22.1Cross-Section Design

All architecture is shelter, all great architecture is the design of space that contains, cuddles, exalts, or stimulates the persons in that space.Philip Johnson, architect, 1906–2005

In the conceptual-design phase, the right-of-way is the first consideration as that is the boundary of where the BRT corridor will be designed. Once the boundaries of that are understood, you can start creating design assumptions to see where decisions need to be made due to space constraints.

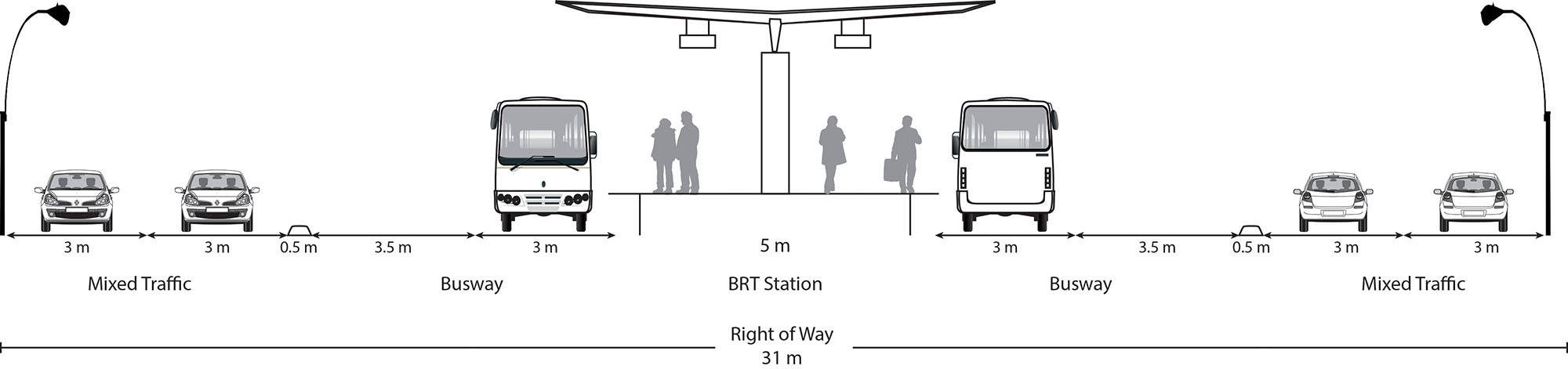

Box 22.1 Standard Widths for Conceptual Design

Busway lane: 3.5 meters

Busway passing lane: 3.5 meters

Busway lane at station: 3 meters

Station: 5 meters

Barrier/curb separator: 0.5 meter

Mixed-traffic lanes: 3 meters

The best BRT systems have used the opportunity of reconstructing the corridor for exclusive busways to invest in upgrading the environment for pedestrians and cyclists. This is partly to support sustainable transportation options, but it is also less of a cost burden to the system to have people arrive at the station by foot or bicycle than by a feeder bus. The easier it is for these customers to arrive at the stations, the more customers and the more revenue. Finally these improvements have been shown to help leverage economic development around the corridor.

Customers need sidewalks to gain access to the system, and will gravitate toward the corridor and then walk along the route to access the nearest station. A minimum sidewalk width of 2 meters unobstructed (by trees, vendors, lighting poles, street furniture) should be considered, but where moderate to high pedestrian flows are predicted the width of the sidewalk should be increased to 2.5 to 3 meters (or wider), if the road reserve width exists. Where the pedestrian flows can be predicted along a sidewalk, the level of service of the sidewalk should be evaluated to ensure that the sidewalk is wide enough to accommodate the predicted flow.

Some of the best BRT systems in the world have included bicycle infrastructure along the corridor. Bogotá is home to Latin America’s largest bicycle network, with some 376 kilometers of dedicated bike lanes. The new Orange Line BRT system in Los Angeles, the BRT corridor in Guangzhou, China, and many other new BRT corridors under development also have parallel bicycle facilities along the entire corridor.

Cyclists, like all travelers, seek the most direct and fastest way to reach their destination. If no cycling facilities are provided, the likelihood of bicyclists using the busway as a bikeway is fairly high, and very difficult to control. Finally, the inclusion of a bike lane can help mitigate the loss of a mixed-traffic lane, as some private automobile traffic could potentially shift to bicycle.

For all of these reasons, a plan to build segregated busways should also consider adding cycling facilities—this should be part of the cross-section conceptual design assumptions. The BRT Standard awards full points for bicycle lanes that are directly on the corridor, or parallel (but close) to the corridor.

The type of infrastructure depends on:

- The speed and intensity of the general traffic lanes;

- The type of cyclist activity anticipated within the corridor—i.e., recreation, commute, sport, or for student travel;

- The availability of road reserve width to accommodate bicycle lanes;

- The intensity of pedestrian traffic anticipated on the sidewalks.

The design assumptions for cycle lanes depends on the type:

- 2.0 meters for separate one-way bikeways, including space for a buffer area or separator;

- 3.0 meters for shared bikeways/sidewalks;

- 1.5 meters for marked, one-way bicycle lanes in the roadway or bike lanes;

- 1.5 meters for unmarked, one-way bicycle lanes in the roadway, indicated using signage.

If the bike lanes will be used by non-motorized three wheelers, 2.5 meters is recommended. For more detailed information see Chapter 31: Bicycle and Pedicab Integration. The BRT Standard awards more points for bike lanes that span the entirety of the corridor, and fewer points for bike lanes that exist in parts, but not all, of the system.

In the conceptual design phase a decision about the type of separation between the busway and the mixed-traffic lanes needs to be taken. Key considerations include space, enforcement needs (i.e., where enforcement is strong, a less overtly physical separation is needed).

Rouen, France, has a semipermeable barrier between the busway and the mixed-traffic lane that allows private vehicles to encroach temporarily onto the busway in case of lane obstruction. This solution assumes a corridor has available right-of-way of at least 14 meters for vehicles, plus an appropriate amount of space for pedestrians. Additional space is also required in areas with stations, which likely require at least another 3 meters of width. This solution works in places where enforcement is strong.

Where enforcement is weak and encroachment of the busway is likely, impermeable barriers may be necessary between the general traffic lanes and the busway. This is especially needed when there is only one moving traffic lane adjacent to the busway since the temptation to encroach can be significant. Guayaquil, Ecuador, has done this successfully using an impermeable barrier or a raised curb to separate the bus lane from the mixed-traffic lanes. In Nantes, France, where encroachment is less of a problem, a permeable barrier (rumble strip) separates a single mixed-traffic lane from a busway.

In places where there is snow, a buffer around the busway may be needed for snow storage after plowing.