HRT line to their destination.

Public transport systems with higher construction and operating costs need high passenger numbers to financially sustain them. For the same reasons, such systems may necessitate a larger network in order to operate effectively. Therefore, the faster you can build a larger network, the sooner the system will be able to recover a reasonable share of its operating costs. With its shorter implementation time and lower capital costs, BRT can be built into a network more quickly.

There are also economies of scale in production of transit infrastructure. A city that has a large rail transit network can generally better afford the sophisticated equipment needed to build and maintain such systems than a city with only one LRT or HRT line. For BRT, however, since construction techniques for BRT are not so different from normal roadway construction, the required economies of scale are far less acute than those for other types of systems. BRT has been developed in cities with populations of 200,000 to megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants. Even relatively small system additions can be economically accommodated by BRT. Thus, BRT allows cities to have a public transport system that grows and evolves in close concert with the demographic and urban form changes that occur naturally in a city.

2.3.3System Flexibility

Modern modelling and planning practices have greatly aided the objective of matching public transport design to passenger needs. Unfortunately, even the best-crafted plans cannot account for all eventualities. Customer preferences can be difficult to know with absolute certainty. The nature of a city’s urban form and demographics can change as social and economic conditions change. Thus, it is always preferable to have a public transport system that can grow and change with a city.

During the start-up phase of a new system, passenger reactions and preferences are usually different to some degree than the original predictions indicated from modelling exercises. Demand in one area may exceed or fall short of expectations and require service adjustments. Alternatively, customer demand for express or limited-stop services may be quite different from early projections, or emerge much later in the life of the system. New routes may be added to account for development in a satellite area.

The relative flexibility of BRT means that such changes can often be accommodated at a modest investment in terms of time and money. Changes to the Bogotá TransMilenio system were handled smoothly within the first weeks of opening. By contrast, routing and service changes to rail-based systems are much more complicated and expensive, as new tracks, crossovers, and signals must be installed. Thus, rail-based systems require a good deal more certainty in terms of the required demand and service preferences.

In addition to being adaptable to route and demand changes, BRT offers the added flexibility of being able to provide more direct door-to-door service. A BRT vehicle can operate in mixed traffic on normal streets and then enter dedicated BRT infrastructure without forcing passengers to transfer to another vehicle. LRT, by contrast, can only operate where there are rail tracks, and passengers coming from locations not served by the tracks must make longer walks or bicycle rides, transfer to and from buses, or utilize space-consuming park-and-ride lots in order to use the system. A transfer can pose significant delays and inconvenience to passengers and is sometimes enough to turn people away from mass transit.

It is also easier to introduce express and limited-stop services into BRT systems, since an express bus simply needs a passing lane at stations or the ability to pass in a regular traffic lane at stations, whereas rail-based transit systems essentially require double-tracking throughout for express services. At an average cost of US$41 million per mile, double-tracking rail is generally prohibitively expensive. Often, a conventional bus route ends up serving a limited- or express-stop service parallel to light-rail but without the benefits of the LRT infrastructure. Express services are one of the most important ways to increase bus speeds. It was the introduction of a large number of express services to Bogotá’s TransMilenio that resulted in that system’s high average speeds and capacities.

2.3.4Phasing

Because buses can operate both in and out of the BRT corridor, it is much easier to implement and expand BRT systems in phases, with less disruption to existing transit routes. Implementation of LRT, on the other hand, requires extensive service changes along a corridor. Existing bus routes must either stop at the LRT corridor, requiring an additional transfer, or operate parallel to the LRT without benefiting from the new infrastructure. Each expansion of the LRT infrastructure requires similar service changes. As a result, LRT systems are typically only implemented in large contiguous segments, in order to avoid multiple disruptive service changes. This reduced ability to phase system construction limits the flexibility of implementation.